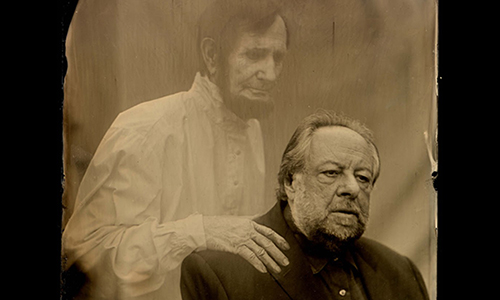

Poster from the film Deceptive Practice.

When magician Ricky Jay performs an amazing card trick, people will often ask, “How do you do that?” He always answers, “Very well, thank you.”

Such masters of prestidigitation rarely, if ever, give away their secrets. Sometimes they take their arcane methods with them to the grave, leaving even their fellow conjurers to wonder for eternity, “How did he do that?”

Of course, it isn’t supposed to be that way in scholarship. We should be able to look at a paper’s abstract and have a fairly good idea as to the author’s thesis, methods, terminology, etc. And yet, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read the works of the Memory Mavens and wondered to myself, “What are they getting at?”

Worse than that, I’m frequently left wondering how the scholar, after many pages of legerdemain, leaves us with a portrait of Jesus left on the table — which is exactly the one he predicted (and hoped) he would find. What was his method? “How did he do that?”

A New Methodology?

The Memory Mavens often spend a great deal of time expounding upon the deficiencies of the criteria approach. In Chris Keith’s Jesus Against the Scribal Elite: The Origin of the Conflict he says it “represents [an] ill-conceived historiographical method that is essentially stuck in historical positivism.” (Keith, 2014, Kindle Locations 1539-1540) He writes:

. . . I consider it irreparably broken and invalid as a historical method. The issue for the scholarly agenda now is to define a post-criteria quest for the historical Jesus. (Keith, 2014, Kindle Locations 1559-1561, emphasis mine)

As far as Keith is concerned, we can take the criteria of embarrassment, dissimilarity, coherence, and all the rest, and throw them right out the window. They aren’t just broken; they’re fundamentally flawed.

In his concluding essay to the volume, Jesus among Friends and Enemies: A Historical and Literary Introduction to Jesus in the Gospels, Keith notes with disdain that relying on criteria “mistakenly” assumes we can extract the “real” Jesus hidden behind the text. He notes that more and more scholars are abandoning this approach.

Since the criteria of authenticity are built upon this assumption, and devised as a means of separating one from the other, this abandonment problematizes the usage of criteria of authenticity. (Keith, 2011, Kindle Locations 6314-6315, emphasis mine)

I hate when things get problematized, and I’ll bet you do, too. So the best thing, clearly, would be to set them aside. Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 8: Chris Keith, Post-Criteria Scholar? (1)”