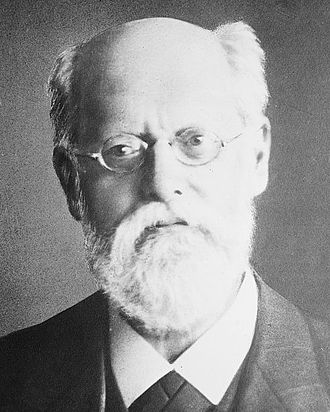

Alvar Ellegård (November 12, 1919 – February 8, 2008) was a Swedish scholar and linguist. He was professor of English at the University of Gothenburg, and a member of the academic board of the Swedish National Encyclopedia.

. . . He also became known outside the field for his work on the conflict between religious dogma and science, and for his promotion of the Jesus myth theory, the idea that Jesus did not exist as an historical figure. His books about religion and science include Darwin and the General Reader (1958), The Myth of Jesus (1992), and Jesus: One Hundred Years Before Christ. A Study in Creative Mythology (1999). (Source: Wikipedia)

He wrote “Theologians as historians”, now available online, published originally in Scandia the year he died, 2008. The article addresses arguments commonly advanced by theologians against the Christ Myth idea but it also has much to say about scholarly resistance to even being willing to debate such a thesis. I quote a few passages here from that section of his article. (Headings and bolding are my own.)

Theologians are not living up to their responsibility

It is fair to say that most present-day theologians also accept that large parts of the Gospel stories are, if not fictional, at least not to be taken at face value as historical accounts. On the other hand, no theologian seems to be able to bring himself to admit that the question of the historicity of Jesus must be judged to be an open one.

It appears to me that the theologians are not living up to their responsibility as scholars when they refuse to discuss the possibility that even the existence of the Jesus of the Gospels can be legitimately called into question. Instead, they tend to dismiss as cranks those who doubt that the Jesus of the Gospels ever existed.

Dogmatism is characteristic . . . under cover of mystifying language

It is natural that different historians come to different conclusions on questions for which our sources are late, scanty or biassed. Thus most historians, though skeptical about king Arthur, avoid being dogmatic about him, whatever the stand they are taking. But dogmatism is characteristic of the theologians’ view of matters which are held to guarantee the historicity of Jesus.

That dogmatism, however, is too often concealed under a cover of mystifying language. An instance in point is quoted by Burton L. Mack, who quotes Helmut Koester, characterizing him, very properly, as “a New Testament scholar highly regarded for his critical acumen” (Mack 1990, p. 25). Koester writes:

“The resurrection and the appearances of Jesus are best explained as a catalyst which prompted reactions that resulted in the missionary activity and founding of the churches, but also in the crystallization of the tradition about Jesus and his ministry. But most of all, the resurrection changed sorrow and grief … into joy, creativity and faith. Though the resurrection revealed nothing new, it nonetheless made everything new for the first Christian believers” (Koester 19822, p. 84-86).

Mack comments drily: