In Paul and the Stoics (2000) Troels Engberg-Pedersen, building on major scholarly perspectives of Paul, argues for three new ways of understanding Paul’s thought and “theology”.

In Paul and the Stoics (2000) Troels Engberg-Pedersen, building on major scholarly perspectives of Paul, argues for three new ways of understanding Paul’s thought and “theology”.

1. Historical reading

Following Malherbe (Paul and the Popular Philosophers, et al), E-P insists that Paul should not be seen as “against” some Greco-Roman background, but as “being ‘ part of a shared context’: a shared Greco-Roman discourse in which he participated as a Hellenistic Jew.” For E-P this means much more than compiling a stock-take of the points where Paul’s thought compares and contrasts with its religious-historical background. E-P goes much further than Malherbe by arguing that Paul’s overall thought shares the ancient ethical traditions of moral philosophers of his day.

In brief, the present work argues for similarity of ideas between Paul and the Stoics right across the board and fundamentally questions the widespread view that [there is a] basic, intrinsic difference between the perspectives of Paul the (Hellenistic) Jew and the ethical tradition of the Greeks. (p.11)

The basic similarity between Paul and the Stoics, argues E-P, is “not just with regard to a number of particular, relatively minor topoi, but to the whole cluster of motifs that together constitute a major pattern of thought.” What does Paul share with the ethical view of his day, in particular with his contemporary Stoics? E-P argues that they both share “the idea of a ‘conversion’ or ‘call’ understood as a change in self-understanding“. More specifically, they share the idea of an ethical change as

“a move away from identification with the self as a bodily, individual being,

via an identification with something outside the self,

and to a perspective shared with and also directed towards others,

[and this perspective will then also] issue immediately in practice.”

2. The validity of Paul’s discursive arguments apart from ideological critique

E-P describes his approach to Paul as a complement of Meeks’ study in The First Urban Christians. While Meeks interprets discrete ideas of Paul and metaphors he used through the actual community practices in relation to their wider social world, E-P focuses entirely on the discursive — sequential and logically knit — ideas of Paul. These, he believes, tell their own valid story without having to be subsumed under attention to arguments about social practice.

3. The consistency of Paul’s thought

Thirdly, E-P embraces the “Paul-was-positive-about-everything-distinctly-Jewish” arguments connected with Sanders and Räisänen. But where S and R see Paul struggling, even psychologically, from letter to letter to work out a consistent argument to accommodate a godly law with the saving power of faith in Christ, E-P, on the other hand, argues that there is far more consistency than S and R realized. This consistency is brought to light when the letters are read with an ancient Stoic’s perspective.

The Paradoxical Junction

So for all of Paul’s apocalyptic and religious terminology, Troels Engberg-Pedersen’s study of Paul’s epistles has concluded that, at core, Paul expresses a message that mirrors what contemporary Stoic philosophers understood as the human situation and the processes required for this to be exalted to an ideal norm.

Paul’s Christ, for example, serves the same function as Reason or “Logos” in the Stoic philosophy of Cicero and Seneca. One’s life is ideally to be found “in Reason/Christ”, conforming one’s life to that of the nature of Reason/Christ, with one’s fleshly desires and passions mortified, and in the process being found in a new community (whose polity is from above, not of this earth) of like-minded others. Both Stoicism and Paul’s Christianity are normative. That is, both teach that one’s conduct is to be governed by clearly defined standards.

To take a trivial example, where the Stoics spoke of rationality and reason (though also identifying this with God), Paul speaks of God and Christ. Still, the claim is that it is the same basic structure that holds together Stoic ethics and Paul’s comprehensive theologizing. Only, where they set forth the structure in its transparent nakedness, Paul made use of the same structure, but in a welter of ways of speaking that were partly philosophical and partly metaphorical (though Paul himself probably considered them eminently ‘realistic’ and directly referential). (p. 47)

Of course there are differences. Paul’s communities (churches) are more every-day realities than sought-for ideals; Stoic philosophy consistently enjoins compassion for a wider circle of humanity than do Paul’s letters.

Paul and the Stoics argues that the primary differences do not touch on the common substance underlying both Stoic and Pauline views of human nature and its transformation via a higher agent. The differences very often come down to being matters of expressive metaphors and presentation styles. Paul’s apocalyptic and religious language smokescreens the fact that his thought draws on the repository of Stoic philosophy. For all of Paul’s asserted concern for a time and event that is not yet here, but nonetheless imminent, and for “the Christ event” having initiated the time towards that final event, Paul remains committed and most concerned about the here and now, in particular about the cognitive understandings, self-identities, and behaviour and conduct of individuals and communities in the here and now.

The Model

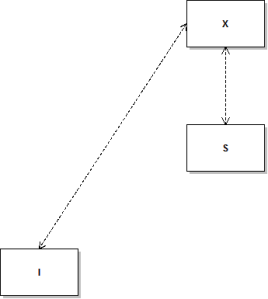

E-P uses a diagram to illustrate his model to help readers follow the common thread in both Paul’s and Stoic writings. I have drawn a much-simplified version of this:

E-P calls it the I-X-S model. Keep in mind that I have simplified E-P’s original diagram. I will also be compelled to somewhat simplify the explanation of the model.

The I box represents the individual before being converted (to either Stoicism or Christianity). This individual values and follows the basic self-centred desires, such as for food, clothing, pleasure and so on. It does not matter if this individual belongs to whatever other social groups, or even if he or she lives a life of isolation from others, the basic values of this person relate to the person’s bodily needs and interests.

The X box represents God, identified as Reason by the Stoics and with (sometimes as) Christ by Paul. When the individual (I) is “struck by” Reason/Christ (X) he attains a cognitive understanding of the nature of X, and responds with a desire to reach towards X. The individual begins to conform one’s values to those of X. This means that he comes to have an “objective” view of himself as a result of seeing himself in the same way X sees him. The individual’s desires and values now conform to those of X. The individual becomes of “one mind” with X.

The S box represents the quintessential social community. After the individual is “struck by” and reaches upward towards Reason/Christ, he or she is placed via X into this community of like-minded persons. This community is the one the individual comes to identify with, no matter what other attachments to former communities or groups remain. The individual now has the same values and objective outlook on himself and the world and all others in it. The individual now has the same concern for fellow community members as does X. He/she no longer primarily values her own interests, but the interests of all members equally. The community also reaches up towards X as it continues to seek to identify more with X and the values and mind of X.

The I box is placed lowest in the diagram to represent its “far removed from, or far below, the X” state in the cosmology. It is also placed on the left as an indicator that it is a condition that exists prior to its mutual relationship with X and being placed into the X-designated community.

Once an I is “in X” and then “in S”, one is “in” these absolutely, completely, as surely as black is black and white is white. In another sense, one is also progressing towards a fuller grasp of X and a one-ness with S.

That’s enough for one post. Will continue with some specifics in another posting soon-ish.

Continued in Christian conversion — an idea crafted by Paul from ancient philosophy