The two earlier posts on The Lord’s Prayer:

Let this be my third and final post on the Lord’s Prayer. I return to the article by Michael Goulder with which I began these posts.

Our Father

I suppose by now it seems the most natural thing in the world to start the prayer with this address but it need not have been so. I suppose it could have begun, “Dear God”, “Great Lord”, “Creator of Heaven and Earth”, “Oh Ineffable One”, etc. But we have “Our Father”.

An explanation can be found in the writings that pre-dated the gospels. We learn there that addressing God as Father appears to have been widespread in Paul’s day:

Because you are his sons, God sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, the Spirit who calls out, “Abba, Father.” (Galatians 4:6)

The Spirit you received does not make you slaves, so that you live in fear again; rather, the Spirit you received brought about your adoption to sonship. And by him we cry, “Abba, Father.”(Romans 8:15)

The Gospel of Mark, the first gospel to be written (according to most studies today), carries over this custom when we find there Jesus himself praying, Abba, Father:

Going a little farther, he fell to the ground and prayed that if possible the hour might pass from him. “Abba, Father . . . “ (Mark 14:36)

Abba is the Aramaic for father, as we know. The word fell out of use, however, over time, so we see both the Gospels of Matthew and Luke dropping it and relying solely on the Greek word for father. So in Matthew’s and Luke’s copying of Mark’s scene above they drop Abba:

Going a little farther, he fell with his face to the ground and prayed, “My Father . . . “

He went away a second time and prayed, “My Father . . . “ (Matthew 26:39, 42)

Luke is even more truncated and omits the possessive pronoun:

He withdrew about a stone’s throw beyond them, knelt down and prayed, “Father, . . . “ (Luke 22:41 f)

So it is no great surprise to see Matthew’s Lord’s Prayer beginning with Our Father and Luke’s with Father.

Our Father in Heaven

Once again we begin with the earliest of the gospels, that of Mark, and a major source for both the gospels of Matthew and Luke. There we find only one time in which Jesus explicitly taught his disciples how to pray. It comes just after the disciples express amazement that Jesus’ curse on the fig tree really worked:

“Have faith in God,” Jesus answered. “Truly I tell you, if anyone says to this mountain, ‘Go, throw yourself into the sea,’ and does not doubt in their heart but believes that what they say will happen, it will be done for them. Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask for in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. And when you stand praying, if you hold anything against anyone, forgive them, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins.” (Mark 11:22-25)

That lesson on prayer in Mark (the only lesson on prayer in Matthew’s and Luke’s source) “coincidentally” introduces a major thought in the later Lord’s Prayer, the need to forgive sins of others so God will forgive us. It’s the main point of Jesus’ lesson on prayer in the Gospel of Mark and it is stressed in the Gospel of Matthew by added commentary at the end of the prayer as we shall see.

The point here, though, is that it is surely evident that the above Marcan passage was in the mind of the author of Matthew’s gospel, and there in Matthew’s source we find the same phrase, Father in heaven, as is used to introduce Matthew’s Prayer.

As we have seen in the previous post that Luke had already identified the Father he was talking about as being in heaven only 22 verses earlier so, in accord with his tendency to avoid repetition, he omits “in heaven” in his own version of the Prayer.

Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors

Refer again to Mark 11:22-25 quoted above. Again, keep in mind that this passage is the earliest narrative we have of Jesus teaching his disciples how to pray and it is used as a source for both Matthew and Luke.

Coupled with “Father in heaven” is the command “if you hold anything against anyone, forgive them, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins.”

Matthew repeated this lesson from Mark at the end of his Lord’s Prayer. It was the primary message in Mark and Matthew repeats its point after having Jesus just tell them to pray for forgiveness as they forgive others:

For if you forgive other people when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive others their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins. (Matthew 6:14 f)

Matthew was the pioneer of the Lord’s Prayer itself and he let Mark’s wording control his own thought. To reword Mark’s indirect instruction on how to pray into a direct speech prayer, it would have turned out like “Father, forgive us our sins as we forgive our sins”. That hardly made sense. But this was only a minor pause for Matthew because his favourite word for sin was “debt” — a metaphor that Goulder says was “deep in Aramaic thought”. He repeated it in the parable of the Unmerciful Servant:

21 Then Peter came to Jesus and asked, “Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?”

22 Jesus answered, “I tell you, not seven times, but seventy-seven times.

. . .

32 “Then the master called the servant in. ‘You wicked servant,’ he said, ‘I canceled all that debt of yours because you begged me to. 33 Shouldn’t you have had mercy on your fellow servant just as I had on you?’ 34 In anger his master handed him over to the jailers to be tortured, until he should pay back all he owed.35 “This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother or sister from your heart.” (Matthew 18)

No problem, then, for Matthew to convert Mark’s Jesus’ words to an eloquent expression by substituting debt for sin. Instead of

“Father, forgive us our sins as we forgive our sins”

he wrote

“Father, forgive us our debts as we have forgiven our debtors”

Luke chose to follow the original source here because we may well imagine from the number of times he elsewhere uses the direct word for sin instead of Matthew’s debts. His wording is not as concise as Matthew’s but it is more direct:

Forgive us our sins, for we also forgive everyone who sins against us.

Your Will Be Done

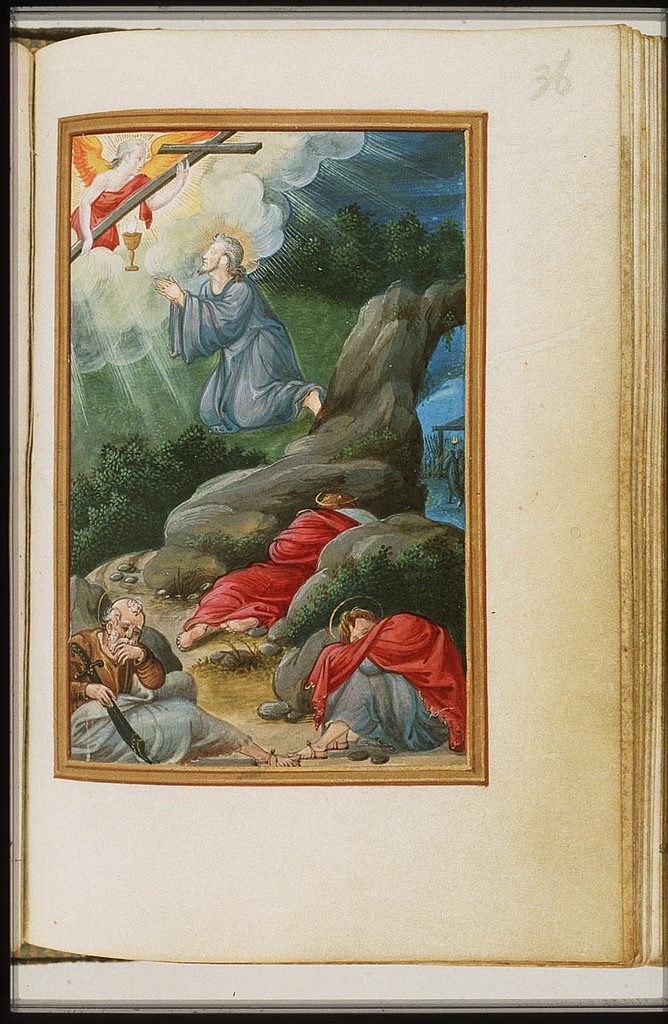

Matthew took this directly from Mark’s account of Jesus’ own prayer in Gethsemane:

“Abba, Father,” he said, “everything is possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will.” (Mark 14:36)

The idea of surrendering one’s own will to God’s appealed to Matthew so much that he repeated it, though Mark only had Jesus say it the once:

Going a little farther, he fell with his face to the ground and prayed, “My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will.”

He went away a second time and prayed, “My Father, if it is not possible for this cup to be taken away unless I drink it, may your will be done.”(Matthew 26:39, 42)

On Earth As It Is in Heaven

Goulder sees this phrase as another instance of Matthew being Matthew.

The association of heaven and earth comes thirteen times in Matt., compared with twice in Mark and five times in Luke. (Goulder, 40)

But what does “as it is in heaven” mean, exactly? Either

May your will be obeyed by men as it is by angels

or

May your will be done on earth as it is laid down in heaven. (Compare 1 Maccabees 3:60: “But as his will in heaven may be, so shall he do.”)

Either way, but especially if the latter is meant, then from the points about Luke’s reluctance to repeat thoughts that we saw in the previous post we may well appreciate Luke’s opting to omit it.

And Lead Us Not Into Temptation

Again we see the source in Jesus’ instruction to his disciples in the Gospel of Mark, this time when Jesus warns his disciples what to pray for when with him on the eve of his trial and suffering:

Watch and pray so that you will not fall into temptation. (Mark 14:38)

The old question: What does “temptation” here mean? Does it mean “trial”, “test”, or does it mean a luring or seduction to follow the way of evil? The Greek word (πειρασμός) can mean either.

- Hebrews 3:8 it refers to “tempting God“;

- 2 Peter 2:9, Luke 8:13, Acts 20:19, 1 Peter 1:6, 4:12, Revelation 3:10 it refers to tribulation;

- Luke 4:13, 1 Corinthians 10:13, Galatians 4:14, 1 Timothy 6:9, James 1:2, 12 it refers to “the lure of the devil“.

In the Gethsemane prayer, Luke 22:40, the exact meaning is unclear but Goulder comes down on the side of it meaning tribulation because Jesus is praying for himself to be allowed to bypass the cup, the tribulation, and it makes sense that Jesus would be admonishing his disciples to pray the same.

Further, in Mark 13 the word is used to describe the trials and tribulations of the “last days” and we see the image continue into Jesus’ own Passion:

St. Mark has made it plain that the Passion of Jesus is to be continued in the later passion of his church: and the repeated warning [to watch] to the disciples in Gethsemane makes it more likely that the ‘temptation’ they are to pray not to enter into is the refining tribulation, beginning with the cross. (Goulder, 42)

And Deliver Us from [the] Evil [One]

Just as Matthew rounded off “your will be done” with “on earth as in heaven” so he rounded off “lead us not into temptation” with “but deliver us from the evil one” — both unnecessary glosses, in Luke’s view, presumably. Luke omits both.

Your Kingdom Come

Another Aramaic expression that appears to have had wide currency in the early Church(es) — certainly pre-dating the gospels — is Marana Tha, Come our Lord.

If anyone does not love the Lord, let that person be cursed! Come, Lord [= Marana tha]! (1 Cor. 16:22)

He who testifies to these things says, “Yes, I am coming soon.” Amen. Come, Lord Jesus. (Rev. 22:20)

“Remember, Lord, thy Church to deliver it from all evil and to perfect it in thy love ; and gather it together from the four winds even the Church which has been sanctified into thy Kingdom which thou hast prepared for it; for thine is the power and the glory for ever and ever. May grace come and may this world pass away. Hosanna to the God of David. If any man is holy, let him come ; if any man is not, let him repent. Marana tha. Amen.” (Didache 10:5 f)

Matthew does not open his prayer request with Let our Lord come!” but, since he is addressing the Father directly and because he equates the coming of the Son of Man or Lord with the coming of the kingdom, he rephrases the common church saying as Thy Kingdom Come.

Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread

We know that Matthew had the Ten Commandments in mind when he composed the Sermon on the Mount. Jesus delivers his commands from a mountain just as the ten commandments were delivered on a mountain, and Jesus addresses specific commands — murder, adultery — to give them a “more spiritual” interpretation.

If the Sermon on the Mount is based on the Ten Commandments and wider law as given according to the Mount Sinai episodes in Exodus, the Lord’s Prayer within that sermon likewise follows the pattern of the Ten Commandments, Goulder suggests.

So, the first five commands are generally understood to be addressing God and obligations we have towards him, while the last five address human relationships. Ditto for the Lord’s Prayer. The first clauses address the concerns of God with the worshipers’ concerns kept in the background.

- hallowed be your name,

- your kingdom come,

- your will be done,

- on earth as it is in heaven.

The last clauses address “our” needs:

- Give us today our daily bread.

- And forgive us our debts,

- as we also have forgiven our debtors.

- And lead us not into temptation,

- but deliver us from the evil one.

So with “Give us this day our daily bread” we begin the second half of the Prayer in accordance with the template from the Decalogue. (Does this request further imply a higher answer to the Decalogue’s warning against coveting?)

For Matthew, not being anxious but trusting God daily for our daily needs is important enough to warrant an extended lesson in the Sermon on the Mount: see Matthew 7:7-11. So it becomes part of the Lord’s Prayer,

Give us this day our daily (= ἐπιούσιον) bread.

Goulder points out that that Greek word for “daily” (ἐπιούσιον) is rare and was of uncertain meaning even for the Church Fathers. Though correct, it appears to have bothered Luke somewhat, too, because he reworded Matthew’s line to clarify the meaning of the passage. For this purpose he drew upon another scene from the Exodus, one he knew from the Septuagint or Greek translation of the Scriptures, that illustrated the same lesson of the need to trust God daily for each day’s needs, including bread.

And the Lord said to Moses, Behold, I [will] rain bread upon you out of heaven: and the people shall go forth, and they shall gather their daily portion for the day, that I may try them whether they will walk in my law or not. And it shall come to pass on the sixth day that they shall prepare whatsoever they have brought in, and it shall be double of what they shall have gathered for the day, daily.” (Exodus 16:4-5, LXX)

The Greek for the bolded phrase is τὸ καθ᾿ ἡμέραν εἰς ἡμέραν = For (according to) the day, daily.

That turn of phrase clarified Matthew’s obscure ἐπιούσιον and it had the double merit of being most aptly scriptural. So Luke worked it into the petition:

| τὸν ἄρτον | ἡμῶν | τὸν ἐπιούσιον | δίδου | ἡμῖν | τὸ καθ’ ἡμέραν |

| the bread | of us | daily | give | us | each day |

in place of Matthew’s

| τὸν ἄρτον | ἡμῶν | τὸν ἐπιούσιον | δὸς | ἡμῖν | σήμερον |

| the bread | of us | daily | grant | us | today |

Hallowed Be Your Name

We saw above that Matthew’s gospel was in some ways intended to be a rewriting of the Old Testament Law. To expand a little on that point, Matthew effectively covered the first and second of the Ten Commandments with Jesus’ rebuttal to Satan in the wilderness:

Jesus said to him, “Away from me, Satan! For it is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God, and serve him only.’” (Matthew 4:10)

In Matthew 12:8 we read the response to the fourth commandment when Jesus declares himself the Lord of the Sabbath and the purpose of the Sabbath for mankind. In chapter 15 Matthew has Jesus castigate the religious authorities of the day for making light of the fifth commandment to honour parents. Coveting is taken care of as we have seen with admonitions not to worry about any physical need. But what of the third commandment, Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.

Matthew makes the first request in the Lord’s Prayer answer to the third commandment by drawing “hallowed/holy” from the fourth commandment to keep the sabbath holy.

–o–

| Lord’s Prayer Passage in the Gospel of Matthew | Proposed Source (Michael Goulder) |

| Our Father in heaven | from Jesus’ teaching on prayer in Mark (Mark 11:22-25) |

| Hallowed be your name | from the 3rd and 4th of the Ten Commandments |

| Your kingdom come | from Marana the (Come our Lord) |

| Your will be done | from Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane (Mark 14:36) |

| on earth as it is in heaven | Matthew |

| Give us today our daily bread | Decalogue template |

| And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. |

from Jesus’ teaching on prayer in Mark (Mark 11:22-25) |

| And lead us not into temptation, | from Jesus’ instruction to his disciples in Mark (Mark 14:38) |

| but deliver us from the evil one | Matthew |

–o–

For an earlier (2014) post setting out Michael Goulder’s arguments in the 1963 JTS article see The Composition of the Lord’s Prayer

–o–

Goulder, M. D. 1963. “The Composition of the Lord’s Prayer.” The Journal of Theological Studies XIV (1): 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/XIV.1.32.

Manson, T. W. 1955. “The Lord’s Prayer: II.” Paper. The University of Manchester Library. John Rylands Library. https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:1m1891&datastreamId=POST-PEER-REVIEW-PUBLISHERS-DOCUMENT.PDF.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Yeah, I don’t find anything here that I disagree with. I’ve never worked through this or seen it broken down in this way, but it makes a lot of sense.

How does one account for Didache? It doesn’t seem aware of a preceding Jesus as a human being or teacher and reads like the non-Markan G.Mtminus its framing narrative. In the Hag Hammadi texts you find The Sophia of Jesus Christ taking the teaching found in Eugnostos the Blessed and putting it into the mouth of Jesus. I would hazard the same thing has been done with Didache by the Matthean author. We don’t need, and have never needed, a hypothetical “Q” document it would seem to me: Didache and G.Mk. G.Mt is, amongst other things, myth to account for the praxes exampled in such as Didache; The Lord’s Prayer episode in G.Mt is an aetiology for the prayer found in Didache. See Mack, Myth and the Christian Nation for myth authorizing ritual; and RobinsonThe Hag Hammadi Library. Another, it seems to me, obvious missed or discounted due to the unexamined assuming of Jesus. I think itt better accounts for, and for more, of what we find than other hypotheses. My two penn’orth, YMMD.

Stephen Watson : If our host wills it that we link our own blogs in his comments, I have an answer in the link to my name here.

The short answer is: Matthew (or whoever) constructed The Lord’s Prayer specifically that it escape his Gospel and head out into the wilderness, to prepare the way… as it were. The Prayer seems to have done just that in the Syriac tradition, since this is partially in rhyme (Syrians were big on rhyming rhetoric: it’s called memré).

If pericopae from the Gospels could get translated and adapted into Syriac, in advance of the full Gospel there; someone could slip them out of the Gospels and pass them to Anatolia in Greek too.

Thanks David, I’ll take a proper look at your blog in the next week or two. I can sort-of-see where you are coming from but need to be more familiar with your context. However I don’t see how this accounts for the rest of Didache. It seems ignorant of everything non-Marcan in G.Mt, not just the prayer.

Ignorant of “Jesus” that is.

Matthew did by absolutely no means invent the prayer, it’s one more of the audacious accusations invented by Markan prioritists.

The prayer is at the end of a long history of redactions, as are about all forms of the new Testament.

To the Lukan parallel, there is a medieval variant which requests the emission of the Holy Spirit instead of the coming of the kingdom. This makes the prayer an epiclesis, and this is highly reasonable in the context of Luke 11. “Luke” explains that the Father will not deny the Holy Spirit to anyone who inquires for it. The received text does in no way justify this statement, whereas the manuscriptural variant does so perfectly.

Further, the introduction to the prayer in Luke reveals that the prayer, in a more original form, was assigned to John the Baptist: The letter’s disciples implore Jesus to provide them withn a simimilar prayer to those of the former, that is, a baptismal prayer/epiclesis. The primary purpose of the prayer is thus one of imploring the Father to send the Holy Spirit to purify the canditate of the baptise.

Transferring the prayer to Jesus involved the addition of the request of the kingdom to come, as this was the main subject of Jesus’ kerygma. Further, the request for the daily bread was added because Jesus has instituted the eucharist by performing the miracle of the mass feeding.

The request for purification is expressed in two ways: The forgivenness of sins and the lifting of temptation.

The Matthean version added the attribute “in heaven” to “Father”, for the Jewish god is not habitually called father in the hard core of the Old Testament; rather, Jews considered Abraham ans their common father. For liturgical use, the prayer was shaped like a psalm, using the techniques of X-asms and parallelisms.