This is the second post in my review of Nathanael Vette’s Writing With Scripture: Scripturalized Narrative in the Gospel of Mark. The series is being archived at Vette: Writing With Scripture. For a richer understanding of the creative literary world that gave rise to our Gospel I highly recommend reading these reviews of Vette’s work alongside an earlier series on Literary Imagination in Jewish Antiquity by Eva Mroczek: those posts are archived at Mroczek: Literary Imagination in Jewish Antiquity. While Mroczek explores the ways in which authors understood existing “scriptures” and the ways they felt justified in “rewriting” them, Nathanael Vette [NV] takes us into the close-up view of how authors of the era pieced together new stories from elements of existing ones. (Vette twice favourably cites the views of Eva Mroczek.)

Did the author of the Gospel of Mark create events in the life of Jesus by selecting and combining in new ways various passages and motifs from the Jewish Scriptures?

That Mark used the Jewish scriptures in this way depends in large part on whether this practice can be identified in other works from the period. If it can be shown across a diverse group of texts that the Jewish scriptures were regularly used to compose new narrative, then it would be appropriate to speak of scripturalized narrative as a stylistic feature of Second Temple literature. (NV, 29)

And again,

That Mark composed new stories out of scriptural elements will thus appear all the more likely if the practice can be observed elsewhere, and it is to this question the study will now turn. (NV, 31)

Here I will cover just one of the five Second Temple works that NV studies.

It makes sense to begin with having a clear idea on how to identify a “scriptural allusion or echo” in a passage, keeping in mind that the study is about more than explicitly interpreted passages and stories from (Jewish) Scripture. NV relies upon Dale Allison’s list of criteria as set out in The New Moses. Instead of repeating them here, here is the link to where I set them out, with discussion, and in comparison with other criteria for the same purpose: 3 criteria lists for literary borrowing.

NV begins with Pseudo-Philo’s Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum, or rather with three episodes from the LAB (its standard abbreviation). NV does not discuss the date of this work (Biblical Antiquities) but it is widely accepted as belonging to the Second Temple period. If you want to know why the LAB is dated to the first century see D. J. Harrington’s explanation in Old Testament Pseudepigrapha Volume 2 at archive.org, p. 299; further, a more recent discussion appears in the German language thesis of Eckart Reinmuth, Pseudo-Philo und Lukas, also at archive.org, pp 17-26. (Both Harrington and Reinmuth are referenced in NV’s work although Reinmuth has unfortunately been overlooked from the author index.)

We cannot pinpoint precise details of how Scriptures were used in the narrative constructions of LAB since the surviving texts are Latin translations that do no more than leave hints of Hebrew and Greek source texts. Nonetheless, the narratives we have clearly indicate two levels of scriptural sourcing:

- a narrative in the LAB can be based primarily on a story we read in, say, the Pentateuch: that is, a retelling of the career of Israel from the time of the twelve spies being sent into Canaan through Korah’s rebellion and Balaam’s prophecies and concluding with the death of Moses;

- that same narrative can be supplemented by events and speeches from other, usually comparable, episodes: so sayings and incidents from Genesis, Joshua and 1 Chronicles can be introduced into the main narrative to enrich it with new detail.

Hence, we read in LAB 17:

Then was the lineage of the priests of God declared by the choosing of a tribe, and it was said unto Moses: Take throughout every tribe one rod and put them in the tabernacle, and then shall the rod of him to whomsoever my glory shall speak, flourish, and I will take away the murmuring from my people. 2. And Moses did so and set 12 rods, and the rod of Aaron came out, and put forth blossom and yielded seed of almonds. 3. And this likeness which was born there was like unto the work which Israel wrought while he was in Mesopotamia with Laban the Syrian, when he took rods of almond, and put them at the gathering of waters, and the cattle came to drink and were divided among the peeled rods, and brought forth [kids] white and speckled and parti-coloured.

That’s quite straightforward. But what is of interest to us is when this author (who was once mistaken for Philo) creates new episodes from the raw materials of Scripture.

NV itemizes several examples. One that he does not elaborate on did catch my attention because it stood out from the others as the creation not only of a new event but of a new character.

The figure of Aod the Midianite magician (LAB 34) is based on Moses’ description of the false prophet (Deut. 13:1-4) among other passages. (NV, 37)

I followed up the references and present here a table to demonstrate how this new person is moulded from Scripture.

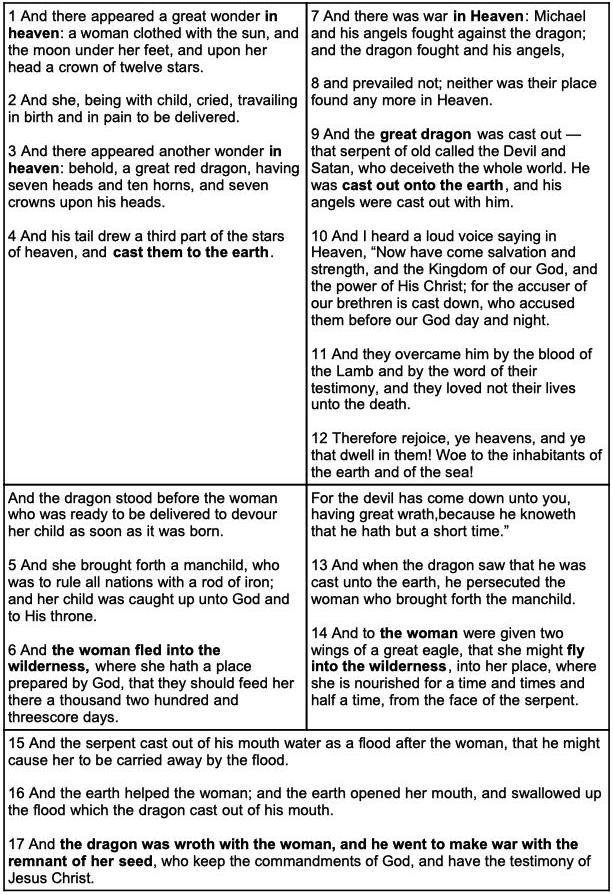

| Deuteronomy 13:1-4 | LAB 34 |

| If a prophet, or one who foretells by dreams, appears among you and announces to you a sign or wonder, and if the sign or wonder spoken of takes place, and the prophet says, “Let us follow other gods” (gods you have not known) “and let us worship them,” you must not listen to the words of that prophet or dreamer. The Lord your God is testing you to find out whether you love him with all your heart and with all your soul. It is the Lord your God you must follow, and him you must revere. Keep his commands and obey him; serve him and hold fast to him. | And in that time there arose a certain Aod from the sanctuaries of Midian, and this man was a magician, and he said to Israel, “Why do you pay attention to your Law? Come, I will show you something other than your Law.” And the people said, “What will you show us that our Law does not have?” And he said to the people, “Have you ever seen the sun by night?” And they said, “No.” And he said, “Whenever you wish, I will show it to you in order that you may know that our gods have power and do not deceive those who serve them.” And they said, “Show it. “And he went away and worked with his magic tricks and gave orders to the angels who were in charge of magicians, for he had been sacrificing to them for a long time. Because in that time before they were condemned, magic was revealed by angels and they would have destroyed the age without measure; and because they had transgressed, it happened that the angels did not have the power; and when they were judged, then the power was not given over to others. And they do these things by means of those men, the magicians who minister to men, until the age without measure comes. And then by the art of magic he showed to the people the sun by night. And the people were amazed and said, “Behold how much the gods of the Midianites can do, and we did not know it.” And God wished to test if Israel would remain in its wicked deeds, and he let them be, and their work was successful. And the people of Israel were deceived and began to serve the gods of the Midianites. And God said, “I will deliver them into the hands of the Midianites, because they have been deceived by them.” And he delivered them into their hands, and the Midianites began to reduce Israel to slavery. |

Okay, maybe Aod doesn’t earn top marks for creative ingenuity but it is a sign of a new individual being “born”, is it not? Perhaps you will be more impressed with an angelic figure named Nathaniel when we come to the discussion of Jair below.

The Rescue of Abram from the Fiery Furnace

Continue reading “Creating New Stories from Scripture — a review of Writing with Scripture, part 2”