When did the Exodus happen?

1 Kings 6:1

And it came to pass in the four hundred and eightieth year after the children of Israel had come out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel . . .

Solomon’s rule is said to have begun around 970 BCE. If we follow the 480 years reference in 1 Kings 6:1 then the Exodus took place around 1450 BCE.

When did the Israelites enter Egypt?

Genesis 15:13

Then He said to Abram: “Know certainly that your descendants will be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and will serve them, and they will afflict them four hundred years.

Exodus 12:40

Now the sojourn of the children of Israel who lived in Egypt was four hundred and thirty years.

Adding 400/430 years to 1450 brings us to 1880 to 1850 BCE.

The Hyksos Connection

Linking the Hyksos to the Israelites in Egypt

Hyksos is an Egyptian word meaning “foreign rulers”. The “Hyksos” entered Egypt along with Semitic groups from Canaan and even managed to rule northern Egypt from around 1670 to 1550 BCE. Their capital was Avaris in the Nile Delta.

One of the Hyksos kings was Y’qb-HR, or Jacob Har. Sounds familiar.

Josephus tells us that the third century BCE Egyptian “historian” Manetho referred to these foreign rulers in Egypt as shepherds. Josephus further identifies these Hyksos as the Israelites and cites the rule of Joseph over Egypt as support for this, and equates the eventual expulsion of the Hyksos with the Exodus of the Israelites.

How some scholars interpreted the above data

Some biblical scholars followed Josephus’ conjectures and argued that if this hypothesis is correct, it provides evidence of the “biblical version of the Hebrews sojourn in Egypt” (Orlinsky 1972, 52). In this view, when the native Egyptians overthrew the hated Hyksos and chased them out of Egypt, the Israelites lost their protectors and became enslaved, along with the remaining Semites in Egypt. Earlier biblical scholars had understood this situation as parallel to the biblical record: “Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph. . . . Therefore they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor” (Exod 1:8,11). (Wright, J. Edward, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher, “Israel In and Out of Egypt,” in The Old Testament in Archaeology and History, edited by Jennie Ebeling, J. Edward Wright, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher, p. 248. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2017)

Those scholars placed the Exodus, then, in the fifteenth century BCE (the 1400s BCE) just as the good book in 1 Kings 6:1 said.

The evidence for a Hyksos link to Israel’s Exodus

None. Neither archaeological nor biblical.

The evidence against a Hyksos link

Exodus 1:11

Therefore they set taskmasters over them to afflict them with their burdens. And they built for Pharaoh supply cities, Pithom and Raamses.

The building projects refer to the time of Pharaoh Rameses II who reigned from 1279 to 1213 BCE.

We don’t need to assume the reliability of that biblical claim but what we do have to accept is that its authors placed the Exodus event centuries after the time of the Hyksos. The same Rameses date is also centuries later than the date indicated by I Kings 6:1.

In the fifteenth century BCE Egypt was ruled by Pharaohs who are renowned for their extraordinary power: Thutmose III (1479-1425 BCE) and Amenhotep II (1427-1400 BCE) of the great Eighteenth Dynasty. These rulers repeatedly invaded Canaan.

There is no evidence that either lost control of Canaan to a massive Israelite invasion. Indeed, the book of Joshuas stories of the conquest of Canaan never even presents the Egyptians as opponents in battle. (Wright, Israel, 249)

-o0o-

Semites in Egypt

As early as Dynasty I the pharaoh had to defend Egypt’s borders and commercial interests in Sinai from troublesome Bedouin. An ivory label of King Den [see image on right] reads, “the first occasion of smiting Easterners.” From throughout the Old Kingdom reliefs have survived depicting pharaoh smiting Egypt’s enemies, and not a few of these have come from the Sinai. (Hoffmeier, James K. Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition, p. 54. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

“Asiatic” nomads (from Canaan and Syria) were always entering Egypt according to what we can read today from Egyptian scribes of the third and second millennium:

84. The east (Delta) abounds with foreigners . . .

91. Now speaking about these foreigners, as for the miserable Asiatic, wretched is the place where he is;

92. Lacking in water, hidden because of trees. Many and difficult are the paths therein because of mountains. He has not settled in one place.

93. Food causes his feet to roam about. He fights since the time of Horus. He does not conquer nor is he conquered.

94. He does not declare war, (but) is like a thief darting about in a group.99. Dig a canal to its … Flood its half to the Bitter Lakes. Look, it is a navel cord for the foreigners.

100. Its walls are warlike, its army numerous. The farmers in it know how to take up arms.

Hunger, drought, are said to push these Asiatics to go down into Egypt. The Egyptian pharaoh is said to have built a defensive canal and armed the local farmers to keep them out.

(It is not the only word that is translated as “Asiatic” in the Neferti prophecy.) |

He (Neferti) was concerned for what would happen in the land.

He thinks about the condition of the east.

Asiatics … travel with their swords,

terrorizing those who are harvesting,

seizing the oxen from the plow. . . .All happiness has gone away, the land is cast down in trouble

because of those feeders, Asiatics … who are throughout the land.

Enemies have arisen in the east, Asiatics have come down to Egypt. . . .One [= a pharaoh to come] will build the “Walls of the Ruler,” life prosperity and health,

to prevent Asiatics from going down into Egypt.

They beg for water in the customary manner

in order to let their flocks drink.

Drought (or need for water) drives the Semites (one of the words used for Asiatics) into Egypt. Fortifications are necessary to keep as many of them as possible out.

I reached the “Walls of the Ruler”

which were made to repulse the Asiatics,

to trample the Bedouin.

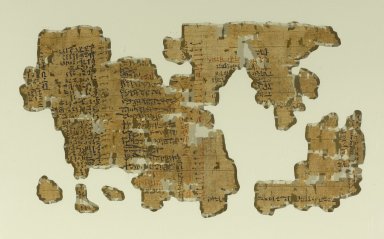

This papyrus lists the names of servants on an Egyptian estate: over 40 have Semitic names. That would indicate Semites were very populous in the Delta and northern region of Egypt. They are thought to have been descendants of earlier migrations, prisoners of war, slaves, traders and diplomatic tributes.

Egyptian records show that though many arrived as slaves or mercenaries, others worked as

scribes, draftsmen, butlers, goldsmiths, coppersmiths, musicians, builders, bodyguards of the pharaoh, physicians, and king’s messengers (Wright, Israel. p. 250)

And as shepherds:

There is evidence that Semites introduced sheep into Egypt during the Middle Kingdom (2133-1786 BCE) and that in the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE) they were employed as shepherds. (ibid, p. 249)

Archaeological evidence for Semites in Egypt

Tell el-Daba (= Avaris, the major Hyksos city; later capital of Rameses II, Pi-Rameses). Site contains

- Canaanite pottery;

- evidence of Syrian storm god, Baal Zaphon.

The domestic and religious architecture, burial traditions, ceramics, and bronzes all show strong connections to the Levant, although there was an increased Egyptianization of the pottery as time went on. Concerning the earliest Asiatic settlement, . . . Bietak concludes, “Donkey sacrifices in connection with tombs, and bronzes from the tombs reveal, however, in combination with the house-types that the inhabitants of this settlement were Canaanites, however, highly Egyptianized.” (Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt. p. 64)

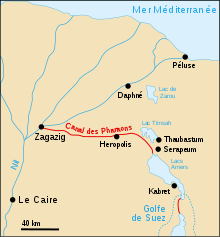

Wadi Tumilat

Of the seventy-one sites identified, twenty-one yielded Middle Bronze II, Levantine materials that correspond to the Second Intermediate through Hyksos Periods. Most sites are regarded as campsites or villages that were seasonally occupied by transhumants. . . . (ibid, p. 65)

Maskhuta

Excavations at Maskhuta from the late 1970s and early 1980s uncovered Middle Bronze, Canaanite remains. . . . The second phase witnessed more signs of permanence, such as mud-brick tombs with donkey burials and ceramics suggestive of the late Middle Bronze IIA and into IIB. . . . The people of this second phase have been labeled “Egyptian based’Asiatics.'” (ibid, p. 66)

Tell el-Retaba

Flinders Petrie had 1905 at Tell er-Retaba . . . exposed a fortress from the New Kingdom. Ramses II had built a temple there for the cult of “Atum as Lord of Tjeku”. A stele and statue show him with Atum. . . . During the time of the New Kingdom, the area was, among other things by the Shasu … used:

“The Shasu tribes of Edom (šʒśw n jdwm) passed through the fort of Merenptah in Tjeku to graze their cattle by the ponds of the Atum temple. I took her from Seth (3rd Heriu-renpet) on the day of her birthday to the place where the other Shasu tribes, who passed the fort of Merenptah in Tjeku days ago, have already arrived. Report of an Egyptian border official.” [Machine translation of Wikipedia article]

Tell el-Yehudiyeh

The sloped glacis on the outer edge of the tell, a common feature of Middle Bronze II sites from Syria through Canaan, led G. R. H. Wright . . . [to postulate] that the plastered glacis, otherwise unattested in Egypt, was a technique employed to protect a tell against weathering and erosion. If Wright is correct, then the presence of the glacis at this Delta site further ties it to the Middle Bronze Canaanite culture. About a kilometer east of the tell is the Second Intermediate Period cemetery. . . . The ceramic remains are of Palestinian type . . . (Hoffmeier, p. 67)

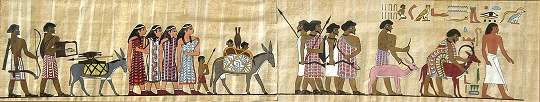

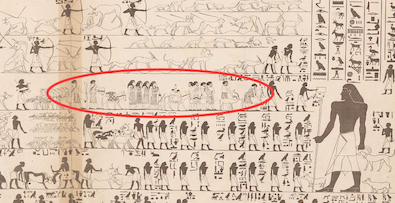

Tomb painting at Beni Hassan

The famous Beni Hassan scene and accompanying inscriptions report a caravan of 37 “Semites” (metalworkers and traders) visiting the governor in Egypt . . .

Apiru, and two eminent persons

We read of Apiru moving a stone at Pi-Rameses. Apiru appear frequently in the Amarna letters and other Egyptian sources as raiders and bandits in Canaan.

One Aper-el, a man with a clearly Semitic name (recall that “El” is the word for “god” in Semitic languages), attained the posi- tion of vizier, the most powerful position in the Egyptian royal court. Aper-el served during the Eighteenth Dynasty (1390-1336 BCE) under Amenhotep III and Akhenaten (Redmount 1998,102).

Much later, a Semite (perhaps Syrian?) named Bay was influential in placing an Egyptian on the throne during the late Nineteenth Dynasty (1295-1186 BCE). (Wright, Israel, p. 250 — my formatting and bolding)

Hoffmeier, James K. Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Newberry, Percy E. Beni Hasan. Part 1, London: Kegan Paul, 1893.

Wright, J. Edward, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher, “Israel In and Out of Egypt,” in The Old Testament in Archaeology and History, edited by Jennie Ebeling, J. Edward Wright, Mark Elliott and Paul V.M. Flesher, Waco: Baylor University Press, 2017.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Re: Beni Hasan

From Thompson’s 1974 publication of “The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives” p123 ff

“It has been commonly asserted that the [*people] pictured in tomb 3 at Beni-Hasan had come from Palestine or Transjordan…because of the identification of [*word] with Amorites of the Palestinian EB4/MB1 period and also because of the general effort to relate this painting as closely as possible to the biblical traditions….

The thesis that these people came from the Southern Transjordan …. is extremely weak, for not only is the reading of the place name in the Beni-Hasan painting uncertain but the biblical term is hardly more specific than a translation ‘sons of the desert’ would suggest……

In Egyptian the word [*word] is usually translated ‘dry’ or ‘desert’ ….ie the Eastern Desert of Egypt. At least, it is clear that the appearance of the name is not by itself adequate to justify so specific an identification as the place [*word] with Transjordan.

In any case an examination of the tomb painting in its context makes such an assertion completely untenable.

The text clearly points out that the reason for the entry of the people [*word] on this occasion was to bring galena…eye cosmetic, into Egypt.

Galena can be mined in the mountains bordering on the Red Sea both in Egypt and in southern Sinai….on the other hand, deposits are notably poor in Palestine, Syria and Arabia and these regions had to import [it]. Consequently black eye paint does not seem to have become common there until after 1400BC.

The suggestion that the people are travelling metal workers ..is based on what seems a fanciful identification of the strange object …on the back of the second donkey…as bellows ..is hardly justified. If the objects were bellows they would just have 2 handles on one end of the sack……

We are quite clearly told that the [the people] are involved in the very important Egyptian galena industry. We can then hardly look to Palestine or Transjordan for their place of origin.

Furthermore it needs to be stressed that the painting is from the tomb of the high Egyptian official [*name] the [*title]: Chnemhotep the “Administrator of the Eastern Desert in the town of Menat-Chufu”. The text relates that these [*people] entered Egypt and presented themselves to the official in charge of the border at or near Beni-Hasan.

If they had come from Palestine they would not have entered here in the south but by way of the Eastern Delta. The most obvious place to look for the homeland of the {*people] is the very Eastern Desert which Chnemhotep administered in the mountains along the Red Sea where galena is found……

From the inscriptions in the tomb of Chnemhotep’s grandfather, Chnemhotep 1 [tomb 14 at Beni-Hasan] we learn that Chnemhotep 1 had also been Administrator of the Eastern Desert ….

Other early texts which refer to [*people] adequately confirm the contention that they are to be seen as occupants of the Eastern Desert.”

{Refers to several other texts that mention “*people”]

“There is, at least in the texts we have seen so far, little basis from which one could argue that the [*people] in Egypt have come from any place other than the desert and highlands east of the Nile.”

Phew! I’m a lousy typist, that took a long time and I had to omit stuff too difficult to type. I hope it makes sense and is a fairly accurate rendition of Thompson’s very detailed and complex explanation.

Shorter Thompson – my paraphrase:

The people in the picture in tomb 3 at Beni-Hasan are Egyptian, not Semites from Palestine/Transjordan.

* Thompson uses a specific script here for the original writing – I can’t replicate that

PS This Beni-Hasan section is of particular interest to me because I identify strongly with the galena reference.

My father was a galena miner and I had some samples he gave me – its particularly beautiful stuff and one of the reasons I wanted to be a geologist when I grew. Didn’t happen.

Thanks for the additional info and clarification. The relevant inscription reads (according to https://archive.org/stream/benihasan00grifgoog/benihasan00grifgoog_djvu.txt),

As you point out, not all Semites were from Canaan or even the Levant, or if they were, they may well have travelled as traders through the mining areas of the Sinai.

Thanks Neil. Very informative. As with the actual existence of Jesus, we may never know the real truth or the origins of the tale. Given what we know of the movements of people in the eastern Mediterranean during the second millenium BCE, it is not surprising that there were numerous canaanites and other semites in Egypt throughout the period. That some were enslaved is similarly not surprising, or that there may have been a slave rebellion. And if that rebellion was local and small scale there may be no documentation of it. But the movement of the numbers of people described in Exodus, would have certainly attracted notice.

There may be a parallel with the much better documented captivity in Babylon in the 6th century BCE. Though described as the movement of the Jewish people, it was probably just a relatively small number of leaders who were removed, and a small number who returned. As with the Trojan war, it seems there was such a war, but that doesn’t mean the account in the Iliad is factual.

Some many historic records of the Egyptians cited – but believers keep telling me that the Egyptians didn’t record anything about the Jews because it was embarrassing. Of course believers don’t believe in history, they believe in myth.

Two things.

First, Josephus’ version of Manetho is suspected of containing interpolations that make the connection between Hebrews and the Hyksos. Even Eusebius, who had his own copy of Manetho, made clear when he was using Jospehus’ account of Manetho instead of the document he had. In other words, it appears that either (1) Josephus invented the connection, or (2) Josephus’ version of Manetho was corrupted.

Second, “Apiru” refers to refugees, displaced people without a home who took up banditry. They were not limited to a particular ethnic or class of people. Of course, that does not preclude semites from being among the Apiru.

It’s possible that an epithet could have been taken up as a badge of pride, especially for a gang of bandits.

May I ask what you do with the recent(-ish) religio-linguistic claims by the Christian Douglas Petrovich in your accounting of the Exodus?

Believing,

Felix Zamora

Would you like to tell us the evidence he claims in support of the Exodus?

Not knowing the details, I imagine I would probably do what critical scholars who rely upon valid methods of historical research do with any apologist who lets his faith decide how he will interpret the evidence.