Theologians draw out spiritual lessons from the tale of God sending his Son in the flesh, performing miracles and teaching truths incomprehensible to most, and then dying and returning once again to heaven so he can be with many more followers here and now who do understand and appreciate his fleshly advent. The same theologians even explain history in terms of this theological drama. Followers of Jesus were so shocked by the unexpected demise of their hero on the cross that they feverishly set about fabricating this spiritually meaningful tale to compensate for their disillusionment by restoring among themselves a new faith and hope for a future life.

The possibility that that spiritually meaningful story might have been the original source of the tale of the historical advent of Jesus seems not to occur to them. (No, I am not saying the story was fabricated overnight ex nihilo. All stories and genres have their antecedents, and such antecedents to the Gospel story and genre are a lot more in evidence in the record than we are conditioned to quickly acknowledge.)

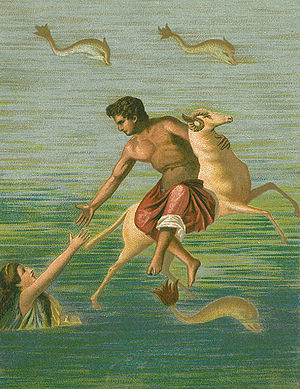

But let’s do a little comparative religious study to see if another ancient cult can shed any light on the question of Jesus’ historicity. Continue reading “The mythical meaning of gods (Dionysus, Jesus) being given historical settings”

April DeConick in

April DeConick in

Continuing from the

Continuing from the