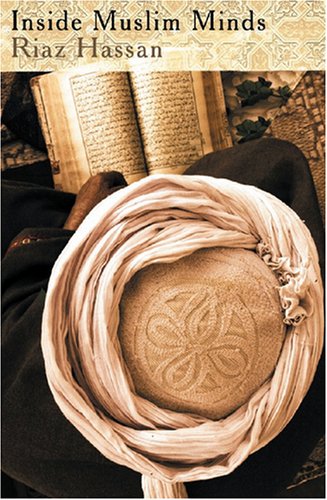

My first post covering a little of what I learned about the Muslim religion (Sharia) and its global applications did not get off to a good start. I have already posted three times on Rahim’s Muslim Secular Democracy: Voices from Within so this post is based on a key theme in the third of the works I found most useful in my attempt to understand the Muslim world, Riaz Hassan’s Inside Muslim Minds.

My first post covering a little of what I learned about the Muslim religion (Sharia) and its global applications did not get off to a good start. I have already posted three times on Rahim’s Muslim Secular Democracy: Voices from Within so this post is based on a key theme in the third of the works I found most useful in my attempt to understand the Muslim world, Riaz Hassan’s Inside Muslim Minds.

I won’t repeat the horrific news we have all heard about beheadings, stonings, amputations, honour killings though Hassan describes in some detail several of the more shocking cases of these in the pre-ISIS era, especially from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Worse, since the introduction of these laws that were supposedly intended to

protect honour, life and the fundamental rights of a citizen, as guaranteed under the constitution and to ensure peace and provide speedy justice through an independent non-discriminatory Islamic system of justice (p. 23)

the long term consequences have been the reverse. Instead of fewer accusations against blasphemy and sexual offences the numbers of incidents of these brought before the courts has only been avalanching:

In such a society as Pakistan, with its deeply embedded patriarchal beliefs and attitudes, the hudood laws in general and the law pertaining to zina (fornication and adultery) in particular have been widely and recklessly abused. In particular, they have become an instrument of oppression against women. . . .

The hudood laws and their successors have severely eroded and undermined the constitutional guarantees of life and liberty for all citizens. Instead of protecting ‘honour, life and the fundamental rights of a citizen’, these laws have become instruments of oppression.

The hudood laws, far from creating a just and equal society, have succeeded only in imprisoning half of the country’s population ‘in a web of barbaric laws and customs’. (pp, 23, 27, 28)

Developments like these do disturb more enlightened Islamic scholars:

According to some Islamic scholars, the introduction of these laws represents an ugly blot on the divine purity of Islamic doctrine. In a carefully researched book, Dr Mohammad Tufail Hashmi, a well-known Pakistani Islamic scholar, argues that, in conferring supposed ‘divine’ status on the Islamic hudd laws as well as on supporting laws laid out in the Pakistan Penal Code, the hudood ordinances violate the sanctity of the divinely ordained laws of Islam. They also convey a flawed and unworthy image of Islam to the world. In Islamic juristic tradition, punishing an innocent is a greater and more serious sin than acquitting a guilty person. According to Hashmi, the enforcement of hudood laws in Pakistan is a perversion of Islamic law and is perpetuating a warped image of Islam. (p. 28)

And the Pakistan slide into this kind of barbarism is symptomatic of what has been happening in other Muslim countries, too. Pakistan is not alone.

Of course not all Muslims approve of these sorts of laws. But as Hassan points out,

the fact that a significant proportion of Muslims at least tolerates them indicates a troubling level of moral lethargy in the collective life of contemporary Islam. (p. 35)

But let’s be fair to Mr Hyde and not overlook the undoubted humanity of his other Dr Jekyll nature:

It is also important to emphasize that the examples described above coexist with a pervasive sense of common humanity, kindness and genuine concern for the well-being of others and the under privileged in Muslim societies. (p. 35)

Having spent some time getting to know a few Muslim countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Turkey) I can certainly vouch for that side of the Muslims. Natural disasters, refugees, orphans, the poor — generosity among the ordinary Muslims wanting to alleviate suffering of those affected is often truly inspiring. Muslims I have known in Indonesia, even around the region of Solo that was until recently infamous as a hideout region for Islamic terrorists, really do have human souls, too.

Before beginning to analyze historically and empirically what accounts for the ugly side of so many Muslim countries Riaz Hassan raises the following question:

Do the laws and practices described at the beginning of this chapter negate not only the humanitarian traditions of Islam but also the essential message of the Qur’an, which enjoins believers to establish a viable social order on earth that will be just and ethically based? Only the most deluded or self-absorbed Muslims could remain unconcerned by the sheer quantity and ugliness of the incidents described earlier. The hudood and blasphemy laws of Pakistan, the seriously flawed judicial systems and the rampant oppression of women and the poor (who are the main victims of the hudood ordinances and other similar laws) cannot be attributed to an aberrational fanaticism considered marginal and unrepresentative. The evidence suggests instead a pattern of abusive practice. The Qur’an is full of warnings to Muslims that if they fail to establish justice and bear witness to truth, God owes them nothing and will replace them with other people who are more capable of honouring God by establishing justice and human equality on earth. (p. 36, my own bolding)

What has led to this state of affairs?

People do not just wake up one day and decide to commit acts of terrorism, kill in the name of ‘honour’, or behead someone for possessing an amulet—in the name of Islam. They are not naturally inclined to sanction acts by religious establishments of the state that prevent young female students from escaping a school fire, or humiliate victims of rape and injustice—in the name of Islam. Such acts take place because of social dynamics that have desensitized and deconstructed a society’s sense of moral virtue and ethics. (p. 37)

Hassan’s explanation draws most heavily upon the writings of Dr Khaled Abou El Fadl. I’ll try to do the account of Fadl and Hassan justice in the next post.