While looking over my notes from the past few years, I came across something I wrote to Valerie Tarico. She had asked Neil and me to take a look at an extended version of her article, “Why Is the Bible So Poorly Written” (which is, unfortunately, behind a paywall).

In the draft we received, she quoted Ken Jacobsen, a graduate of Princeton Seminary, from a comment he made at Quora. Here’s what he said.

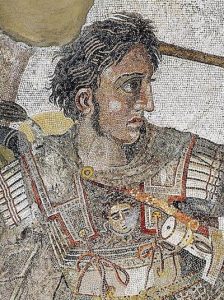

Koine Greek is pidgin Greek… developed by Alexander’s armies to communicate, not to impress. It’s a step down from Classical Greek.

That statement is wrong in at least two respects. Below was my response to Valerie, edited slightly.

First, I would never call Koine a pidgin. Jacobsen should have called it a lingua franca. Koine Greek is simplified Attic Greek, where a great deal of case collapse, pronunciation collapse, smoothing, etc., has occurred, which makes it easier for foreign speakers to learn. (The process is often referred to as “dialect leveling.”) You already know the history of its spread throughout the east.

The key point here is that Koine actually was a primary and a complete language, often used as a trade language.

On the other hand — “A pidgin is a language with no native speakers: it is no one’s first language but a contact language.” (Ronald Wardhaugh) Ref.: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (p. 57 ff):

The reason for the roughness of Mark’s gospel and for the dumpster fire of John’s Revelation is not an intrinsic problem with Koine Greek, but with the abilities of those writers for whom Greek may have been a second (or even a third) language. Jacobsen calls it a “step down from Classical Greek,” which is more of an aesthetic judgment call than a useful objective statement. After all, many writers from that period had no trouble at all expressing themselves in it — e.g., Polybius and Plutarch.

From Wardhaugh again, p. 55 (emphasis mine):

A lingua franca can be spoken in a variety of ways. Although both Greek koiné and Vulgar Latin served at different times as lingua francas in the Ancient World, neither was a homogeneous entity. Not only were they spoken differently in different places, but individual speakers varied widely in their ability to use the languages. English serves today as a lingua franca in many parts of the world: for some speakers it is a native language, for others a second language, and for still others a foreign language.

Unfortunately, too many NT scholars learn Greek from the inside out. They start with Koine, and they’re lucky if they even dabble in the more ancient forms. They learn from their instructors that classical Greek was “more expressive” or “more elegant.” This is nonsense. All languages used by humans serve the needs of their speakers. Is Elizabethan English “better” than Modern English? Is Chaucer’s English “a step up from Modern English”? Of course not.

Beware: Many Biblical scholars don’t know what they don’t know.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

In addition, much of what has been made about Mark’s “poor Greek” is actually nonsense. Many of the things that various people over the years have identified as grammatical flaws in Mark are either the result of the literary references the author is making, or are things done in order to fit the chaistic style Mark is using, or are taken from cues in the Septuagint where the author is emulating language usage found there.

So the idea that “Mark” was poor writer or didn’t know how to write proper Greek is not actually in evidence. What is more often the case is that the author was using complex literary structures and references that many reads have failed to recognize and thus not understood his word choices. He wasn’t a poor writer, he was writing in codes that were so complex few people have grasped them.

Modern English is much the same compared to Anglo-Saxon and we wouldn’t call it a pidgin. And for the same sorts of reasons. Successive Scandinavian occupiers, Danes and then the Normans, imposed their languages on some segments of the population such that English lost most of its grammatical complexity as “native” speakers in different regions found it difficult to communicate and the occupiers probably made use of a debased form of English as a second language for communicating with their native servants and retainers.

The simple answer to Valerie Tarico’s question is that the NT is not written in literary Greek, which was the preserve of an intensively educated social elite. That the question was raised in antiquity is apparent in Origen’s ‘Contra Celsum’ :

1.62 : of the apostles, “in them there was no power of speaking or of giving an ordered narrative by the standards of Greek dialectical or rhetorical arts…The truth of the claim that his teaching is divine would no longer have been self-evident…if the gospel. .were in persuasive words of the wisdom that consists in literary style and composition”.

3.39 : “We also believe in the honest purpose of the authors of the gospels..men who had not learnt the technique taught by the pernicious sophistry of the Greeks, which has great plausibility and cleverness, and who knew nothing of the rhetoric prevalent in the law-courts, could not have invented stories in such a way that their writings were capable in themselves of bringing a man to believe..Jesus chose such men to teach his doctrine that there might be no possible suspicion of plausible sophisms but that..the innocence of the writers’ purpose,which if I may say so was very naive, might be obviously manifest. .The writers were..endowed with divine power, which accomplished far more than seems to be achieved by involved verbosity and stylish constructions, and by a logical argument divided into distinct sections and worked out with Greek technical skill”.

Origen, of course, was a highly-educated man, and used his own ‘Greek technical skill’ to answer objections to the value of the NT raised by his class.