We have been looking at some accounts among ancient historians of gods and heroes appearing among eyewitnesses and acting in history. Did the ancient historians and biographers who wrote of those events believe they were true? What of other people who heard of those stories? Did they believe them?

In my review posts of How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths by M. David Litwa I have pointed out a number of times that historians of ancient times generally distanced themselves from reports of the appearances of gods or miraculous events: they did so with terms such as “it is said that . . .”, “a rumour spread that . . .”, etc. This distancing technique stands in contrast with fictional stories where the authors write from the all-knowing stance and simply say that the appearances of gods and miracles did happen. Ditto for the gospels. (There are a few exceptions that I have pointed out, the most notable one being Suetonius’s account of Augustus Caesar. Omens are also often written about as if they really happened but these are usually accounts of naturally occurring events — birds fighting, an unexpected storm — that are interpreted as divine signs.)

As for the historians and biographers themselves, we can assume they had an above average education so their reservations when they came to writing about the supernatural or mythical are not surprising. We would expect the less educated on the whole to be less cautious when they were exposed to the myths that were at the heart of their piety. Classicist Jorge Bravo of the University of Maryland has published the evidence for the two different approaches to myths, or more specifically towards myths about Greek heroes, “mortal figures who were thought to possess some residual power after death.” To clarify the meaning of hero:

But what is a hero? In modern usage the word carries with it a positive valorization, describing anyone who accomplishes great feats and inspires admiration and emulation.

For the ancient Greeks, at least by the Classical period, the designation applied to a broad spectrum of figures that included not just the well-known warriors of Homeric epic and other early legends but also more shadowy figures, about whom, to judge by our ancient sources, the Greeks themselves knew only the slightest details. . . .

What does unite the heterogeneous lot of Greek heroes is first a belief that they were, in fact, mortals, not gods; they lived and died, whether in the remote past or in recent times. Moreover, although now dead, they are believed to have a power over the living, and as a consequence they are worshiped alongside the gods.

(Bravo, Recovering the Past, 11)

Another distancing technique of the educated

As has been pointed out in previous posts . . .

The authors [ancient historians and biographers] are prone to distance themselves from pronouncing on the authenticity of the claimed epiphanies, and the accounts allow for different opinions about the events that transpired. One indicator of this authorial mediation is the frequent use of the term φάσμα [=phasma: apparition, phantom . . . ]. . . .

. . . the use of the term φάσμα in the ancient literary accounts of heroic epiphany qualifies the experience that the author is relating to the reader, leaving open to doubt the veracity of the claim.

(Bravo, Heroic Epiphanies, 67-68)

Another distancing technique of the educated

I have pointed to other distancing phrases like “It is said that…” Here Bravo identifies the use of φάσμα (phasma) as another.

Some examples. One in Pausanias, speaking of Aristomenes, the leader of the Messenian revolt against Sparta, in the seventh century BCE.

After waiting only for the wound to heal, he was making an attack by night on Sparta itself, but was deterred by the appearance of Helen and of the Dioscuri [φασμάτων Ἑλένης καὶ Διοσκούρων] (Pausanias, 1.16.9)

The Dioscuri, of course, are the Twins, Castor and Pollux, our better known Gemini.

Another in Herodotus of a moment in the Battle of Salamis (480 BCE):

The story is also told that the phantom of a woman [φάσμα σφι γυναικὸς] appearedto them, who cried commands loud enough for all the Hellenic fleet to hear, reproaching them first with, “Men possessed, how long will you still be backing water? (Herodotus, 8.84)

Plutarch records that many believed Theseus appeared at the Battle of Marathon (490 BCE):

In after times, however, the Athenians were moved to honor Theseus as a demigod, especially by the fact that many of those who fought at Marathon against the Medes thought they saw an apparition of Theseus [φάσμα Θησέως] in arms rushing on in front of them against the Barbarians. (Plutarch, Theseus, 35.5)

Why might φάσμα be a distancing word?

In light of the dichotomy between image and reality entertained in Greek thought from the fifth century on, the use of the term φάσμα calls into question the veracity of the superhuman event. It opens the door to alternative explanations for the events, for instance the possibility that military leaders staged events to inspire courage and confidence.

(Bravo, Heroic Epiphanies, 68. Bolded highlighting is my own in all quotations)

Fake epiphanies? They want to believe!

Here are some examples of people faking appearances of gods and heroes, but what is most significant for us is that did so knowing that at least a significant number of others would be fooled, would really believe. The first listed here is non-committal, saying only that “some” thought the events were tricks orchestrated by the leaders.

The Thebans accordingly decorated this monument before the battle. Furthermore, reports were brought to them from the city that all the temples were opening of themselves, and that the priestesses said that the gods revealed victory. And the messengers reported that from the Heracleium [=Temple of Heracles] the arms also had disappeared, indicating that Heracles had gone forth to the battle. Some, to be sure, say that all these things were but devices of the leaders.

(Xenophon, Hellenica, 6.4.7 — the battle described took place in 371 BCE)

I find that example of particular interest because it matches one of the signs listed by Josephus before the fall of Jerusalem. See the fourth sign in Miracles with Multiple Jewish and Roman Eyewitnesses: I had wondered why people would consider the self-opening of temple doors to be a good omen and the passage in Xenophon suggests that the people would have interpreted it as evidence that the god/s had gone forth to fight their enemies.

The next two extracts refer to the Messenian revolt against Sparta in the seventh century BCE.

The Lacedaemonians [=Spartans] were keeping a feast of the Dioscuri in camp and had turned to drinking and sports after the midday meal, when Gonippus and Panormus appeared to them, riding on the finest horses and dressed in white tunics and scarlet cloaks, with caps on their heads and spears in their hands. When the Lacedaemonians saw them they bowed down and prayed, thinking that the Dioscuri themselves had come to their sacrifice.

When once they had come among them, the youths rode right through them, striking with their spears, and when many had been killed, returned to Andania, having outraged the sacrifice to the Dioscuri.

(Pausanias, 4.27.2-3)

Another account of the same:

On the day of the festival, when the Lacedaemonians [=Spartans] make a public sacrifice to the Dioscuri, Aristomenes the Messenian and a friend mounted on two white horses, and put golden stars on their heads. As soon as night came on, they appeared at a little distance from the Lacedaemonians, who with their wives and children were celebrating the festival on the plain outside the city. The Lacedaemonians superstitiously believed that they were the Dioscuri, and indulged in drinking and revelling even more freely. Meanwhile, the two supposed deities, alighting from their horses, advanced against them with sword in hand. After leaving many of them dead on the spot, they remounted their horses, and made their escape.

(Polyaenus, Stratagems of War, 2.31.4)

I’ll add one more, this one from Herodotus who makes no effort to hide his embarrassment.

The Greeks have never been simpletons; for centuries past they have been distinguished from other nations by superior wits; and of all Greeks the Athenians are allowed to be the most intelligent: yet it was at the Athenians’ expense that this ridiculous trick was played. In the village of Paeania there was a handsome woman called Phye, nearly six feet tall, whom they fitted out in a suit of armour and mounted in a chariot; then, after getting her to pose in the most striking attitude, they drove into Athens, where messengers who had preceded them were already, according to their instructions, talking to the people and urging them to welcome Pisistratus back, because the goddess Athene herself had shown him extraordinary honour and was bringing him home to her own Acropolis. They spread this nonsense all over the town, and it was not long before rumour reached the outlying villages that Athene was bringing Pisistratus back, and both villagers and townsfolk, convinced that the woman Phye was indeed the goddess, offered her their prayers and received Pisistratus with open arms.

(Herodotus, Histories, 1.60)

It should be evident that a good number of ancient Greeks were willing to believe that gods and heroes continue to act in history and their own day and are not figures confined exclusively to some remote “heroic age”. More sophisticated authors might express some reservations but they did not deny that many others were “true believers”.

Jorge Bravo devotes the second part of his article to the non-literary evidence. He heads it

II. Heroic Ephiphany in Votive Iconography

and begins,

While authors may interject a note of uncertainty in their accounts of epiphany, for many ancient Greeks the experiences were undeniable. Such popular beliefs fueled religious responses, including the dedication of offerings. A passage in Plato’s Laws alludes to this dynamic. Plato has his Legislator promote a law to curb what he regards as foolish popular religious practices (909e-910a):

… It is customary for all women especially, and for sick folk everywhere, and those in peril or in distress (whatever the nature of the distress), and conversely for those who have had a slice of good fortune, to dedicate whatever happens to be at hand at the moment, and to vow sacrifices and promise the founding of shrines to gods and demi-gods and children of gods; and through terrors caused by waking visions (εν τε φάσμασιν) or by dreams, and in like manner as they recall many visions and try to provide remedies for each of them, they are wont to found altars and shrines … (Loeb).

This documents how individuals frequently responded to visions and other experiences with dedications and the foundations of shrines. Indeed the evidence is strong that the sheer number of offerings could at times present problems for sanctuaries.

In the iconography of votive dedications, accordingly, one should find direct testimony of the kinds of private beliefs that could be called into question by authors.

(Bravo, Heroic Epiphanies, 68 f)

Anyone interested in Christian origins will surely pause over the above quotation. It suggests that one might expect to find records of dedications at the tomb of Jesus or at sites in Galilee where Jesus had made a splash with a speech or miracle of some kind, or at a site near Caesarea Philippi where Peter first acknowledged Jesus to be the Christ, or at the Mount of Olives and Gethsemane, or even the Jordan where John baptized, and pilgrimages to the wilderness where he was tempted or where he persuaded by some mysterious means for crowds of thousands to be fed. (Those who respond with some quip to the effect that ancient Jews were not like that, not like the Greeks, would have to explain why it is recorded that Jesus said the Pharisees did just that sort of thing with the tombs of the prophets.) But let’s move on.

As you go to the portico which they call painted, because of its pictures, there is a bronze statue of Hermes of the Market-place, and near it a gate. . . . At the end of the painting are those who fought at Marathon . . . . Here is also a portrait of the hero Marathon, after whom the plain is named, of Theseus represented as coming up from the under-world, of Athena and of Heracles. The Marathonians, according to their own account, were the first to regard Heracles as a god. . . .

(Pausanias, 15.1.1, 3)

The best-known example is Polygnotus’ painting of the Battle of Marathon that Pausanias describes seeing in the Stoa Poikile in Athens (Paus. 1. 15. 3). Pausanias informs us that several heroes were represented taking part in the battle, namely Theseus, Heracles, the eponymous hero Marathon, and the farmer hero Echetlus.

(Bravo, HE, 69)

That last name, Echetlus, we met earlier in an earlier post, though with an archaic spelling. See Greek Gods and Heroes with Multiple Historical Eyewitnesses (Echetlaeus = he of the plough-tail).

The hero-god Asclepius was the healer who had a vital place for many worshipers who looked to him for recovery but there were several other healing gods, too. Or I say hero, or both, because heroes were originally mortals who had acquired divine powers and remained active among believers after their passing from the mortal realm. The god-hero and the worshiper interacted with one another.

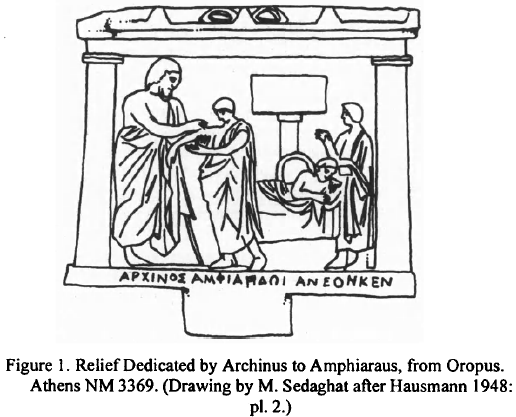

Among private votive offerings, the epiphany of the hero finds explicit representation in dedications made in the context of healing. Numerous reliefs exist that represent the epiphany of a healing hero (and here I would include the god-hero Asclepius) on a thank-offering. An interesting example is a relief of the first half of the fourth century B.C.E. dedicated by Archinus to the hero Amphiaraus at Oropus (Figure 1). This relief illustrates a double epiphany: to the left, the epiphany of Amphiaraus as Archinus dreamed it, and to the right, the epiphany of a snake, which could be observed licking Archinus’ wounded shoulder as he slept in the enkoimeterion. Votives to healing heroes that represent the hero’s actions thus make explicit the reciprocity between the worshipper and the hero. It is this relationship that can be detected more generally in votive representations of heroes.

(Bravo, HE, 69 f)

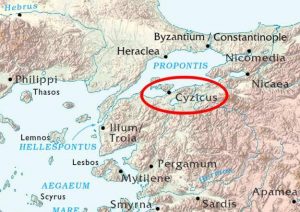

Bravo further points to one engraving depicting Heracles standing over and about to slay a Gaul. This image was dedicated to the general of Cyzicus in 278-77 BCE. This is the only visual representation of a hero fighting human opponents known to Bravo.

Bravo further points to one engraving depicting Heracles standing over and about to slay a Gaul. This image was dedicated to the general of Cyzicus in 278-77 BCE. This is the only visual representation of a hero fighting human opponents known to Bravo.

the relief visibly expresses Heracles’ potential to appear and lend aid to the people of Cyzicus.

(Bravo, 70)

Bravo discusses and illustrates several other votive offerings given in thanks for a god-hero’s intervention in the life of a devotee. Some of these heroes are represented as snakes (the snake was “a manifestation of the hero’s presence) and others as horses (“the horse signals the hero’s arrival on the scene, his readiness to take action.”)

The third part of Bravo’s essay is about celebrating a meal with the divine hero:

III. The Banqueting Hero: Epiphany in Cult?

Here are Jorge Bravo’s thoughts:

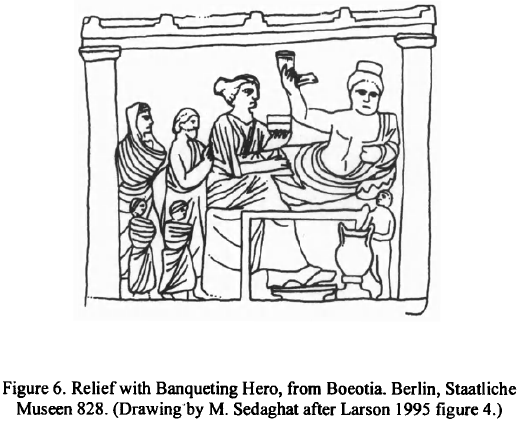

. . . I now wish to consider another common class of votive representation, the representation of the hero reclining at banquet (Figure 6). Briefly, I would like to entertain the possibility that this category of representation evokes an idea of heroic epiphany from a cult context: the epiphany of the hero in the cult practice of xenia [= guest-friendship; hospitality]. The motif of the hero reclining at banquet is known . . . dating from the late Archaic period on . . . . The scene usually consists of the hero reclining on a couch (kline) with a table (trapeza) set before him. The hero often holds a drinking cup or phiale. . . .

. . . Because early scholarship associated the reliefs with the cult of the dead, the scene was interpreted as the deceased enjoying the pleasures of his lifetime, or as a banquet being enjoyed in the afterlife. As Dentzer established, however, the scene is primarily used for the representation of heroes through the Classical period, and only later does the scene become used more frequently in a funerary context. . . .

. . . it is used to designate a range of practices in which a god or hero is invited to partake of a human meal. It is a special practice to be distinguished from the normal procedure of sacrifice, in which bones and fat are burned on the altar. Significant in light of the banqueting hero iconography is the fact that the rite of xenia involves setting out a trapeza and a kline for the divinity that is being hosted.

To what extent did the Greeks regard the ritual practice of xenia as an instance of divine epiphany? A scholiast describes the gods invited to theoxenia as των έπιδημούντων, “the ones who are visiting,” suggesting the idea of temporary presence (Schol. Pind. 01. 3, inscr.). Louise Bruit has suggested that the reason Apollo and Dionysus are most associated with theoxenia is that they are gods of epiphany, with frequent comings and goings. In regard to heroes, support for the association is found in representations of the Dioscuri appearing on their horses over a kline (Figure 7). Since rites of xenia for the Dioscuri are well attested in various Greek cities, scenes such as this . . . likely illustrate the Dioscuri arriving to partake of ritual xenia. To the extent that the epiphany of the hero is implicated in the cult practice of xenia, then the image of the reclining hero at banquet becomes another reminder of the hero’s power to reveal himself.

(Bravo, HE, 73 ff)

Am I alone in being reminded of the gospels’ depiction of the Last Supper, especially as depicted in the Gospel of John? It is the fourth gospel that draws special attention to the divine hero who “tabernacles” (temporarily dwells) among his followers.

Bravo discerns a double meaning to this banquet with the divine hero. The meal (a) invites the revelation of the god-hero and (b) is often conducted to recall another moment when that divinity was revealed.

A final point about the cultic epiphany of heroes is that this instance of epiphany in turn stands in a reciprocal relationship with the epiphanies of heroes during conflict. An illustration of this is the account of how the Locrians of South Italy transported the Dioscuri from Sparta so that they could help in the conflict with Croton (Diod. Sic. 8. 32). The Locrians set up a kline for the Dioscuri on their ship, implying that the ritual formalism of xenia was employed as a prelude to the intervention of the twin heroes.

In other episodes of heroic intervention, rites of xenia are offered afterward to honor the hero’s aid. An example is recorded in the inscribed hymn of Isyllus from Epidaurus (IG IV2.1 128). When the Spartans learned from Isyllus of Asclepius’ intention to save Sparta from Philip, they responded with a decree that Asclepius should be called Soter and welcomed into the city with rites of xenia.

Finally, there is the ploy of Jason of Pherae described by Polyaenus (Strat. 6. 1. 3). . . . Jason told his wealthy mother that the Dioscuri were his symmachoi, and that he had promised them xenia in exchange for victory in a recent battle. His mother devoutly furnished Jason with fine couches, vessels, and tableware of precious metals in order to receive the Dioscuri . . . . All these examples illustrate how the concept of epiphany can play a double role with respect to xenia. Not only might epiphany be involved in the rite itself, but also the rite is often conducted in relation to another occasion of epiphany.

(Bravo, HE, 75)

That sounds to me as though a meal with the divine hero, a mortal who acquired divinity, revealed to the banqueters the divine identity of their guest and was additionally a ritual to be repeated so that with each re-enactment that epiphany would not only be recalled but also invite the divinity to participate once again in the meal with mortals.

How far are we from the ritual of the Last Supper in Christianity?

Greco-Roman historians and biographers might express some scepticism, but they bear witness to a popular belief that is further supported by extra-textual evidence:

Whereas the literary accounts often approach the claims of epiphany with a judicious neutrality or even skepticism, in votive iconography one finds a more unmediated expression of the popular beliefs about heroes. (Bravo, HE, 76)

If we read sophisticated literature expressing some distancing, some doubt, about miracles and the immediate presence of gods and heroes, we must conclude on the basis of non-literary evidence that these writings support the view that belief in the immediate and historically recent appearance and activity of divine beings, including those who had once been mere human flesh.

Bravo, Jorge. 2009. “Recovering the Past: The Origins of Greek Heroes and Hero Cult.” In Heroes: Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece, edited by Sabine Albersmeier, 10–29. Baltimore: Walters Art Museum.

https://www.academia.edu/4154478/_Recovering_the_Past_The_Origins_of_Greek_Heroes_and_Hero_Cult_in_Heroes_Mortals_and_Myths_in_Ancient_Greece_Sabine_Albersmeier_ed._Baltimore_2009_10-29.

Bravo, Jorge. 2004. “Heroic Epiphanies: Narrative, Visual, and Cultic Contexts.” Illinois Classical Studies 29: 63–84.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23065341

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

One thought on “Ancient Belief that Divinities Appeared on Earth in the Present and Historical Past — (with half a glance at Christian origins)”