One of the purposes of Vridar is to share what its authors have found of interest in biblical scholarship that unfortunately tends not to be easily accessible to the wider lay public. (Of course, our interests extend into political, science and other topics, too. For further background see the authors’ profiles and the explanations linked at the what is vridar page.)

Some people describe Vridar as “a mythicist blog” despite the fact that one of its authors, Tim, is an agnostic on the question and yours truly regularly points out that the evidence available to historians combined with valid historical methodology (as practised in history departments that have nothing to do with biblical studies) may not even allow us to address the question. The best the historian can do is seek to account for the evidence we do have for earliest Christianity.

There are some exceptional works, however, that do follow sound methods and draw upon an in-depth knowledge of the sources and the wider scholarship to argue strong cases that Christian origins are best explained with a Jesus figure who had little grounding in history, and this blog has been a vehicle to share some of those arguments, usually by means of guest-posts. If a hypothesized historical Jesus turns out to be the most economical explanation for that evidence, then that’s fine. We are atheists but neither of us has any hostility to religion per se (we respect the beliefs and journeys of others) and I don’t see what difference it makes to any atheist whether Jesus existed or not.

Unfortunately, in some of our discussions of biblical scholarship both Tim and I have found what we believe are serious flaws in logic of argument and even a misuse or misleading “quote-mining” of sources. In response, a number of biblical scholars have expressed a less than professional response towards this blog’s authors and what they wrote. Some years back, in heated discussions, I myself occasionally responded in kind but I apologized and those days are now all long-gone history. Fortunately, a number of respected scholars have contacted us to express appreciation for what we are trying to do here at Vridar and that has been very encouraging.

(For what it’s worth, this blog has also often been the target of very hostile attacks from some of the supporters of less-than-scholarly arguments for a “mythical Jesus”.)

So with that little bit of background behind us, I now have the opportunity to address Larry Hurtado’s blog post, Why the “Mythical Jesus” Claim Has No Traction with Scholars.

Fallacy of the prevalent proof

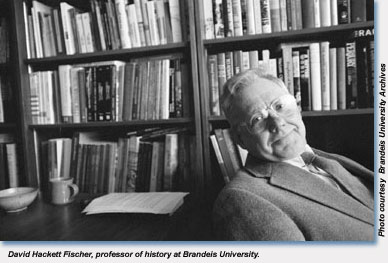

A fact which every historian knows is not inherently more accurate than a fact which every schoolboy knows. Nevertheless, the fallacy of the prevalent proof commonly takes this form — deference to the historiographical majority. It rarely appears in the form of an explicit deference to popular opinion. But implicitly, popular opinion exerts its power too. A book much bigger than this one could be crowded with examples. — David Hacket Fischer,

Historians’ Fallacies. See

earlier post for details.

Hurtado begins:

The overwhelming body of scholars, in New Testament, Christian Origins, Ancient History, Ancient Judaism, Roman-era Religion, Archaeology/History of Roman Judea, and a good many related fields as well, hold that there was a first-century Jewish man known as Jesus of Nazareth, that he engaged in an itinerant preaching/prophetic activity in Galilee, that he drew to himself a band of close followers, and that he was executed by the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate.

That is a sweeping statement and I believe it to be misleading for the following reasons.

I doubt that the “overwhelming body of scholars” in any of the fields listed, apart from New Testament and Christian Origins, has ever addressed the question of the historicity of Jesus. Certainly, I can accept that probably most people in the West, not only scholars, who have discussed ancient times have at some time heard or made mention of Jesus as a “historical marker”. The life of Jesus is public knowledge, after all. And public knowledge is culturally (not “academically”) transmitted. I suspect that “the overwhelming body of scholars” in all fields who have ever mentioned Jesus in some context have never investigated the academic or scholarly arguments for his existence. That doesn’t make them unscholarly. It simply puts them within their cultural context. I also suspect that for “the overwhelming” majority of those scholars, the question of the historicity of Jesus made no meaningful difference to the point they were expressing.

Hurtado in his opening statement is appealing to what historian David Hackett Fisher labelled the fallacy of the prevalent proof.

These same scholars typically recognize also that very quickly after Jesus’ execution there arose among Jesus’ followers the strong conviction that God (the Jewish deity) had raised Jesus from death (based on claims that some of them had seen the risen Jesus). These followers also claimed that God had exalted Jesus to heavenly glory as the validated Messiah, the unique “Son of God,” and “Lord” to whom all creation was now to give obeisance.[i] Whatever they make of these claims, scholars tend to grant that they were made, and were the basis for pretty much all else that followed in the origins of what became Christianity.

Here we have a continuation of the above fallacy. Yes, what Hurtado describes is what most people (not only scholars) in the Christian West have probably heard at some time and taken for granted as the “Christian story”. Again, what Hurtado is referring to here is a process of cultural transmission. Very few of “these same scholars” have ever studied the question of historicity. We all repeat cultural “memes” the same way we quote lines of Shakespeare.

After 250 years of critical investigation

The “mythical Jesus” view doesn’t have any traction among the overwhelming number of scholars working in these fields, whether they be declared Christians, Jewish, atheists, or undeclared as to their personal stance. Advocates of the “mythical Jesus” may dismiss this statement, but it ought to count for something if, after some 250 years of critical investigation of the historical figure of Jesus and of Christian Origins, and the due consideration of “mythical Jesus” claims over the last century or more, this spectrum of scholars have judged them unpersuasive (to put it mildly).

This statement is a common but misleading characterization of the history of the debate. I think it is fair to say that in fact scholars have not at all spent the past 250 years investigating the question of the historical existence of Jesus. Their studies have, on the contrary, assumed the existence of Jesus and sought to resolve questions about that historical figure’s nature, career, teachings, thoughts, impact, etc. Forty years ago the academic Dennis Nineham even described the importance of the historical foundations of the story of Jesus to meet the needs of theological and biblical scholars. (See earlier posts on his book, The Use and Abuse of History.)

The number of biblical scholars who have published works dedicated to a refutation of the “Christ Myth” theory are very few and, though often cited, appear to have been little read. According to Larry Hurtado’s own discussions, it appears that he has only read one such work, one dated 1938, that I think few others have ever heard of. See “It is absurd to suggest . . . . “: Professor Hurtado’s stock anti-mythicist. (He may have read other such criticisms, and more recent and thorough ones, of which I am unaware.)

The fact is that the few scholars who have historically “come out” to argue that Jesus did not have a historical existence, beginning with Bruno Bauer, have been ostracized and soon ignored by the fields of theology and biblical studies.

In normal academic debate an author is given a right to a reply to criticisms of his work. I have yet to see a mainstream biblical scholar actually address (as distinct from ridicule or insult) any of the responses of Christ myth supporters to those works that are supposed to have debunked mythicism, such as those of Shirley Jackson Case, Maurice Goguel and now Bart Ehrman. One gets the impression that many scholars are content to accept that scholars like Ehrman have “taken care” of the arguments and the matter can be safely left at that. In fact, most replies to the works of Case, Ehrman and others are demonstrations that they have failed to address the core arguments despite their claims to the contrary.

Sometimes an offensive manner is used as an excuse to avoid engaging in serious debate or responses to criticisms, which is a shame because I have seen rudeness and other lapses in professionalism on both sides. Mainstream scholars would, I think, be more persuasive among their target audience if they took the initiative in seizing the high ground of a civil tone and academic rigour in all related discussions. Unfortunately, several academics are even on record as saying that they fear to show normal standards of respect and courtesy with mythicist arguments for fear that they would be interpreted as giving the view a “respectability it does not deserve.” That sounds to me like a reliance upon attempted persuasion by means of condescension, abuse and bullying.

The reasons are . . .

Continue reading “Reply to Larry Hurtado: “Why the “Mythical Jesus” Claim Has No Traction with Scholars””

Like this:

Like Loading...

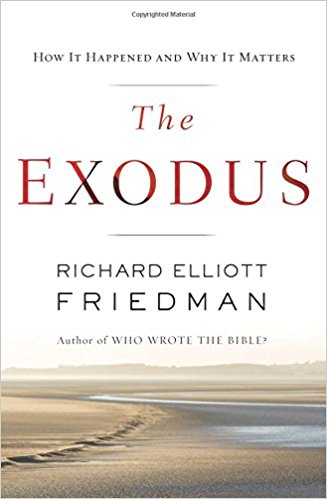

A month ago I posted my view of a scholar’s claim to be able to extract “nuggets” of historical events from a textual analysis of the biblical narrative of the Exodus: Can we extract history from fiction?

A month ago I posted my view of a scholar’s claim to be able to extract “nuggets” of historical events from a textual analysis of the biblical narrative of the Exodus: Can we extract history from fiction?