If the book of Revelation is to be dated to the time of Hadrian (specifically to the late 120s or early 130s) how might the “four horsemen of the apocalypse” be understood?

If the book of Revelation is to be dated to the time of Hadrian (specifically to the late 120s or early 130s) how might the “four horsemen of the apocalypse” be understood?

Some commentaries propose that the white horse represents the preaching of the gospel. The difficulty with this interpretation is that the first rider emerges from the same place as the other horsemen who bring calamities to the world. Should we not expect the white horseman also to be a harbinger of death and suffering?

Revelation 6:1 And I saw when the Lamb opened one of the seven seals, and I heard one of the four living creatures saying as with a voice of thunder, Come. 2 And I saw, and behold, a white horse, and he that sat thereon had a bow; and there was given unto him a crown: and he came forth conquering, and to conquer.

Here is how Thomas Witulski interprets the passage as a prelude to the time of Hadrian. The details are from Die vier ,apokalyptischen Reiter‘ Apk 6,1-8.

A white horse

There is a considerable amount of evidence in ancient Greco-Roman literature linking “white horses” not only with military conquest, imperial power and rulership but also with extending the prestige acquired from those conquests to the level of equality with the divine, especially with the chief god of the Greco-Roman pantheon, Zeus/Jupiter.

The Roman historian Livy wrote at a time when the Republic of Rome was in crisis and a new age of “emperors” was dawning. Notice the nervous alarm with which he addresses the idea of a past Roman hero using white horses in his Triumphal march through Rome:

The return of Camillus drew greater crowds than had ever been seen on such an occasion in the past, people of all ranks in society pouring through the city gates to meet him; and the official celebration of his Triumph left in its splendour all previous ones in the shade. Riding into Rome in a chariot drawn by white horses he was the cynosure of every eye – and indeed in doing so he was felt to be guilty of a certain anti-republican arrogance, and even of impiety. Might there not be sin, people wondered, in giving a man those dazzling steeds and thus making him equal with Jupiter or the God of the Sun? It was this disquieting thought that rendered the celebration, for all its magnificence, not wholly acceptable. — Livy, V, 23

A later historian, Suetonius, wrote of the advent of Augustus to the world:

On the day Augustus was born, when the conspiracy of Catiline was being discussed in the senate house and Octavius stayed away until late because his wife was in labour, Publius Nigidius, hearing why he was delayed, when informed of the hour of the birth, asserted (as is generally known) that the master of the world was born. When Octavius, who was leading an army through remote regions of Thrace, sought guidance concerning his son at some barbarian rituals in the grove of Father Liber, the same prediction was made by the priests, for so great a flame had leapt up when they poured wine on the altar, that it passed beyond the peak of the temple roof and right up to the sky, a portent which had only previously occurred when Alexander the Great offered sacrifice at that altar. And on the very next night thereafter, he dreamed he saw his son of greater than mortal size with a thunderbolt and sceptre and emblems of Jupiter Best and Greatest and a radiate crown, on a chariot decorated with laurel drawn by twelve horses of astonishing whiteness. — Suetonius, Augustus, 94

By the time of Julius Caesar it was evidently the custom to allow white horses for a conqueror’s Triumph:

For they had voted that sacrifices should be offered for his [Julius Caesar’s] victory during forty days, and had granted him permission to ride, in the triumph already voted him, in a chariot drawn by white horses. — Cassius Dio, Roman History, XLIII, 14,3

Greek and Roman historians described a focus on white horses in Persian royal processions in a similar way:

Then came ten of the sacred horses, known as Nisaean, in magnificent harness, followed by the holy chariot of Zeus drawn by eight white horses, with a charioteer on foot behind him holding the reins – for no mortal man may mount into that chariot’s seat. — Herodotus, Histories, 7, 40

Next after the bulls came horses, a sacrifice for the Sun ; and after them came a chariot sacred to Zeus; it was drawn by white horses with a yoke of gold and wreathed with garlands ; and next, for the Sun, a chariot drawn by white horses and wreathed with garlands like the other. After that came a third chariot with horses covered with purple trappings, and behind it followed men carrying fire on a great altar. – Xenophon, Cyropedia, VIII, 3, 12

Then came the chariot consecrated to Jupiter, drawn by white horses, followed by a horse of extraordinary size, which the Persians called ‘the Sun’s horse’. — Rufus, History of Alexander, 3, 11

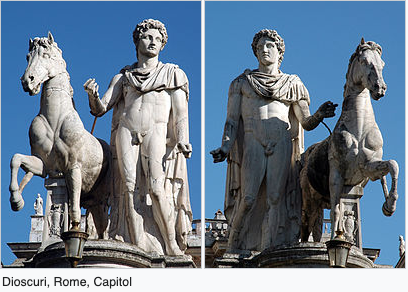

Nor let’s overlook the famed white horses of Castor and Pollux, the sons of Zeus: https://www.theoi.com/Ther/HippoiDioskourioi.html

Nor let’s overlook the famed white horses of Castor and Pollux, the sons of Zeus: https://www.theoi.com/Ther/HippoiDioskourioi.html

Then did the Sons of Zeus, my brethren twain,

Flashing on white steeds come to war with thee. — Euripides, Iphigeneia at Aulis, 1153-1154

We read of other instances where white horses are associated with raw imperial power without any pronounced religious connotation:

. . . in the middle is Rhesos the king, son of Eïoneus. His are the most beautiful horses I have beheld and the most magnificent; they are whiter than snow, they run like the wind . . . Homer, Iliad, X, 435-37

Hard by, his white steeds to his Thracian car

Are tethered : clear they gleam athwart the dark

As gleams the white wing of a river-swan. — Euripides, Rhesus, 616-618[King Turnus] called for his horses and joyfully watched their restive excitement. These horses had been given to Pilumnus by Orithyia herself – a proud possession, for they could outmatch snow in their white brilliance and the winds in their speed. — Virgil, Aeneid, XII, 82-84