I have now returned to Australia from a regular overseas extended family visit, still somewhat sore from the accident I suffered over there, and in transit have been resisting the temptation to post easy “fillers” like more of the interesting differences encountered in Thailand or another response to an old McGrath post . . . hence the hiatus of the last few days. What has been on my mind, though, is some sort of extension to the previous post . . . Finally I settled on Mark 1:38 as the verse for the day. Jesus sneaked out of the house while it was still pre-dawn dark to find an isolated spot to pray. Eventually he was found by his disciples who complained that everyone had been looking for him. Jesus replied,

. . . . “Let us go somewhere else–to the nearby villages–so I can preach there also. That is why I have come.”

Such a mundane set of words. Nothing special…? But if we pause to think for a moment about that last sentence, “That is why I came”, — what was in the author’s (or, if you prefer, the mind of Jesus) when those words were expressed?

“Why I came”.

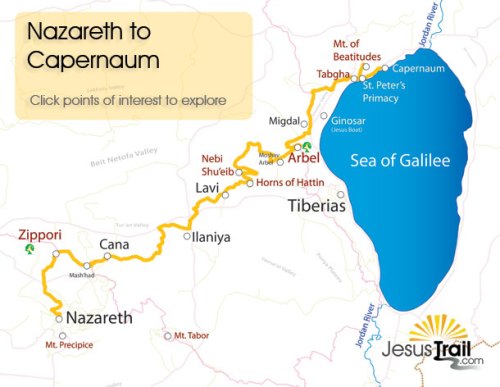

Am I reading too much (or too little) into the words when I wonder why he did not say, “That is why I have come back here” or even “that is why I came here”? Hadn’t Jesus grown up in Nazareth, Galilee? I read on one site that there is a twisty turny road from Nazareth to Capernaum (where Jesus was found praying) that extends around 40 miles:

But Jesus did not say “This is why I have come here (to Capernaum, or even to Galilee)” but “This is why I have come (ἐξῆλθον).” Luke changed what he read in Mark’s gospel to the more passive, “This is why I have been sent (ἀπεστάλην).” Mark’s Jesus did not say he was sent for a reason. Mark’s Jesus said he came forth for a certain reason.

And Mark’s Jesus does not appear to be telling his disciples that he came to Capernaum or to Galilee, but that he “came forth” . . . that is somehow more open-ended, more universalist, more existentialist — it is the reason Jesus came to . . . dare we say, to earth? Or at least to the lands where Judeans (or maybe only Galileans) were to be found?

Some readers may wonder what on earth I am getting at. The Gospel of Mark is widely accepted as the earliest of the written gospels and it is also widely understood to present the most “human-like” of the Jesus figures when we compare the Jesus in the other gospels.

But here in this simple sentence Jesus is depicted as saying that he came ….he came for a purpose. He was not “born” for a purpose. Or at least that’s not what he said.

Our minds have to go back to the beginning of the gospel. Where did Jesus come from?

John the Baptist was baptizing away and saying that someone greater than he was going to appear on the scene, then we are told that Jesus came to be baptized.

Now here it gets a bit complex and no doubt many readers will think I am overstepping “the mark” (pun not intended). Our text says Jesus came “from Nazareth”. I don’t believe that was what “Mark” wrote at all. I am convinced that “from Nazareth” are a copyists addition to the text. If you can bear with me and wait for me to offer reasons later, then accept my proposal that our purportedly earliest written gospel bluntly said that Jesus came . . . to be baptized. He came from nowhere. Thus said (or sort of implied) the text.

He simply came to be baptized. The narrative tells us nothing about his background or even who this Jesus character was. We are so familiar with the story and with far more than the story as told in this gospel that it is easy for us not even to notice how little (or even exactly what) Mark actually says.

Then when we come to Jesus’ being found alone with his God in Mark 1:38 he reminds us that we have not yet been told who this Jesus character is or where he has come from. (A comment by Martin anticipated this post.) Everything we have read so far has “only” told us that everyone (person or demon) who encounters him is over-awed by his authority. Everyone falls over backwards or drops their families and livelihoods or travels many miles merely on coming in contact with or simply hearing about his power of authority.

“For this reason I came forth” is not a quotidian remark about why he decided one day to leave Nazareth and visit Capernaum. It is a pointer to Jesus having come from heaven.

But that pointer is not likely to be noticed if we have our heads filled with the Gospels of Matthew and Luke before we read the Gospel of Mark.

. . . o 0 o . . .

Mark 1:9

At that time Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan.

That is the only time, the only verse, in the Gospel of Mark in which “Nazareth” appears. Elsewhere Jesus is called “the Nazorean” which cannot easily be derived from Nazareth. A person from Nazareth would be a “Nazarethite” or (obviously) the Greek/Aramaic equivalent.

For some detail I quote a comment by Ian Hutchesson in a Crosstalk discussion forum from some time back:

2578 Re: Galilean synagogues (Side issue)

Ian Hutchesson

Sep 22, 1998

I have been following the Galilean discussion with interest and feel that

you are all doing a fine job without me. (-:I’d just like to comment on a passing exchange between Bob and Mahlon, as it

deals with a very old thread in which I have been involved.Bob said:

>> And here’s another interesting question: If both

>> Nazareth and Capernaum are associated with Jesus, what chance is there

>> that the setting of Luke 4 has been transposed to Nazareth

>> from Capernaum?To which Mahlon replied:

>Unlikely. The parallel scene in Matt & Mark is set in Jesus’ *patrida*

>(“native place,” “hometown”) which throughout the gospels is identified

>as Nazareth (e.g., Mark 1:9, Matt 2:23, Luke 2:4, John 1:45).I think this cursory statement doesn’t take into consideration all the facts

of the matter.>Luke

>transposes & elaborates the pericope, but simply makes explicit the

>location presupposed in the parallels. Besides, Luke 4:23 makes it

>impossible to envision this scene “in the synagogue” at Capernaum.I have long argued that the mention of Nazareth in Mark 1:9 was a gloss

inserted once the Nazareth tradition had won out against Capernaum (village

of Nahum or “comfort”). It is not reflected in the parallel text in GMatt

3:13. Nazareth is not mentioned elsewhere in GMark, which sees Jesus’s home

town as Capernaum. Whereas GMatt attempts to justify the transition from the

Nazareth tradition to that of Capernaum — which was received from GMark —

in the purely Matthean material (4:13-16), no such transition is found in

GMark. The GLuke method of dealing with the conflicting traditions was to

negate the Capernaum home tradition by moving the synagogue scene from

Jesus’s home country in Mark, which can only be interpreted in the

circumstances as Capernaum, to Nazareth (nazara — GLuke only uses Nazareth

in the birth narrative).The other synoptics did not get Nazareth from GMark, and Q does not mention

Nazareth although it does talk about Capernaum. Nazareth in both GMatt and

GLuke is part of their later layers, whereas Capernaum was there when they

worked with GMark and Q.Where the mystery term “Nazarene” comes from is another matter and I have

argued for a nexus of the Judges 13:7 (“he shall be a Nazirite to God…”, a

possible source for Mt2:23) and the branch imagery from Isaiah and

Zechariah. Eisenman has thrown in the “keeper” notion “notzri ha-brit”

(keeper of the law) in his quest to connect James and Jesus to the DSS. (One

may note a large industry that has sprung up based on speculation on the

term: it’s still quite fruitful.)The Matthean scribes omitted this term (nazarEnos) in its locations in the

Marcan text, only to regain it in a later redaction in the form nazOraios —

neither of which form can be derived directly from Nazareth.The issue of Nazareth/Nazarene is far from the simple out-of-hand rejection

of Mahlon as quoted above and it has been complicated by transmission

problems, as, for example, the one surviving case of “nazarEnos” in GLuke

against two of the “nazOraios” form. We also have the problem of the two

distinct forms nazaret and nazara. While this last could conceivably supply

the gentilic “nazarene” (and this can’t be said of Nazareth), neither

provide a linguistic connection with the other apparent gentilic, nazOraios,

for which I have hazarded a tortuous transmission from Hebrew to Greek: NZYR

(Nazirite), the yod being replaced with a waw — as often seen in the DSS

–, before transliteration into Greek, supplying a root of “nazOr” +

gentilic-like “-aios”. If anyone can give a better hypothesis, I’d be happy

to hear it.I leave you with the data.

Ian

GMatt GLuke GMark

——————————————————-

1:26 nazareth

2:4 nazareth

2:39 nazareth

2:51 nazareth

2:23 nazareth,

nazOraios

1:9 nazaret

4:13 nazara

4:16 nazara

4:34 nazarEnos = 1:24 nazarEnos

18:37 nazOraios = 10:47 nazarEnos

14:67 nazarEnos

21:11 nazareth

26:71 nazOraios ? 16:6 nazarEnos

24:19 nazOraios

But the argument has other facets, as we see from Mark Goodacre’s response:

2579 Re: Galilean synagogues (Side issue)

Mark Goodacre

Sep 22, 1998On 22 Sep 98 at 16:14, Ian Hutchesson wrote:

> I’d just like to comment on a passing exchange between Bob and Mahlon,

as it

> deals with a very old thread in which I have been involved.In one of this thread’s incarnations, Ian and I had a discussion about this

matter. Since FindMail don’t seem to respond to my queries about the past

archives, I will have a look at my own archive on this and see whether there is

anything that might be worth bringing up again. In the meantime, I would like

to comment briefly on a couple of the synoptic questions here.> I have long argued that the mention of Nazareth in Mark 1:9 was a gloss

> inserted once the Nazareth tradition had won out against Capernaum

(village of

> Nahum or “comfort”). It is not reflected in the parallel text in GMatt 3:13.

> Nazareth is not mentioned elsewhere in GMark, which sees Jesus’s home

town as

> Capernaum.The lack of mention of Nazareth in Matt. 3.13 would not be, in my opinion, a

strong reason for supposing a gloss in Mark 1.9. In general I would be wary

about hypothesising a gloss on the basis of a synoptic parallel that lacks it.

The lack is not surprising in Matthew – he has specified that Nazareth was

Jesus’ home in 2.23 and will go on to detail the movements within Galilee in

4.13-16. The focus here is on the Jordan. Whereas Mark mentions Nazareth

in 1.9, Matthew does not feel it necessary because he has mentioned it already

in 2.23.> Whereas GMatt attempts to justify the transition from the Nazareth

> tradition to that of Capernaum — which was received from GMark — in the

> purely Matthean material (4:13-16), no such transition is found in GMark.Mark does not narrate the transition but mentions both Nazareth and

Capernaum.Matthew, quite reasonably, infers (probably rightly) that Jesus moved from

Nazareth to Capernaum.> The

> GLuke method of dealing with the conflicting traditions was to negate the

> Capernaum home tradition by moving the synagogue scene from Jesus’s

home

> country in Mark, which can only be interpreted in the circumstances as

> Capernaum, to Nazareth (nazara — GLuke only uses Nazareth in the birth

> narrative).Or one could say that Luke rightly inferred that by THN PATRIDA AUTOU

(Mark 6.1), meant Nazareth.>

> The other synoptics did not get Nazareth from GMark, and Q does not mention

> Nazareth although it does talk about Capernaum. Nazareth in both GMatt and

> GLuke is part of their later layers, whereas Capernaum was there when they

> worked with GMark and Q.Whether or not Nazara comes in Q is debatable. Some (Tuckett, Schuermann,

Catchpole, Robinson) read it at Q 4.16 and the International Q Project

accordingly give the text a rating of C (hesitant possibility).My own feeling is that the Q theory is in difficulty here. Either we have

to put Nazara into the category “Minor Agreement”, in which case we have a

big problem for the theory of Luke’s independence from Matthew, or we have

to put it into Q, in which case we have a big problem for the non-narrative

Q theory. The most straightforward explanation is that Luke has taken the

unique spelling here from Matthew, using Matt. 4.13 as the text to justify the

bringing forward of the Markan // Matthean rejection story. But that brings us

back to where we were at around about this time last year.Mark

——————————————-

Dr Mark Goodacre mailto:M.S.Goodacre@…

Dept. of Theology Tel: +44 (0)121 414 7512

University of Birmingham Fax: +44 (0)121 414 6866

Birmingham B15 2TT

United KingdomHomepage: http://www.bham.ac.uk/theology/goodacre

World Without Q: http://www.bham.ac.uk/theology/q

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Jesus wouldn’t have to come if his daddy had done a better job.

So many occasions of Jesus praying … to himself? I believe the trope is that Jesus sacrificed himself to himself to save us from himself.

“Let us go somewhere else–to the nearby villages–so I can preach there also. That is why I have come.”

Note the hurry that clearly seems to hang over Jesus. He is in a hurry to move from that place. Some scholars (among them, Joseph Turmel) had explained this strange hurry by Jesus in virtue of the his being without a real body. If he remained too much time in a place, the risk was that the people would have realized who was: a ghost.

The same hurry is explained by Jesus himself by the enigmatic saying:

“Foxes have dens and birds have nests, but the Son of Man has no place to lay his head.”

Foes and birds have a body. Jesus was without body hence he can’t place it nowhere.

I believe Frank Zindler argues for Mark’s Nazareth being an interpolation.

Any suggestions as to when “Nazareth” was added? Before Matthew or when whoever brought the NT together needed to iron out the worst inconsistencies and embarrassments?

It appears to me that Matthew is the inventor of the Nazareth provenance of Jesus. (He has to explain its origin.) And given the Gospel of Matthew’s popularity it would makes sense for the Mark’s reference to Nazareth to have been slipped in after Matthew’s account was well known.

I doubt that those bringing the gospels together into a canon were worried about inconsistencies. If they had been they would have done a far more serious job or rewriting them, and then they’d probably end up with a harmony of the four. The inconsistencies didn’t worry them. Where we have some passages from one gospel finding their way into another it is more likely a case of a copyist hearing in his head the more familiar phrase from a gospel he knew well and letting it slip into his copy of another gospel.

Inconsistencies were basically “taken care of” by the order of the gospels. By placing Matthew first a reader would be led to interpret the othes through Matthew’s story; and John would be interpreted through the synoptics.

Perhaps it was too late for major regerings by then. All the anti-marcionite groups wanted their gospel accepted, so the best that could be done was some minor ‘corrections’. I’m thinking also of the recent evidence that Martha was added to GJohn late to minimise the role of Mary Magdalene. Similarly the tendency to separate Mary ‘of Bethany’ from the Magdalene. Personally I similarly suspect that Lazarus was not so originally named, but the name was carried over from GLuke to diminish the Beloved Disciple.

Such tweaks seem within the realm of the possible along with the more subtle choices of order (GMatt first, epistles last, but introduced by Acts) and perhaps attribution.

Maybe Mark’s, “have come”, is a vestigial carry-over of 1 Peter’s reference to a coming:

“[T]he prophets who prophesied of the grace that would come to you made careful searches and inquiries, seeking to know what person or time the Spirit of Christ within them was indicating…”

Also, “Though you have not seen him, you love him.” Where “you” refers to people dispersed from places like Mark’s Capernaum.

Neil’s “from where?” question is also posed by an ancient critic regarding John the Baptist. In his Commentary on John (2.24/29 ff), Origen writes : “He who is sent is sent from somewhere to somewhere. .from what place was John sent, and where to? The ‘where to?’ is quite clear…”

Taking his cue from the quotation at the beginning of Mark (“behold I send my angelos before thy face”), Origen suggests that John was an ’embodied’ angel, “sent either from heaven or from paradise or from some other quarter to this place on the earth”. As his evidence for angels walking the earth in human form, he doesn’t cite OT texts, but quotes extensively “a secret book of the Hebrews”, the Prayer of Joseph.

Origen was likely correct to read ‘angelos’ in Mark as ‘angel’ ,not ‘messenger’ (the sense only in archaizing literary Greek by this time). Mk 1.1, ‘euangellion’ possibly means ‘angelic message’; there are certainly ‘ministering angels’ at Mk 1.13.

In short, there is a contextual argument from the opening of the gospel for Neil’s ‘man from heaven’ reading of 1.38…

Buckley: Your comment seems useful.

Further complicating possibilities include possible early confusions about Jesus’ possible temporary adoption of the Oath of a “Nazarite” or Nazarene. Which, if misunderstood, could have lead to the myth of Jesus coming from Nazareth.

In that oath one abstains from wine, sacrifices a goat, and is considered “separated” from other people. As a holy or almost a divine being.

“’That is why I came’, — what was in the author’s (or, if you prefer, the mind of Jesus) when those words were expressed?”

If–as I believe–the Gospel of Mark was a record/transcript/narratization of a performed play, then the audience would have seen the Jesus actor enter the stage. This line is part of the exposition of the character, adding to the characterization already shown in the Temptation scene.

In 1911, John M. Robertson “The Gospel Mystery-Play” (Pagan Christs 2.1.15) https://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/cv/pch/pch42.htm, shows how the Passion has many features of a staged play. I think that the same literary style and behavior of the characters in the pre-Passion part of GMark also points to it having been performed onstage, with the same set of conventions and audience expectations.

We can READ. The great bulk of the Gospels’ audience were just that – hearers. Some sounds/pronunciations don’t exist in other languages. I suspect the “Nazareth” thing results from mishearing something from that kind of reason. Just as Caiaphas and Cephas seem to be the same name heard differently. All kinds of things are going to go wrong when what is heard is put to parchment across languages.

“Euangellion” is used of Augustus. That “Good Message” had nothing of disembodied spirits about it! Imperial usage is hardly archaising. that is probably why the term was used – to trump and trans-value imperial propaganda. Something greater than Caesar was here. Origen is nearly two centuries later and what you can say about his context doesn’t necessarily apply to G.Mk.

Jesus appears at the Jordan opposite Jerusalem,which is a good ways further than Nazareth to Capernaum. That compounds the problem. In one of the Christianities that were retconned as heresy Jesus does just what you imply, Neil. He simply appears by the Jordan and the river backs up for him a la Joshua. The myth had developed: it no longer took place in the firmament, as in Paul, but Jesus was still blatently NOT mortal.

Mark brings his Jesus even further down to Earth but his is still a story dripping in magic and unreality. I don’t know how anyone can think G.Mk has a human Jesus in it: hardly anyone or anything in this story behaves or happens realistically and hardly anything of significance happens that isn’t basted in the supernatural. We don’t notice because the story is so familiar.

I have to agree with Danila, it looks like something performed for an audience in some fashion. Recall that the origin of all drama is sacred performance. So many things happen where there is no one to report them or the witnesses are said not to have reported them. How does the author know these things? Goddidit wont do! 🙂