We sold our house in Iowa last summer. After working on it for months, getting it into shape, we decided it was ready to put on the market. Surprisingly, it sold in a single day. A couple came to look at the house the evening it was listed, and they immediately put down an offer. Joy and panic ensued.

Over the decades, like all good Americans, we had accumulated a vast amount of junk. Well, not all of it was actual junk, but we tend to hang onto objects just for the sake of hanging onto them. In the month between selling and vacating that house, I drove back and forth between Amana and Cedar Rapids over and over.

Some stuff we donated. Other stuff we threw away. The rest went into storage.

On those late afternoon trips, heading back to the RV park, I usually listened to audiobooks or lectures. But once, I had wrongly estimated the remaining time and was left with silence. While searching through the FM radio dial for something worth listening to, I came upon two radio stations.

The first was a protestant evangelical station. The minister was telling his audience that Christians should spend as much time as possible every day reading the Bible. It is the word of God, he explained, and you can’t make any better use of your time than being in the presence of the word of God.

I flipped to a frequency nearby, which turned out to be a Catholic station. We apparently have a significant population of Roman Catholics in the area, enough to warrant a station devoted to Catholicism. I’ve driven all over the Midwest, and I can’t recall ever stumbling upon a Catholic station until I lived in Cedar Rapids.

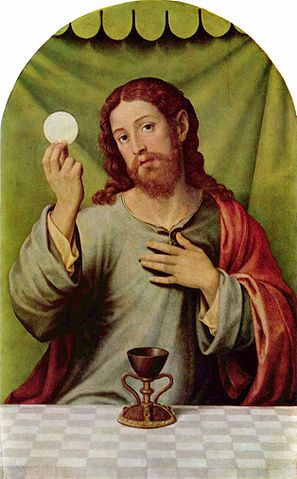

The speaker on the Catholic channel said that if Christians could manage it, they should spend a part of every day in the presence of Christ, that is to say, taking the Eucharist. Imagine living every day in the body of Christ, partaking of his love and sacrifice to humankind. What could be better?

It struck me that I had accidentally found — minutes apart — an explanation of the greatest divide between the two branches of Christianity. One focuses on the “Word of God,” while the other focuses on the “Body of Christ.” For Protestants, the Bible tells them the good news that Christ died for them. But for Catholics, the Bible is a supporting pillar of the faith, but neither the end goal nor the vehicle to salvation.

We Protestants and ex-Protestants tend to know very little about other faiths, especially the one we grew out of (or broke away from). My ministers and Sunday School teachers told me that Catholicism was bound up in ritual and had lost sight of the true nature of salvation. True forgiveness, they explained, came from a personal relationship with God.

I would argue the Catholic belief in the Eucharist as the “sacrament of sacraments,” with the understanding, in the words of St. Thomas Aquinas, that “all the other sacraments are ordered to it as to their end,” helps explain the origins and spread of Christianity. People like me who grew up in the Protestant tradition tend to place too much emphasis on the Gospels and other writings as the building blocks of Christianity.

When Bart Ehrman talks about people sharing stories of Jesus, his words and deeds, and about belief in him spreading like wildfire across the Mediterranean basin via word of mouth, I think he’s suffering from a largely Protestant delusion about how religions spread. Christianity was less a set of beliefs about the past maintained in tradition than it was a package of communal rituals tied to a framework of beliefs. Meeting together, singing, praying, and listening to the local church leaders speak — all of these parts of Christian fellowship played a role. However, what cemented one’s place in the community of Christians were the two essential rituals: baptism and participation in the Eucharist.

I suppose we could mark it down as a sign of Christianity’s amazing resiliency that the Protestant Reformation managed to remove the role of priests completely as a conduit between God and man, to take away the need for priests to transform the bread and wine into the actual body and blood of Christ, and to push Holy Communion off to the side as “something we do from time to time.” Recently, while reading some detailed histories of the Crusades, I couldn’t help notice how great a role the Eucharist played in people’s lives at the time. Of course, thorny issues arising from indulgences and purgatory would follow. And the corruption surrounding them would eventually help lead to schism and continental war.

In order to understand the origins and history of Christianity, amateur and professional historians alike would do well to remember that the religion practiced in most Protestant churches today is far different from the one to which Constantine converted. In the first millenium of the common era, the symbols of the Christian juggernaut were not the cross and the Bible, but rather the crucifix and the chalice.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“and to push Holy Communion off to the side as “something we do from time to time.””

I attended Baptist church pretty regularly until I was 18. In all that time I only saw the Eucharist once. Couldn’t believe my eyes. I wondered what the heck was going on.

Once I learned the history of the church, it was quite an amazing thing to look back on. How did it become just a sideshow when it used to be the primary ritual?

I was first introduced to the Eucharist at the Methodist church. I went there because lots of my classmates in jr. high/middle school went there. I witnessed it a time or two there. So I’m really not that familiar with it. I also witnessed the “unknown tongue/speaking in tongues” at my cousin’s church (holy rollers). Quite a sight. This lady got up, starting blabbering during the service and then the preacher translated what she said. I was about 15 or so. Didn’t believe a word of it.

Re: Bart Ehrman and Protestant bias, I’ve come to the conclusion after extensive study of comparative ancient religion that this bias or lens impacts the whole enterprise and that, in short, if Protestantism is taken as the model of “a religion” then it was the first religion. This sense of an arena set apart from the secular and characterized as primarily a set of beliefs, undergirded by scripture, simply did not exist in the ancient world, or, indeed, before the Protestant revolution.

I agree that early Catholic/Orthodox Christianity was more ritualistic and tribal, communal. Though I’d say that the Protestants partially splitting “religion” away from that, achieved a transitionally useful thing; believers could compartmentalize religion to a degree. To keep it from interfering too much with our practical jobs, and advancing modern knowledge.

And by making “Religion” something 1) somewhat separate, and something 2) centered on a book, on literacy, it became possible to begin studying religion, somewhat more objectively. Though by now we know that religious devotion still continues to deform the work of even Protestant scholars of religion.

It’s certainly true that while many people tend of think of Christianity as the definition of what religion is, Christianity was very different from all prior religions, even by the 2nd century. And it has only become more unlike traditional religions over time. Christianity and Islam are actually outliers that are not representative at all of what religions were like prior to their rise. Prior religious belief was far less dogmatic, or perhaps not dogmatic at all. Religion was more ritualistic and less about faith or ideas. Less about the afterlife and more about the present, etc.

Christianity was a new religion that sprang up out of recent writings, which was very unlike most religions that had developed slower over time through layers of traditions. Christians pointed to writings and said, “These are the facts of our religion,” which just isn’t something that happened prior to that.

Are you familiar with the Milindapañha? It is presented as discussion between a Buddhist missionary and a Greek King in which the misiionary, Nagasena by name, repeatedly cites Buddhist texts in order to establish what Buddhists believe. It is set during the Second Century BCE.

Not sure if I’m misunderstanding you but this is all found in Egyptian religion and Greek mystery cults long before Christianity. They may have not been as dogmatic as Christianity and Islam but if you didn’t join a mystery cult, weren’t a follower of Osiris or any other mystery cult savior, and didn’t live a life of certain morals, you were pretty much doomed in the afterlife. The afterlife was one of the most important aspects of these religious cults.

I do’t know enough about Egyptian religion to really comment on that. I’m not sure what the day-to-day religious beliefs of average Egyptians were. Mystery cults were, themselves, relatively new forms of religion as well and not the mainstream.

Most ancient religious practices had to do with warding off evil, ushering in good harvests, providing support for rulers, bringing about successful childbirths, etc. Most religions revolved around making life on earth in the present better – calling on gods and spirits to be protective, helpful, etc.

Even Judaism is mostly about the present – trying to please Yahweh so he will bestow rewards on the people or to prevent punishments – following his laws so that misfortune doesn’t befall either the individual or the community.

Oh yeah, “pagan” religions definitely had this element to them but they also had an element that focused on personal salvation and morals like Christianity. The latter was very important in Egyptian religion, Greek philosophy like Platonism, and the mystery cults.

It depends what you mean by “mainstream” and “new”. “New” according to what period of time? A lot of them started out as being not really accepted by the state but eventually became accepted, very much like Christianity. The mystery cults attracted a lot of lower class people, slaves, and just the common people in general because they offered a personal relationship with a deity. That’s not to say that rich and powerful people didn’t join them too.

Oh yeah, “pagan” religions definitely had this element to them but they also had an element that focused on personal salvation and morals like Christianity. The latter was very important in Egyptian religion, Greek philosophy like Platonism, and the mystery cults.

Not really. Egyptian religion was certainly concerned with immortality, but for who, and on what terms? Originally, when the Pyramid texts were first in use in the Old Kingdom, it’s clear that “awakened” immortality was for kings. Everybody could look forward to some kind of existence in the afterlife, but it had nothing to do with morality. For common people, the underworld was conceived as a dreary, dusty place where one would have a shadowy existence of eternal sameness, whether you were a terrible person or kind and generous. The magical rituals prescribed in the Pyramid texts, and later the coffin texts which became the famous “Books of the Dead” in the New Kingdom, were concerned with awakening the king in the afterlife as the latest Osiris. An “awakened akh” was a potent force in the world, to whom cult sacrifices were made, and, as Osiris, he was king of the afterlife as his “son” was Horus, king on Earth until it was his turn. Part of the test or trial that the magical rituals were intended to help the deceased king pass through concerned a recounting of royal deeds, in the negative: “I did not do X, I did not do Y”, but this was a matter of king-craft, not personal morality as we understand it. And the important thing to remember is that the key was the priests had to get all the magic rituals right, or it didn’t happen. It was the actions of the living, after the deceased was gone, that actively aided the awakening to immortality.

Similarly, in the Greco-Roman mystery cults, what you believed had nothing to do with it. It was what you had experienced, the initiation ritual and the mystery itself, which was a communal ritual or revelation that was secret in the sense of taboo to speak of. That is, it wasn’t taboo to know about it if you weren’t an initiate, it was taboo to talk about it if you were. They were also expensive. You needed to have the means to travel to the cult location, Eleusis et al, and you had to pay the initiation tithe or fee. There was some element of moral discrimination, as those notorious for their conduct were refused, but that’s less about personal morality and more about social censure.

Neither of these things had any of the elements of Protestant Christianity, in which faith –a matter of internal, personal belief independent of experience or ritual– is sufficient to secure personal salvation.

(You mentioned Greco-Roman philosophical religion too, which is closest perhaps, but it was very much an elite concern, and not very relevant to the way the majority experienced and understood religion.)

One reason the Bible was foundational to Protestantism was surely because (if I’m not mistaken) for the first time there was a large contingent of adherents that could read and own books. I would say that belief systems were vitally important before then, in any case, otherwise why all the fuss about adhering to creeds, and the dire need to stamp out all other religions (including minor divergences from orthodoxy) within its sphere of influence, going back to Roman times?

The Romans, and most cultures, were very religiously tolerant. Prior to the rise of Christianity there were thousands of gods being worshiped within the Roman empire. The only thing the Romans enforced was the adherence to various state rituals and tithing, but as long as you did your official duty for the state they didn’t care what you believed.

Many cultures believed that the various gods worshiped by different cultures all represented the same gods, i.e. that Zeus = Jupiter = Horus = Ahura Mazda = Yahweh, etc., etc. (I’m not sure on the particular god equivalents here, just throwing out examples).

The Romans had no problem allowing conquered peoples to continue worshiping their own gods.

Oh yes of course. In case I wasn’t clear I was referring to the dogmaticism of Christian orthodoxy under pagan Roman rule.

The Christians were dogmatic because they believed that they had confirmed evidence that there was only one true god and religion. This was based on their (mis)understanding of “prophecy” as reflected in the Gospels. So much had to do with specific readings of the Gospels, and a lot of that all traces back to the way that the Gospel of Mark was written, using many scriptural references, which were interpreted as secret codes that confirmed divine knowledge.

Are we addressing dogmatism or intolerance? What you describe is what groups of Christians were dogmatically intolerant about but I don’t see how those beliefs themselves were a cause for intolerance.

Yes,

oh Yes Tim,,, the anachronistic re-readings, which we all are susceptible to , they often affect the attitudes and approaches to texts,, so distant and strange from ourselves…

Yes, Tim,, the NT is a an arbitrary canonical document of differences that all of us, all who are in search for the exact key which we think we can finally find…

why oh why are we so scared over getting all these divergent views and hermeneutical “hunches” of such texts ..wrong..!???!

I am so sad over the terror and fear that biblical and theological hermeneutics and scholarship and agendas that have overshadowed and even hindered honest scholarship of such fascinating ancient texts. This is so sad and makes me mad!

Don’t let anyone of us get scared despite what some ancient text 2 Peter, etc. (considered a forgery by many) threatens with severe judgement for those who “twist “scriptures…

Polemic Catholicism has its hands in the NT and then used by Protestants to keep their own ” true ecclesia which Jesus supposedly promised .. essentially the so called Catholic Religion which is prominent today and considered to possess the real, “canon”…

even though Protestants call forth their own subjectively decided “canon”..or rule of faith and so called faith..or better yet (“the faith”..a common phrase in the NT which has nothing to do with any subjective “feeling” faith experience, It became a “the faith” thing,, the faith of the NT is not a subjective feeling thing , it is a dogma to be submitted to , to be obeyed via threat of loss of life, etc.

Thanks again Tim for stirring many things you may not have anticipated in this blog of yours…

Nice to hear from you again on this site… Take care.

I was also raised 1) Protestant. But lived in Catholic areas in Boston and Germany, and the American southwest. So on the way to mythicism and atheism, I seriously looked into 2) “The” Church.

However? Today I often suspect that the key to scholarly understanding of the genesis of Christianity is probably 3) the social sciences, like anthropology; 4) History; and maybe after Catholicism, a 5) a closer look at the third most popular church. That is? The Orthodox churches.

Especially? The Greek Orthodox Church. Which was always very close to say, eastern and Greek myths.

Let’s never forget that the earliest NT texts we have, were written in Greek.

The Orthodox churches are not well known in America. But their doctrines begin to explain some key non-Catholic features of the New Testament. In particular, orthodox dogma does not seem so sold on the full divinity or trinitarian status of Jesus. Still preferring the gruffer OT God the “Father.” Who seems to have higher status than Jesus.

And by the way, Orthodox churches are very very tribal and community-centered too.

I wish more Christians would read the Bible. As Asimov said, the Bible is the fastest route to atheism :p

Also, I figured that the best way for Christians to spend their time would be serving the needy…

Drinking beer.

Wine might almost make that sacred. Especially in dionysiac and Bacchic and Eucharistic (if not Superbowl) rituals.