Here are all the posts I have completed so far on Russell Gmirkin’s book, Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible. You can also read an extended abstract or chapter by chapter outline by Gmirkin himself on his academia.edu page.

As you can see I have not yet begun to post anything on the final chapter of the book. And what’s worse, I can see from post #18 that I am still stuck at the same place I was over a year ago! Blame my long time love of ancient history for this situation. So when I came to the chapter covering foundation stories I found myself revisiting a raft of Greek foundation myths, their sources, and literary and thematic structures, and doing too many posts on that one point. I’ve often found myself also chasing up new data relating to historical methods that I have been discussing on Vridar quite often, and also learning about historical controversies and how the debates are conducted among classicists and ancient historians (with half a mind comparing the way such disagreements are handled in certain quarters of biblical studies). Further, I’ve spent some time following up studies not just on concrete points of similarity (e.g. a hero leaves a high culture; hero experiences a divine command; etc.), but on literary structures of the narratives themselves. I’d like to write more about those.

As you can see I have not yet begun to post anything on the final chapter of the book. And what’s worse, I can see from post #18 that I am still stuck at the same place I was over a year ago! Blame my long time love of ancient history for this situation. So when I came to the chapter covering foundation stories I found myself revisiting a raft of Greek foundation myths, their sources, and literary and thematic structures, and doing too many posts on that one point. I’ve often found myself also chasing up new data relating to historical methods that I have been discussing on Vridar quite often, and also learning about historical controversies and how the debates are conducted among classicists and ancient historians (with half a mind comparing the way such disagreements are handled in certain quarters of biblical studies). Further, I’ve spent some time following up studies not just on concrete points of similarity (e.g. a hero leaves a high culture; hero experiences a divine command; etc.), but on literary structures of the narratives themselves. I’d like to write more about those.

But no, Russell’s book also shares some of the blame. Many pages are crammed with the bare equivalent of “dot points” with referrals to end-notes (several pages away) to find follow up examples and further elaboration. For example, look at this last paragraph on page 226 (with my bolding, of course):

The foundation story proper typically included an explanation of the circumstances leading up to the launching of an expedition of colonization to a new land. According to the typical sequence of events, negative circumstances at home, such as overpopulation,37 famine,38 plague,39 natural disaster,40 economic subjection,41 stasis,42 exile,43 defeat at war,44 or escape from impending conquest45 and enslavement46 prompted a decision to found a new colony. In the Jewish foundation story by Hecataeus of Abdera in ca. 315 b c e , overpopulation was the reason why the Egyptians sent colonists to settle Babylon, Argos, Colchis and Judea (Diodorus Siculus, Library 1.28.1-3 [colonization accounts]; 29.5 [reason for colonies]). In Manetho’s story of ca. 285 b c e , Jerusalem and Judea were first settled by the Hyksos, foreign kings who had enslaved Egypt, who were eventually expelled by the Egyptians because of a plague caused by their impious foreign practices (Josephus, Apion 1.75-91, 228-51; cf. Gmirkin 2006: 170-213). In the biblical Exodus story of ca. 270 b c e , Manetho’s story was turned on its head: plagues fell on the impious Egyptians for enslaving the children of Israel and to convince Pharaoh to release them so they could worship Yahweh in the wilderness (cf. Gmirkin 2006: 187-91, 212-13). The Exodus as an escape from slavery was in keeping with Hellenistic foundation story motifs and was a central recurring theme in biblical accounts. Egyptian enslavement of its populace and the use of slave labor for the creation of Egyptian monuments such as the pyramids were also proverbial (Herodotus, Histories 2.124; Aristotle, Politics 5.1313b). The miraculous deliverance of the children of Israel was a narrative element unique to the biblical . . . .

That is not a quick read for anyone who wants to know the detail, the examples, in order to know how well the argument really works when examined more closely. I would much rather the end-notes had been printed on the same page as the main text. Yes, that would sometimes mean only a few lines of main text on a page where many follow up references and discussions had to be added, but for me that would have made a much easier read. I’m also greedy enough to want more than line references in the sources that I have to go away to look up. Adding quotations would add to the length of the book, of course, but it would have made it much easier to feel one has the complete picture, not just direction signage to lead one to locate the pieces of the picture for oneself.

But I can’t complain about the book lacking detail or the means to follow up the many topics addressed.

I have these past few weeks been following up additional reading (from the end-notes — and then more readings as I follow up the second and third order citations), piecing together the various sources for other foundation myths I have not covered on Vridar yet. But enough is enough. I will post more on those myths and their structural similarities to many of the Biblical stories at another time. Next post must begin with a look at the final chapter.

Did I say enough is enough on the foundation stories?

But what about the differences, the unique features in the Bible stories?

Allow me one more particularly interesting point Gmirkin offers with respect to the unique features of the Bible’s foundation stories (pp. 230-31). Fortunately for you readers this passage only has one end-note to follow up and I have copied it right next to the main paragraph so you don’t have to turn pages or click links to find it! 🙂

91 The tradition history approach of Rolf Rendtorff and the European school hypothesized the independent formation of the various units composing the narratives of Genesis- Joshua, which were thought to have been unified only at the last stage of redaction; cf. Rendtorff 1990. But these narrative units (aside from the primordial history in Genesis 1-11) may now be seen as essential story elements within a typical foundation story: the ancestral land promises, the departure or exodus, the wanderings, the receiving of the law, the conquest and settlement of the land. The individual units are best understood as having been composed with overall narrative scheme in mind. The explanation of these units as expected components of a foundation story appears to weigh decisively against the redaction critical model.

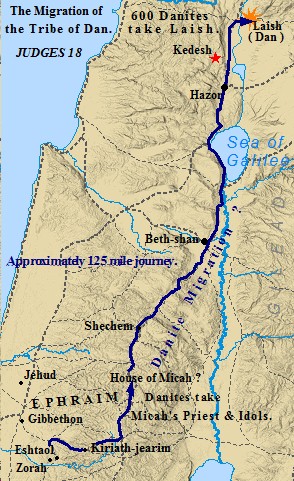

As can be seen from the earlier comparisons, the biblical narratives about the patriarchal promises and the later Exodus, Sojourn and Conquest form a connected unity that closely conforms to the Greek literary genre of ktisis or foundation story.91 As with many foundation stories, the biblical account has its own distinctive features. Although some Greek colonizing expeditions began as an escape from slavery, and although some Greek lawgivers claimed divine inspiration, both the biblical Exodus and the giving of the law at Sinai were accompanied by divine signs and wonders not typical of Greek accounts. The authors of Deuteronomy appear to have been keenly aware of these innovations in Israel’s foundation story. Deut. 4.32-34 claimed that one could make inquiries and not find another nation to the ends of the earth and the dawn of time that had heard the voice of God speaking directly out of the fire (an allusion to the Sinai theophany of Ex. 19-20, 24) or was taken by signs, wonders and a mighty hand from out of the midst of another nation (cf. Ex. 34.10). This statement displays consciousness of a literary genre dealing with the origins of nations – namely the foundation story, which was known only in the Greek world – and that the Israelite foundation story was unique in Yahweh’s direct role as deliverer and lawgiver.

So here’s a list of posts directly discussing Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible and others (mostly indented) related to the theme of the book. Continue reading “Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible – Post #32”

Like this:

Like Loading...