As I was recently tossing out old papers that had accumulated over past decades I was amused to come across this old “gem” of mine. I posted it back in 1996 to a discussion forum for ex-members of an old cult I had once been a member of. It has no pretence at scholarly presentation. It is simply an off-the-cuff reflection on what I had been reading at the time about how the New Testament came into being. There are details in it that I would not fully stand by today but “for old time’s sake” here is what I wrote for a select audience 28 years ago.

(The reference to the Waldensians and Cathars had particular relevance to us cult and ex-cult members of the day — we curiously believed we were their heirs in some sense.)

|

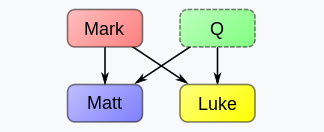

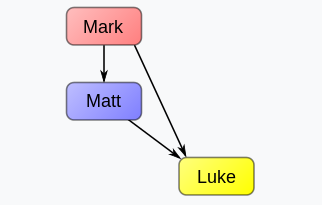

THE TRUE TALE OF HOW AN EAGLE, A LION, A MAN, AND A LOT OF BULL ENTERED THE CHURCH Following is a lengthy brief summary of why most Christians today can claim Mr Irenaeus, a bishop who lived about 130-200, as the reason for their New Testament Bibles. He was the one who began the invention of the New Testament. He did this in order to have a tool to preserve the power of the catholic bishops whenever they were confronted with nuisances who wanted to base their beliefs directly on the original teachings of Christ instead of relying on the traditions and authority of those bishops. By mid second century, Christians were a pretty diverse lot without any concept of an “inspired” New Testament canon. The sabbath-observing portion of the Palestinian church accepted only the writings of Matthew; some docetist believers only used Mark; Valentinus’ followers accepted only the gospel of John; and others who followed Paul to his logical conclusions sought to uncover the original text of Luke and rejected all else as contradictory to what Christ and Paul taught three to four generations earlier. (Note that archaeology indicates that the average life-span of a lower-class Palestinian in the first century was about 30 years — a point that puts “late eyewitness” arguments in an interesting context.) And there were other gospels, too, as well as copies of the “Teachings of Christ”. Moreover, the reason a believer tended to follow only one gospel in opposition to the others was that that believer was convinced that the others contradicted his authority, and/or was a late forgery. Out of all this confusion (or richly rewarding diversity for the more secure?) arose a powerful threat to the power of many established bishops. His name was Marcion, a brilliant thinker who rejected “human church tradition” as his authority and who sought instead to rely only on apostolic authority. He saw that the church had corrupted some of the original texts of Paul and Luke (modern scholars in this age when knowledge has increased have come to the same conclusions) and believed only what he read in their original texts, and not the traditions that the bishops said he should believe. Many followed Marcion and his arguments against the traditions of the catholic bishops. He became a threat to the power of these bishops. Then the bishops found a defender and saviour of their power, position and traditions in Irenaeus. (Some who read this will by now be jumping up and down wanting to argue that Marcion was a gnostic heretic. As you wish, but my point is that he was a powerful influence in the second century church and many believers were persuaded that he was truer to the original teachings of Jesus than the traditions that had developed among the bishop-ruled church. Recall that his enemies were the fathers of those who were the enemies of the Waldensians, and the Waldensians were also accused of gnosticism.) Irenaeus did not have the same incisive and logically detailed mind as Marcion, but he did have faith and a determination to preserve and extend the authority and traditions of the bishops over believers. Disregarding the contradictions among the various gospels he stridently argued that Matthew, Mark, Luke and John should ALL be accepted as authoritative, basically because of his assertion that the traditions that he personally accepted about them were true. (He was not interested in historical or textual research as Marcion was, and many of those traditions have since been shown to have very little merit indeed.) Of course by blanketly asserting the authority of these four, Irenaeus was also partly opening the way for most dissidents (who believed in at least one of them) to return to the fold. And to those who did not accept the authority of the bishops, he “proved” his point by powerfully demonstrating that they coincided with the four winds and corners of the earth. But wait, there was more! Each could, with a little ingenuity, be fitted with a nicely matching mythological head — eagle, lion, man and bull. (Later generations had a lot of trouble with Irenaeus’s taste in hybrids, though, and kept swapping these heads around to try them out on different gospel torsos from the ones to which Mr I. had attached them.) So there! This was the catholic bishop’s answer to those hard questions about contradictions in the texts and evidence of late and spurious authorship and editing. Marcion had been seeking to rely exclusively on the original teachings of one apostle. Irenaeus saw the danger of this to the authority of the bishops and used his episcopal authority to declare non-apostolic authors as authoritative, too. (e.g. Mark and the late revised edition of Luke). This showed that the apostles were not so special after all, and that the bishop-led church (not the apostles) had the right to decide what traditions, writings and doctrines people should believe. No more Marcionites or Ebionites or others who snubbed their noses at the tradition and authority of the bishops in preference for their exclusively “apostolic” authority! And that is why today we still all believe that those four gospels alone are authoritative. (It was quite some time after Irenaeus that they actually introduced the idea that they were “inspired” or “God-breathed”. And later on, after the dust had settled, the more imaginative theologians could be given the job of making up a whole lot of stuff so that their blatant inconsistencies — and any tell-tale signs of spurious authorship and later unauthorized editing — could be “harmonized” away.) Irenaeus carried the flag for the authority of the catholic bishops and introduced the idea that the church would eventually have to finalize a New Testament canon if the bishop’s power were to be maintained against smart-alecs who sought to uncover and rely exclusively on the original words of Christ and/or any of the apostles. In future generations, Christians could claim that there was an undisputed tradition in the church that these four gospels were penned by two genuine, original apostles and two genuine off-siders of another two apostles. Well, there was such a tradition at least from the second century, I guess, IF one accepts that the incipient Catholic Church of the third century was the only church worth considering, and if they further acknowledge the authority and teachings of the bishops of that Church. But even if that is the case, then one has to wonder why Irenaeus did not include a whole lot of other writings that we now have in our New Testament — if indeed there was such an indisputable tradition — not to mention why other texts he believed were authoritative were subsequently dropped and lost altogether. |