The previous post concluded with

Thus I think we need to look between 70 and 135 both for the author of the Vision and for the one who projected it into Paul’s letters. We are not necessarily looking for two people. There is no reason why one and the same person could not have done both tasks.

Continuing . . . .

…

The Best Candidate

To my mind easily the best candidate for both tasks is a man whose name is variously rendered as Saturnilus, Saturninus, or Satornilos. A Latin mistranslation of the name in Irenaeus’ Against Heresies is believed to be the source of the confusion. The original Greek version of that work is not extant, so there is presently no way to be sure. In this post I will use the first rendering: Saturnilus

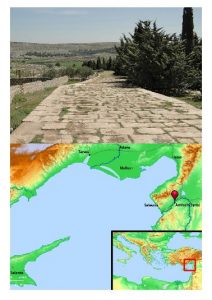

The information available on this man consists primarily of two paragraphs in the aforementioned Against Heresies (1.24.1-2). Though meager, I think it is sufficient to establish him as our lead candidate. He lived in Syrian Antioch and founded a Christian community (or communities) sometime within our target period of 70 to 135 CE. Prior to becoming a Christian he was a Simonian. Irenaeus says he was a disciple of Menander, Simon of Samaria’s successor. At some point, however, Saturnilus apparently switched his allegiance. Although Simon and Menander had put themselves forward as Savior figures, it is Jesus who is named as Savior in the teaching of Saturnilus. Alfred Loisy puts it this way:

In many respects, therefore, he (Saturnilus) was a forerunner of Marcion. Though much indebted to Simon and Menander, he, unlike them, does not set himself up as the Saviour sent from on high, but attributes that role to Jesus. Consequently, heretic though he be, we cannot deny him the qualification of Christian, while, from the Christian point of view, Simon and Menander qualify rather for Antichrists. (La Naissance du Christianisme, ET: The Birth of the Christian Religion, translation by L.P. Jacks, University Books, 1962, p. 302).

Justin Martyr includes Saturnilians among those who consider themselves Christians, though he himself views them as “atheists, impious, unrighteous, and sinful, and confessors of Jesus in name only, instead of worshippers of him” (Dialogue with Trypho, 35). Justin’s doctrinal objection is that “some in one way, others in another, teach to blaspheme the Maker of all things, and Christ, who was foretold by Him as coming, and the God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and of Jacob.” According to Irenaeus, Saturnilus believed God to be “one Father unknown to all,” and that the God of the Jews was in reality just one of the lower angels, one of the seven who made the world. Such beliefs are not explicitly present in the Vision of Isaiah but may be implicit. God there is called Father but never maker or creator of the world. In fact, the world is “alien” (Asc. Is. 6;9), and so is the body (Asc. Is. 8:14), and so are the inhabitants of the world (Asc. Is. 9:1). True, the angels of the world are not referred to as its makers either, but they appear to have been in control of it from the beginning and are not afraid to say “We alone, and apart from us no one” (Asc. Is. 10:13). Regarding Jesus, Saturnilus was a docetist, teaching that he only appeared to be a real human being (Against Heresies 1.24.2). As we have already seen, the Jesus of the Vision’s “pocket gospel” was docetic.

Saturnilus’ Simonian past, however, provides us with another connection to the Vision of Isaiah. The main storyline of that writing is an ancient one, going back, as Richard Carrier points out in his book On the Historicity of Jesus (pp. 45-47), to the Descent of Inanna. It is a storyline that has been adapted and adopted many times in history, including by Simon of Samaria and Menander. The points of contact are obvious in what Hippolytus says about Simon’s teaching:

For as the angels were mismanaging the world, owing to love of power, he (Simon) had come to set things straight, and had descended under a changed form, likening himself to the Principalities and Powers through whom he passed, so that among men he appeared as a man, though he was not a man, and was thought to have suffered in Judaea, though he had not suffered. – Refutation of All Heresies, 6, 19.

And this from Epiphanius:

But in each heaven I changed my form,” says he (Simon), “in accordance with the form of those who were in each heaven, that I might escape the notice of my angelic powers and come down to the Thought, who is none other than her who is also called Prunikos and Holy Spirit, through whom I created the angels, while the angels created the world and men. – Panarion, 2.2

The Vision of Isaiah could be yet another adaptation — this time a Christian one — of an earlier writing, and this time done by someone who was already familiar with such things — a former Simonian. God knows it has enough rough edges to justify seeing it as a reworked text. So I would slightly modify Simone Petrement’s suggestion that “it may have been written by a Simonian, around the time of Menander” (A Separate God: The Christian Origins of Gnosticism, p. 326). Make that: by an ex-Simonian named Saturnilus.

…

A Pauline Saturnilus

Having pointed out some possible connections between Saturnilus and the Vision of Isaiah, I want to now make a few observations regarding his brand of Christianity. Irenaeus doesn’t say anything that expressly ties him to Pauline Christianity. Irenaeus does know, however, of Cerdo, who is the earliest figure expressly associated with a collection of Paul’s letters. And Epiphanius says Cerdo, who “took his cue from Simon and Saturnilus” (Panarion, 41,1,1) immigrated from Syria to Rome in the time of Bishop Hyginus. This would put Cerdo first in the ambit of Antioch, possibly while Saturnilus was still alive. Then it next puts him at Rome shortly before Marcion’s own arrival there. There is a definite family resemblance, say the early heresy-hunters, between Simon, Menander, Saturnilus, Cerdo and finally the ultimate Paulinist, Marcion. For this reason Saturnilus’ Christianity is believed to have been of the Paulinist type.

Indeed when we examine closely the bits of information Irenaeus gives us about Saturnilian Christianity we find material that matches up reasonably well with issues treated in Paul’s letters. For instance, Ireanaeus says that many Saturnilians abstain from eating meat. That means that some didn’t. And the same could be said about Pauline Christians. Some abstained from meat. In Romans 14 they are called “the weak.” The ones who didn’t abstain are called “the strong.” The situation is a bit fuzzy in Romans and so many commentators advise that we should turn to 1 Corinthians for clarification. There the meat problem is clearly related to its being offered first to the gods. Some Corinthian Christians had no problem with this since, they argued, the gods of the pagans don’t have any real existence anyway. But others did have a problem, for they believed that some kind of communion with demons was established by eating the meat. It is almost as if we are sitting in on a church meeting and getting a number of viewpoints. Were all the viewpoints Paul’s? Or are we getting the viewpoints of Spirit-filled Christian prophets who are channeling Paul? Hard to say. But this may be the context in which we should understand Saturnilian abstention from meat.

Another example: According to Irenaeus, Saturnilians say that marriage and procreation is from Satan. That belief is not as startling as it first seems. Saturnilians believed that the world was made by seven lower angels. So in attributing marriage and procreation to Satan they are merely assigning to one of those angels the words of Genesis: “Be fruitful and multiply.” Satan appears to be their name for the world-making angel who went on to become the God of the Jews. (Satan means “adversary” and according to Basilides, another disciple of Menander, the God of the Jews was an adversary of the other world-making angels).

In any case, marriage would be downgraded by assigning it to any of the world-makers. And that seems to be the real issue here. Irenaeus doesn’t say that Saturnilians reject marriage. He says they attributed it to Satan. So, in other words, they rated celibacy higher. And again, the same is true in Pauline Christianity. In chapter 7 of 1 Corinthians Paul is made to say that he wishes everyone was celibate like him. As a concession he allows the married to have sexual intercourse “so that Satan will not tempt you because of your lack of self-control” (1 Cor. 7:5). And again, was it Paul who wrote that? Or a Spirit-filled Christian prophet speaking in his name?

Another example: Irenaeus says Saturnilus taught that the angels made two kinds of people: good and evil. But Paul too seems to believe in two kinds of people. In Romans 9 he speaks of “vessels of wrath made for destruction” and of “vessels of mercy” (Rom. 9:22-23). By means of the first God desires “to show his wrath and make known his power;” by means of the second He “makes known the riches of his glory.” Man has no right to protest, for “who are you, a man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, ‘Why have you made me thus?'” (Rom. 9:20)

So it seems to me that, at a minimum, the Saturnilians are addressing the same kind of issues we see addressed in Paul’s letters. At a maximum, many parts of 1 Corinthians could be providing us with a window not on the church at Corinth in the 50s, but on the Saturnilian church sometime between 70 and 135 CE.

…

Continuing….

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This is truly an amazing share. Much appreciated.

Seeing the synergy between Paul and Satornilus in this way is eye-opening. A new question comes to mind now, what could be the reasons Justin Martyr would reject Satornilus (as impious) yet accept Paul (as an apostle)?

My own two bits on this one is that Justin does not “accept Paul” as an apostle. He nowhere mentions Paul. Presumably, it is said, because Paul was the “apostle of the heretics” — viz Marcionites. Justin did oppose Marcion.

“Justin did oppose Marcion” eventually. There’s hints they had nonconfrontational discourse initially, via an apparent extract preserved in Irenaeus Adv Haers IV,2. There was a ‘To Marcion’ text of Justin (which Eusebius changed to Against Marcion’s Writing; see eccl. hist IV,18,9. ), and a ‘To Marcion’s School’ letter of Rhodo.

That is very interesting and useful … thank you

I’ve been reading his diaglogue with Trypho just now … many of the Justinian concepts seems to be rooted in the synoptics. Justin however mentions that he believes Christ to be born of man but is not of man.

Where does this concept come from? Pauline texts or elsewhere?

About the original gnostic nature of Asc. Isa., the episode of the birth reads:

7And after two months of days, while Joseph was in his house, and Mary his wife, but both alone, it came about, when they were alone, that Mary then looked with her eyes and saw a small infant, and she was astounded. 9And after her astonishment had worn off, her womb was found as (it was) at first, before she had conceived

This Mary is very similar to Eve when the her eyes were opened by the Serpent (=a positive figure, for the Gnostics). And again:

10And when her husband, Joseph, said to her, “What has made you astounded?” his eyes were opened, and he saw the infant and praised the Lord, because the Lord had come in his lot.

Mary and Joseph believe that the son was from the creator god (they “praised the Lord”, afterall), but, in virtue of the fact that also their ignorance has to be assumed about the Son, then the Son has to be from an alien god, different from the creator.

Hence the original gnostic nature of the document.

Roger, two questions:

1) do you think that the birth was found in the gnostic original version of Asc. Isa.?

2) was the Mark’s separationism a way to make Jesus unaware about the his alien nature, by de facto separating him from the his divine nature and so making him really who the his relatives believed that he was: a mere Jew from Galilee?

Of course the eye-opening is an undeniable proof for a gnostic origin of the tale, as is the excursion to Emmaus near the end of Luke and the healing of the two blind men near Jerico in Matthew’s. The other powerful hint is the naming of the lord of the world as Sammael, god of the Blind, for the Lord of the world (the obstinate Jewish god). Sammael is named for the implied blindness of Adam and Eve before the eye-opening scene of the manducation of the apple from the tree of knowledge.

This indicates that the so-called vision of Isaiah has gone through a huge amount of manipulations and copying. In the end, the Catholic manipulator identified the Jewish God nonsensically with The Father, as required by Catholic propaganda; but the editorial fatigue reveals the patchwork and multi-step redaction of the scribbles.

I’m pretty confident that at least the birth narrative in Asc. Isa. post-dates the Gospel of Matthew and is written to address questions about the nature of Jesus’ birth as a result of the Matthew story.

Why is that? What is the basis of your “pretty confidence”? 🙂

Hi Neil,

may you say me where I can acquire this article-review by Prosper Alfaric? Very thanks.

I can only suggest an interlibrary loan or copy.

I am interested in access to the article myself but before I submit a request at a library can you tell me the source of your citation for [Les Epîtres de Paul, in Bulletin du Cercle Ernest Renan n° 35, april 1956. ] please?

Thanks

The source is: Marc Stéphane, La passion de Jésus, fait d’histoire ou objet de croyance, Paris, Dervy-Livres, 1959

At p. 254, the note (9) reads:

Alfaric (article cité p. 252, n. 7) adopte plutot l’opinion de Loisy, quant à l’époque de la “second édition”, édition “mystique” des epitres pauliniennes. Mais, ne croyant pas à une carrière terrestre de Jésus au temps de Tibère, il rejette également la présentation donnée par Loisy et celle qu’adopte Turmel de la conception religieuse de Paul (cf. plus haut, p. 170).

My translation:

Alfaric (article quoted, p. 252, n.7) adopts rather the opinion of Loisy, as for the time of the “second edition”, a “mystic” edition of the Pauline epistles. But, not believing in an earthly career of Jesus in Tiberius’ time, he also rejects the presentation given by Loisy and that adopted by Turmel about the Paul’s religious conception (see above, p. 170).

A very kind soul has sent me a copy of the article that I can share with interested persons!

Thanks!

Could the role of the Jewish Banu Qurayza, who emigrated to the Hijaz region (Arabia), because of the threat of war before and after 70 CE in Judea and beyond, have played a role in a revision of the then strict nationalistic religious Jewish attitudes? Fueled in part by a Nabataean, Sampsiceranium and from Yemen emigrated Banu Qays connection?

Is Paul’s Aretas in fact Harith El Qhitriff, son of Tha’laba II Imru al Qays(Rabbel II?)? Do we end up then according to (2Corinthians 11, in the period +-( 106CE ..140CE)?

Can the study of allegorical texts, later edited or not, be taken seriously as a basis for primary historical research?

Is historical research, based on an understanding of the political social situation, of the entire geographical and the then perception and political tension, much broader than the immediate vicinity of Judea.

Edom, Hijzah, Syria, Nabatea, Sampsigeramus’ kingdom, the philosophical schools of Tarsus and Alexandria, the Zoroastrian molded Greek-Persian-Egyptian-Roman culture molded dynamically and synchretically in a pre-Christian pro-Roman political effort, using a time-evolving synchretic tactic of political-cultural unification?

Was “I/C,S Chrest “is the name of the Lord, and not the name Jesus(codices Vat & Sin), IC has many names to fill.

When was the name of Jesus first mentioned?

Isn’t it better to place religious texts in a historically plausible framework than vice versa?

Just Freethinking

Regards

You probably do know the name ‘Jesus’ was loaded with messianic import. The great warrior successor to Moses and also the branch of Zechariah 6:

“And thou shalt take silver and gold, and make crowns, and thou shalt put upon the head of Jesus the son of Josedec the high priest;

12 and thou shalt say to him, Thus saith the Lord Almighty; Behold the man whose name is The Branch; and he shall spring up from his stem, and build the house of the Lord. (hence messianic expectation that Messiah would tear down and rebuild temple)13 And he shall receive power, and shall sit and rule upon his throne;…

It has long been my contention that ‘Jesus’ was one of many title/names assigned the Christ at the inception of the Christ myth. It was the fusion of the Akedah son sacrifice concept with the Branch/Messiah expectation and the decent of Christ myth that defined the new movement.

9 Wherefore God also hath highly exalted him, and given him a name which is above every name:10 That at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth; (Phil 2:9,10)

Actually I think these associations (akedah and Zechariah) would be a subsequent fleshing out of the Christ myth by those who reinterpreted the first narratives (“gnostic” descent from the unknown god) — that is by the “proto-orthodox” who were rewriting the myth so that the Christ was the fulfilment (not anithesis etc) of the Jewish Scriptures.

I have long sought for Christian origins in such fulfilment/allegorical interpretations of the Jewish Scriptures — I may need to re-examine all the thinking I have been doing in that quarter now.

Neil…The notion of a second power/son of God dying seems fundamental to ‘Christianity’. There is no doubt that Wisdom/Sophia had descended in Hellenized Jewish thought, but it/she never died afaik. There have been some good reviews of the Jewish evidence of a shift in focus upon Isaac’s role as submitting to sacrifice for the benefit of all Israel. If this factor too is pre-Christian why assume it was a later orthodox development?

I agree the existence of Gnostic forms so early requires a mystic origin but those few groups that denied the death of the Christ can be logically argued the result of misinterpretation of Mark (Simon Cyrene) or theological concerns about blasphemy.

If you take the Jesus of Christianity, remove the name Jesus, remove the death of a Son concept, remove the Descent of Wisdom/Sophia myth, remove the Messianic role, what is left?

I should have included, that I agree the overlay of the death having a direct correlation to the animal slaughter rite is strained. Theologians argue to this day by what mechanism the death of Jesus had value. Did blood pay for sins (very unJewish notion), did it pay a price/ransom? to who? (also unJewish) etc. In that regard, I agree the orthodoxy took a somewhat basic concept of mystically defeating death and sought an artificial analogy with animal rites, but misunderstood them in the process.

It’s a nonsensical, immoral and illogical notion that requires the most esoteric theological finesse to “comprehend”.

I am talking about Christian origins and the application of Jesus linked with the Isaac atonement is a “proto-orthodox” Christian idea. That the notion of Isaac’s blood being an atonement for Jews was a second temple idea among some Judeans (I do not believe there is any evidence that there was some unified Jewish idea about it). I have written about it at some length in many posts in the past: https://vridar.org/tag/akedah/ https://vridar.org/tag/binding-of-isaac/ but especially my posts on Levenson’s work: https://vridar.org/tag/levenson-the-death-and-resurrection-of-the-beloved-son/

My point about Christian origins, though, is that I am thinking that these arose in the context of proposing an antithesis or outright opposition to traditional Jewish interpretations. The higher, hitherto unknown god was not the god of the creator of the Jewish Scriptures. It was that higher god who sent his revealer or saviour figure to overcome the power of the Demiurge or “Jewish god”.

Subsequently, other “Christians” proposed to interpret that saviour god not as an opponent of the Scriptures or Jewish god, but as a fulfilment of the Scriptures and in partnership with that Jewish god. Some of them embraced interpretations that had been circulating about Isaac among Jewish sects in doing so. They may have come up with the interpretations independently or maybe were influenced by other Jewish akedah views.

I am not aware that the first “gnostics” actually denied the sacrifice of Jesus. I am looking at what is said about Saturninus in particular because he is one of the earliest we know about. He seems to have taught that the higher god, the one unknown and above the Jewish creator demiurge god, sent his son to die, to be crucified, in the way countless Jews had been crucified and demonstrated the failure of the Jewish god to save his people.

Just to clarify — I am not assuming it was a later development. I am thinking that an argument can be made that it makes sense, that it can most easily be explained, as a later orthodox development AMONG CHRISTIANS. The core of the idea was there in some Jewish circles beforehand, but the first opposition to Judaism opposed Jewish religion root and branch: it opposed the Jewish god and Jewish scriptures and Jewish law by proposing a higher god who sent a revealer to rescue Jews from that god and law and their scriptures. Such a “gnostic” religion would have disappeared without a trace an Christianity as we know it would never have been born had not some talented persons found a way to both reject the Jewish Bible and God as well as embrace it and ride with it — by reinterpreting that “gnostic” idea as a fulfilment, not an opposition, of the Scriptures. That proved to be a very powerful idea: sacred writings believed to have been very ancient were now rich with new meaning at the same time as the old Jewish religion was “dead and buried”.

I certainly would not give up on the first gospel Jesus being derived from the Suffering Servant.

I don’t think it is a contradiction that proto-dualism uses these scriptures while rejecting the Mosaic law. In the suffering servant they imagined the actions of a deity that was different to the one who gave the law and created the world.

I don’t think there is any evidence for ‘gnostics’ rejecting all scripture is there? They might use scripture differently, ie the snake is the hero etc

I suggest that the Ascension of Isaiah is a story about the suffering servant. It is also a teaching that hints at being anti-Mosaic. Isaiah is condemned for blasphemy against Moses for saying he saw the face of god but did not die.

I think it is interesting that ‘Isaiah’ means ‘God Saves’, the same as ‘Joshua’.

I think there is no need to throw away a perfectly decent hypothesis here. Dualism can still be rooted in old testament stories.

Isn’t the very idea of an unnamable Host High father of Yahweh also a preChristian Jewish idea? So that the identification of Christ as that ‘son’ (Yahweh) in the NT wasn’t a radically new idea. Even the Danielic Son of Man is identified with (as in emanation) the Ancient of Days in the OG LXX. It seems to me the only original ‘Gnostic’ idea was to offer an explanation for the condition of the nation and world by suggesting the demiurge wasn’t fit for the task and that rather than Christ being Yahweh, he was a replacement.

Forgive me, after letting it all sink in for a bit longer, maybe I now get your proposal. You’re suggesting rather than the orthodoxy representing a middle stage for a so-called Gnostic anti-Yahwist movement, there was a fringe Jewish sect that sought an explanation for the realities of the past and present, and reimagined their national deity and creator as deficient. Later, more tradition-centered Jewish Christians denounced that idea and rather identified Christ with the creator God of the OT (made easier by the disuse of the name Yahweh) and amplified the role of the Satan (also originally an agency of God but now called the ‘ruler of the world’) to explain the suffering.

Is that close?

I can’t see any obvious problems with that recreation. And it is possibly an explanation for the existence of Gnostic sects from the start.