Something is needed to break the impasse between the two sides:

Something is needed to break the impasse between the two sides:

Side 1: Matthew and Luke used both Mark and Q.

Side 2: There was no Q: Matthew used Mark and Luke used both Matthew and Mark.

One of the arguments against #2 is that it is inconceivable that Luke would have so thoroughly revised and restructured Matthew (especially the nativity story and the Sermon on the Mount) if he were using Matthew. Opposed to this argument is the claim that such a revision is not inconceivable. I tended to favour the latter.

So on that point the two sides cannot be resolved.

As I continue to read Delbert Burkett’s Rethinking the Gospel Source: From Proto-Mark to Mark I am wondering if the scales can be tipped in favour or one side after all. And what tips the balance? Silence. Roaring silence.

Before continuing, though, I need to apologize to Delbert Burkett for leaving aside in this post the central thrust of his argument. His primary argument is that neither the Gospel of Matthew nor the Gospel of Luke was composed with any awareness of the Gospel of Mark. Rather, all three synoptic gospels were drawing upon other sources now lost.

But for now I’m only addressing the question that Luke knew and decided to change much in the Gospel of Matthew.

Here is a key element of Burkett’s point :

The Gospel of Matthew has recurring features of style that are completely or almost completely absent from . . . Luke. Entire themes and stylistic features that occur repeatedly in Matthew are lacking in [Luke]. What needs explaining, then, is not the omission of individual words and sentences, but the omission of entire themes and recurring features of Matthew’s style. Since the great majority of these are benign, i.e., not objectionable either grammatically or ideologically, they are difficult to explain as omissions by either Mark or Luke, more difficult to explain as omissions by both. They are easily explained, however, as a level of redaction in Matthew unknown to either Mark or Luke. Their absence from Mark and Luke indicates that neither gospel depended on Matthew. (p. 43)

Details follow.

Words recurring in Matthew but not found in parallel passages in Luke

The word “then”, τότε

Used by Matthew 90 times.

Luke parallels 40 of passages in Matthew using τότε but Luke only uses τότε 7 times in those. 33 times he has avoided using Matthew’s τότε.

Not that Luke had an aversion to the word because he uses it in other passages as well, 21 times in Acts and 8 times in places in his gospel that do not parallel Matthew.

“Come to”, “Approach”, προσέρχομαι

Matthew uses this word 52 times. Even though 27 of those passages in Matthew are paralleled in Luke, the word appears only 5 times in those 27 passages. But Luke is happy to use the word 5 times elsewhere in his gospel and 10 times in Acts.

Example

Matthew 9:14 Then John’s disciples came and asked him, “How is it that we and the Pharisees fast often, but your disciples do not fast?

Luke 5:33 They said to him, “John’s disciples often fast and pray, and so do the disciples of the Pharisees, but yours go on eating and drinking.“

“Said”, ἔφη

Matthew uses it 16 times. Luke has 11 parallel passages to those but uses the word only once.

Not that he dislikes the word because he uses it elsewhere. It looks like he only objects to it if it is found in Matthew — if he indeed was using Matthew.

Example

Matthew 19:21 Jesus answered (ἔφη), “If you want to be perfect, go, sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

Luke 18:22 When Jesus heard this, he said (εἶπεν) to him, “You still lack one thing. Sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

“Called”, λεγόμενος

13 times in Matthew; 6 parallel passages in Luke but not one use of it in those passages. Luke does use it 4 times in other places, however.

Example

Matthew 27:33 They came to a place called (λεγόμενον) Golgotha (which means “the place of the skull”).

Luke 23:33 When they came to the place called (καλούμενον) the Skull

“From there”, ἐκεῖθεν

12 times in Matthew; 7 parallel passages in Luke in which ἐκεῖθεν is used a total of one time.

Example

Matthew 4:21 Going on from there (ἐκεῖθεν), he saw two other brothers, James son of Zebedee and his brother John.

Luke 5:10 and so were James and John, the sons of Zebedee, Simon’s partners.

“Withdraw”, “Depart”, ἀναχωρέω

10 times in Matthew; 4 parallels in Luke without using ἀναχωρέω

Example

Matthew 9:24 he said, “Go away (Ἀναχωρεῖτε). The girl is not dead but asleep.” But they laughed at him.

Luke 8:53 “Stop wailing,” Jesus said. “She is not dead but asleep.”

“Worship”, “pay homage”, προσκυνέω

Luke also uses this word but not when he is writing material that is parallel to Matthew and where Matthew uses it.

Example

Matthew 8:2 A man with leprosy came and knelt before (=worshipping) him . . .

Luke 5:12 A man came along who was covered with leprosy. When he saw Jesus, he fell with his face to the ground (not worshipping) . . .

Leave, Depart, Pass over, μεταβαίνω

6 times used by Matthew and 4 of these passages are paralleled in Luke but without use of the word. Luke does use the word in Acts 18:7 that does parallel the structure used in Matthew 12:9.

Example

Matthew 8:34 Then the whole town went out to meet Jesus. And when they saw him, they pleaded with him to leave (μεταβῇ) their region.

Luke 8:37 Then all the people of the region of the Gerasenes asked Jesus to leave them (ἀπελθεῖν), because they were overcome with fear. So he got into the boat and left.

Arrival, the coming, παρουσία

In the gospels this word is found only in Matthew. There are 4 parallel sections in Luke but no occurrences of the word.

Example

Matthew 24:3 “Tell us,” they said, “when will this happen, and what will be the sign of your coming (παρουσίας) and of the end of the age

Luke 21:7 “Teacher,” they asked, “when will these things happen? And what will be the sign that they are about to take place?”

Grammatical constructions recurring in Matthew but not found in parallel passages in Luke

Not only words but grammatical constructions are avoided by Luke when he is supposedly drawing on Matthew.

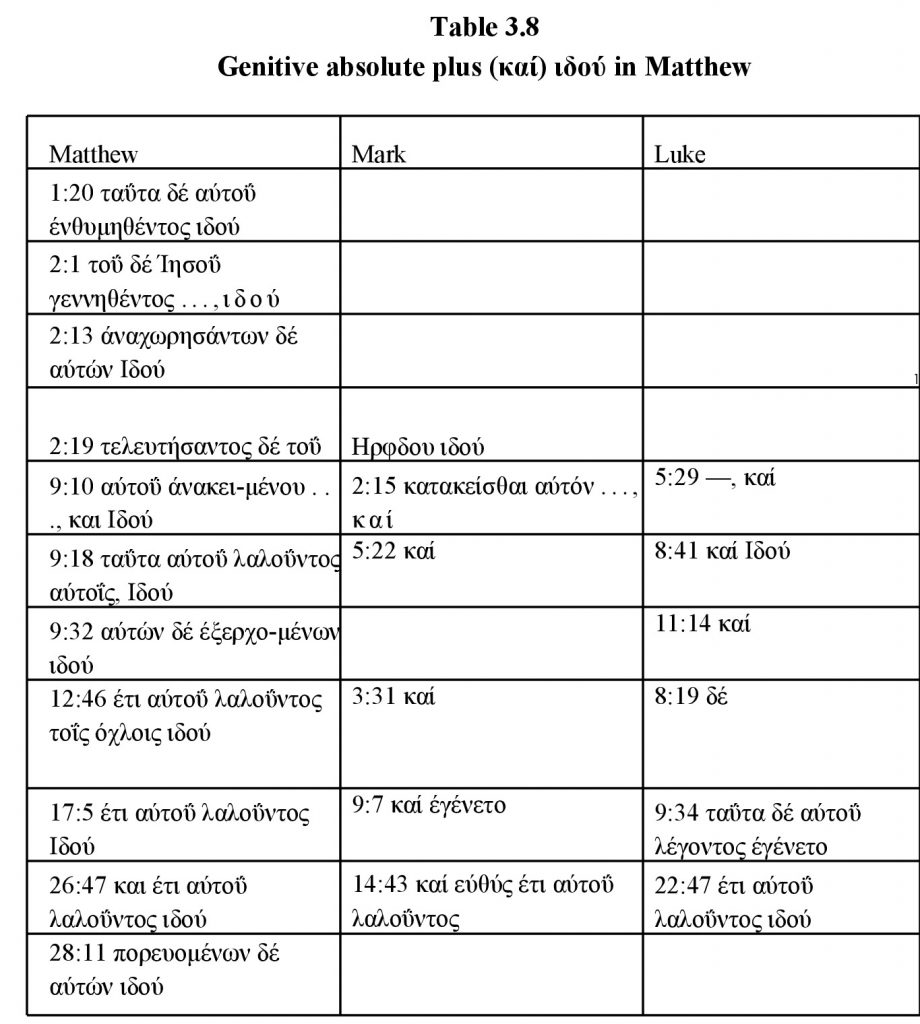

Not only words but also certain grammatical constructions recur in Matthew, such as a genitive absolute followed by ἰδοὺ or καὶ ἰδοὺ.

Matthew uses this construction 11 times. 6 of these passages are paralleled in Luke.

Only once does it occur in one of these parallels, in Luke 22:47 (compare Matthew 26:47) . . . . [T]his one instance [has been taken] as evidence that Luke used Matthew, since here a unique literary characteristic of Matthew appears in Luke. However, to call this a “unique” characteristic of Matthew overstates the case, since it occurs elsewhere in Acts 1:10. . . . On the contrary, when we stop focusing on a single passage, the whole picture presented by Table 3.8 suggests just the opposite. Luke 22:47 and Acts 1:10 show that Luke had no aversion to the construction. Why then, given the theory that Luke used Matthew, did he almost always eliminate it when he found it in Matthew? (p. 53)

The table shows that Luke used Matthew’s phrase once out of the six times he paralleled Matthew’s material.

Phrases recurring in Matthew but not found in parallel passages in Luke

- Matthew 1:22 All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet

- (Matthew 2:5 for this is what the prophet has written — spoken by Herod’s advisors)

- Matthew 2:15 And so was fulfilled what the Lord had said through the prophet

- Matthew 2:17 Then what was said through the prophet Jeremiah was fulfilled

- Matthew 2:23 So was fulfilled what was said through the prophets

- Matthew 4:14 to fulfill what was said through the prophet Isaiah

- Matthew 8:17 This was to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet Isaiah

- Matthew 12:17 This was to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet Isaiah

- Matthew 13:35 So was fulfilled what was spoken through the prophet

- Matthew 21:4 This took place to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet

- Matthew 26:56 But this has all taken place that the writings of the prophets might be fulfilled

- Matthew 27:9 Then what was spoken by Jeremiah the prophet was fulfilled

Yet even though Luke liked the idea of fulfilled scripture he never once uses such a phrase. This failure adds support to the view that he did not know of Matthew.

Another

- Matthew 4:23 . . . . healing every disease and sickness among the people

- Matthew 9:35 Jesus went through all the towns and villages, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom and healing every disease and sickness.

- Matthew 10:1 Jesus called his twelve disciples to him and gave them authority to drive out impure spirits and to heal every disease and sickness.

Contrast Luke where he parallels two of the above passages:

- Luke 12:1 After this, Jesus traveled about from one town and village to another, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God. The Twelve were with him.

- Luke 9:1 When Jesus had called the Twelve together, he gave them power and authority to drive out all demons and to cure diseases.

Not, similarly, the phrase Matthew likes to use at the end of each narrative discourse by Jesus. Luke does use the same phrase once at the end of his Sermon on the Plain where Matthew used it at the end of the Sermon on the Mount, but after that, Luke decides not to use it anymore.

Matthew 7:28 When Jesus had finished saying these things, the crowds were amazed at his teaching

Luke 7:1 When Jesus had finished saying all this to the people who were listening, he entered Capernaum.

Matthew 11:1 After Jesus had finished instructing his twelve disciples, he went on from there to teach and preach in the towns of Galilee.

Luke 9:5 If people do not welcome you, leave their town and shake the dust off your feet as a testimony against them.

Luke 10:16 “Whoever listens to you listens to me; whoever rejects you rejects me; but whoever rejects me rejects him who sent me.”

Matthew 13:53 When Jesus had finished these parables, he moved on from there.

Luke 8:18 Therefore consider carefully how you listen. Whoever has will be given more; whoever does not have, even what they think they have will be taken from them.”

Matthew 19:1 When Jesus had finished saying these things, he left Galilee and went into the region of Judea to the other side of the Jordan.

Matthew 26:1 When Jesus had finished saying all these things, he said to his disciples

Luke 21:36 Be always on the watch, and pray that you may be able to escape all that is about to happen, and that you may be able to stand before the Son of Man.”

Matthew’s recurring redactional insertions not found in parallel passages in Luke

Matthew has a habit of making insertions or interpolations into his source material. Two illustrations:

Matthew 9:13 On hearing this, Jesus said, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. But go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.‘ For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.”

Matthew 12:7 I tell you that something greater than the temple is here. If you had known what these words mean, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice,’ you would not have condemned the innocent. For the Son of Man is Lord of the Sabbath.”

The bolded sentence breaks the logical flow of the surrounding material. Matthew liked the idea of mercy trumping sacrifice so much he forced his way into using it twice. No-one can deny that Luke also liked the principle of mercy being more important than sacrifice (just recall his parable of the Good Samaritan) so it must be considered odd that he did not adapt Matthew’s words had he known them.

Delbert Burkett cites many other examples (over 50 in fact) to make his case.

As I think about not so much each one of the above but such thorough absence of recurring characteristics of Matthew’s style I do confess that I am feeling strongly obligated to let go of my preference for Luke making use of Matthew’s gospel.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

A re-post of an old comment I made here based on the ideas of Mike Goulder and the use of imagery.

Different authors have different ‘signatures’ in the way they wrote.

Authors are identifiable by the characteristics of their prose style.

Among style aspects Goukder looked at was imagery, as used by ‘Matthew’.

And specifically the use of ‘animal imagery’.

Here are 10 such he looked at.

“Give not what is holy to dogs, and cast not your pearls before swine.

Or he asks for fish, will he give him a snake?

Who comes to you in sheep’s clothing, but inward are ravening wolves.

Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests.

I am sending you out as sheep in the midst of wolves.

So be as wise as serpents and innocent as doves.

You strain at a gnat but swallow a camel.

You snakes, you brood of vipers!

As a hen gathers her chicks under her wings.

As a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats.”

Goulder’s comment:

“The gospels are full of imagery, but one striking set of images is animals; and we find that animal images often occur in pairs, the animals frequently being in some way symbolic. There are 10 such pairs in the gospel tradition.”

And then he noted that:

-all 10 are in “Matthew”

-none are in ‘Mark’, ‘special’ ‘Luke’ or ‘John’.

I took it that he identified the use of this imagery as characteristically ‘Matthean”.

Individual to and a signature of the author called ‘Matthew”.

And he noted that:

” 3 recur in Q passages in ‘Luke”.

Concluding that Q was “Matthew”, as in “Luke” having sourced those images from the text of ‘Matthew” and this [and other] common material was later labelled ‘Q’ according to that speculation, which Goulder did not share.

I’ve mostly leaned in Goulder’s direction because of arguments like the one you set out. Burkett has taken a contrary approach and instead of looking at features in common is looking at what’s missing. That sounded at first like a non-starter to me at first, but it’s got me (re)thinking, as you can see.

I want to see someone make the reverse analysis. Were there common Lukan words and expressions that do not occur in the Matthean parallels even though Matthew uses them elsewhere?

If the answer is yes, then I suppose Q is back on the table.

If the answer is no, then Matthean posteriority starts looking pretty good.

Similarly, the pericopes shared by Mark and Luke, but not Matthew, should be analyzed in this fashion.

Have you checked out Robert K. MacEwen’s book on Matthean Posteriority and Alan Garrow’s papers on his “Matthew Conflator Hypothesis”? See here: http://www.alangarrow.com/synoptic-problem.html

It’s on my “to read” list.

I find Garrow’s arguments very strong, especially when combined with Klinghardt’s – that Matthew drew on an early version of “Luke” (the Marcionite Evangelicon). The two-source hypothesis may have worked well with a more limited body of data, and served to eliminate the Griesbach hypothesis (until chiastic analysis really finished it off) but I think it should be a given today that the known gospels’ inter-relationships are far more complex than can be explained on the assumption that the canonicals (in the forms we now have them) existed prior to all but one unattested “source”. Just the “rule-of-thumb” that one canonical synoptic came about a decade after the last seems to play against the assumption that Matthew didn’t know Luke, never mind the apologetic assumption that Luke would give Matthew a higher status than any other of the sources he indicates in the prologue.

I doubt the field will advance much until NT scholars acknowledge that the canonicals as we know them are a late, arbitrary category of a much broader field of literature.

I think that Matthean Posteriority also fails to explain key pieces of the evidence, namely the evidence for conflation in Mark. This topic is covered in Chapter 6 of Burkett’s book. He uses this as an argument against the two-source hypothesis and the Farrer hypothesis, but I think his argument also works as an argument against Matthean Posteriority.

Here is a lengthy excerpt from Chapter 6 that shows how the argument goes:

If I understand correctly, Burkett seems to be arguing that because parts of the Matthean redaction are “benign” (i.e. “not objectionable either grammatically or ideologically”) Luke should not have had any objection to using them. But, as Burkett acknowledges, redaction passages often bear the stamp of the redactor and that is the case here with Matthew, i.e., much of his redaction displays a recognizable Matthean style. So couldn’t that itself be a reason Luke would avoid slavishly copying it? That is, if Luke did use Matthew, should we assume that he would not have cared if any of his readers realized he had lifted much of his material from that source? I’m not so sure. I’m not sure he would have wanted to give any such implicit recognition or status to Matthew’s work. And if not, he would have had to make sure Matthew’s distinctive voice didn’t get into his gospel.

If I understand correctly, Burkett assumes that Luke was more a careful compiler of source material than a creative writer. So for him the absence of Matthean style from Luke means that Luke likely drew from some other source(s). As is so often the case with Synoptic comparisons, our assumptions are a big factor. The question becomes: which assumptions are more plausible?

Yes, similar objections crossed my mind as I was reading that chapter but I was compelled to apologized to Burkett for covering only one part of his argument. Two points count against the objection, I think:

1. Many of the words are not alien to Luke’s style; he appears to avoid them only when they are found in Matthew. Okay, let’s imagine he is hyper-sensitive to appearing to follow Matthew (though I have to wonder if avoidance of τότε really cuts it) — so we have the next point. . . .

2. The same phenomenon we see in Luke’s relationship to Matthew is likewise found in Mark’s relationship to Matthew.

But now we’re saying, But, but — aren’t we talking about Matthew’s redaction of Mark?!

I am no longer convinced that we are. Chapter 1 undermined my longstanding confidence that Matthew did redact Mark.

So I can only return to my mea culpa and stress that I have only presented one slice of Burkett’s argument here. My excuse is that I have personally “really liked” the Farrer hypothesis and so questioning it at this stage in this way is generating something of a minor trauma in my head.

There is more to the larger argument that I have not yet even touched on in this comment.

Maybe I should try to do a post on his chapter 1 sooner rather than later.

“Many of the words are not alien to Luke’s style; he appears to avoid them only when they are found in Matthew.” I’ve heard this brought up in defense (somehow) of Luke’s ignorance of Matthew; it seems to me indicative that Luke just wanted to avoid sounding too much like Matthew – perhaps because he was more concerned with adapting (co-opting and “updating” with additional sources) the Evangelicon for Catholicism.

“Chapter 1 undermined my longstanding confidence that Matthew did redact Mark.” Looking forward to those arguments; do you just mean that Mt drew from (an) intermediary gospel(s), rather than directly from Mk?

Burkett argues that all three of the Synoptics drew from earlier sources that are now lost.

On page 5, he writes:

In my own study of the problem, I too have concluded that the simpler theories do not work. No one Synoptic served as a source for either of the other two. All theories of Markan priority, Matthean priority, and Lukan priority thus start from a wrong premise. I base this conclusion in part upon the history of the discussion and in part on new data that will be presented in this book. This data calls into question all theories of mutual dependence and suggests instead that all three Synoptics drew on a set of earlier written sources that have been lost.

That seems absurd to me as a storyteller – considering Mark’s rigid narrative structure, of which only indiscriminate fragments remain in the other synoptics. It’s like looking at a popular poster, and a couple of collages based on it: there’s no question which came first, or whether two of them were somehow based on the first. Lost sources may sometimes be reasonable hypotheses, but trying to explain everything away with them (as the two-source also does) just compounds the issues.

Burkett builds a detailed, cumulative argument that leads step-by-step to the conclusion that the simple theories (two-source, Farrer-Goulder-Goodacre, neo-Griesbachian, etc.) are probably incapable of explaining the features that are found in the synoptics in a reasonable manner.

After having carefully read the first six chapters of his book, I think that his arguments are quite strong.

Required reading on the subject of Q.

http://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/1903/1378/umi-umd-1380.pdf;jsessionid=C40F3B4085495B570EC9B43302F94496?sequence=1

“HOW LUKE WAS WRITTEN”

Kenneth A. Olson

Thank you so much for reviewing Delbert Burkett! I am so glad that his Multi-Source Hypothesis is finally seeing some light!

This is only the tip of the iceberg. Burkett postulates six lost sources: A, B, C, Proto-Mark, Proto-Mark A, and Proto-Mark B. The proofs show that the sources were used in the correct order but that the authors kept switching between one source to the next, leaving behind traceable routes of textual reproduction.

http://lost-history.com/images/gospel-chart.jpg

When an author was copying from multiple texts wasn’t the normal practice to follow one as the primary template with lesser inputs from others? (I don’t recall off-hand the studies I believe I read some time back making that point — one which seemed very reasonable given the natural limitations involved even for us when copying from multiple sources.)

Does not Burkett’s hypothesis in one sense become weaker as more sources are proposed? Is he suggesting that there was no one source followed as the primary focus with secondary glances at the others?

I am not yet half-way through his book (books like this I take slowly as I try to be sure I take in each step in detail) but one question I am waiting to ask up ahead is how much room, if any, Burkett allows for authorial invention.

I am not sure if sprinkling additions onto a core text is more common than even combinations. Regarding Burkett’s hypothesis, I would say once Proto-Mark was written, that became the “primary focus” for the authors of Proto-Mark A and Proto-Mark B, with the earlier A, B and C sources being used as “secondary glances”.

When I read critics of the Two Source Hypothesis prattle on about “Occam’s Razor”, I always think about how they would probably hate Burkett even more. In a sense, yes, a hypothesis does become weaker the more sources you add to it because the more complicated a hypothesis is, the more chances there are for you to be wrong about something, but if the problem is itself complicated, then a complicated answer will at least be closer to the correct answer than the simple answer, and any analysis of the Synoptic Problem shows it is in fact a very complicated problem.

Proponents of Farrer think they can answer a complicated problem with a simple answer, but the questions about why the textual replication process became so complicated for such a simple model are never adequately explained. The “entropy” within the puzzle is not solved but is just delegated to the unfathomable mind of the author: Why did Luke jump around dozens of times like that if he was just copying from Mark and Matthew? “Who knows. People do crazy things.”

That’s why I think the Two Source Hypothesis is a far better than Farrer: it actually provides good technical answers for a large number of the particularly weird complications about the Synoptic Problem. It probably only answers something like 75% of the textual problems regarding why the author jumped around, but that’s better than just brushing them off as incomprehensible fancies of the copyist. The real problems for Two Source Hypothesis advocates come when they try to smooth over the “minor agreements” by introducing absurd ideas like Q3, where John the Baptist references are somehow added to a Sayings Source.

As silly as it may seem that each of the gospel writers had something like 3 to 6 sources sprawled out around them as they wrote, Burkett’s Hypothesis actually provides an explanation for 95% of the textual problems with jumping around: the authors were not jumping back and forth within one source text for no apparent reason but were jumping between sources so as to combine smaller gospels into larger and larger gospels. Using Burkett’s graphs, you can see that the creation of the gospels were far more systematic and linear than either Farrer or Two Source Hypothesis advocates ever dreamed possible.

Having just finished Burkett’s newer 2018 volume, I find it “interesting” that he defends a general “proto-Mark” but almost not at all specifically defends a “Proto-Mark A AND Proto-Mark B.” I think he was pushing Occam’s Razor, BUT …. he never explicitly rejects the two different proto-Marks idea in this book, either.

Anyway, I’m not convinced. I’d give 10 percent probability to a general single proto-Mark. None to his original idea of two.

I don’t find the argument based on “Words recurring in Matthew but not found in parallel passages in Luke” very convincing, although Burkett appears to produce an impressive list (I haven’t read his book). In each individual example, I find that it doesn’t support Burkett’s conclusion, viz. that “they are difficult to explain as omissions by … Luke”

Some examples:

– The word “then”, τότε. Matthew uses τότε 90 times, which is an awful lot. Mark uses τότε only 6 times, John only 10! I would say that τότε is a typical Mathean expression (like the ‘gnashing of teeth”). Even if Luke knew Mathew, it is NOT difficult to explain that Luke didn’t use this typical Mathean phrase. In the same vein, both Mathew and Luke avoided the word ‘kai’, which Mark uses an awful lot (with meaning similar to τότε). For a good example, compare Mark 4:39, Matt 8: and Luke 8:24. Luke uses the word τότε as frequently in parallel passages as he does in other passages.

– προσέρχομαι: Mathew ‘overuses’ the word 49 times. Similar reasoning as τότε: Mark uses προσέρχομαι only 5 times, John only once!. Mathew uses προσέρχομαι more frequently then all the other texts in the NT together (36 times). Luke uses the word as frequently in parallel passages as he does in other passages.

– ἔφη: Matthew 11, Luke 8 times. Here, at first sight, it does appear that Luke uses the word less frequently in parallel passages. However, this difference can also be due to Luke’s superior mastery of the Greek language: in passages where ‘to say’ occurs more than once, Luke uses 2 different words for ‘to say’. E.g. Luke 22:70, Luke 5:24 a/o. When we take these ‘improved’ sentences out, then little remains of a frequency difference.

– λεγόμενος: I could find only one occurrence of λεγόμενος in Luke, viz. naming Judas. Mathew also use λεγόμενος to name Judas. Hence, no support for Burkett’s theory that Luke doesn’t use Matthew’s words. I couldn’t find a single instance of λεγόμενον in Luke, hence we can’t derive a conclusion for this word about its frequency in parallel paragraphs.

– ἐκεῖθεν: Luke uses the word only 3 times, including once in a parallel paragraph. This is even more frequently then expected on the overall frequencies of use of ἐκεῖθεν in Mathew and Luke!

– ἀναχωρέω: Luke doesn’t use the word at all (Mark only once) hence we can’t derive a conclusion for this word about its frequency in parallel paragraphs.

This is where I ended my plenary assessment, but I expect the other words to have similar effect: these are words that are particularly favoured by Mathew (against the other 3 evangelists), so it is really not strange that they are not always used in parallel paragraphs. In fact, the frequency in parallel paragraphs is similar to the overall frequency in Luke’s gospel.

Hence, Burkett’s argument reduces to the observation that Luke does NOT use words in the parallel paragraphs that he doesn’t use elsewhere either. This is only meaningful if Burkett assumes that Luke would copy Mathew verbatim: but we already know that Luke doesn’t copy Mark (or Q) verbatim, nor does Mathew (or John…)!

The story of the “unclean spirit” Matt. 17:14 // Luke 9:38 is the more original version of the story. If you remove all of the text unique to Mark 9:17-27 in his version of the story, you get a relatively complete internally consistent story. This suggests that Mark 9:14-27 has conflated the story of the “unclean spirit” that throws a boy into the fire and water with a different story about an “unspeaking and mute spirit” whose father begs Jesus to help his unbelief. This is shown by the fact that a crowd forms in Mark 9:25 despite there already being one in 9:17. The unique story that Mark conflates centers on the faith of the father while the common story centers on the faith of the disciples. Mark’s unique story offers a climax in 9:26 where the reader is led to believe that the child may have died before a twist ending where Jesus pulls him up, showing the child to be both alive and cured, but the effect is ruined because the conclusion from the common story informs the reader beforehand that the spirit had left him and that he had been cured. This conflation is further evidenced by the fact that Mark 9:14-16 uses a very high concentration of characteristic Markan language (“around them”, “arguing”, “immediately”, “they were astounded”, “running forward”, “they greeted”, “he asked”, “around you arguing”) that both Matthew and Luke omit. These words are used by Matthew and Luke in non-Markan contexts so there is no reason to believe that Matthew or Luke disliked these words and chose to edit them out all 24 times that Mark uses them. This suggests that all three Synoptic gospels used now lost source(s).

Mark also conflates miracle story elements that are found only in Matthew with miracle story elements that are found only in Luke:

Mark 1:32: “When evening came [Matt. 8:16], when the sun set [Luke 4:40], they were bringing to him all the ill and the demonized [Matt. 4:24; 8:16]. And the whole city was gathered at the door. And he healed many ill with various diseases. And he cast out many demons. And he did not allow the demons to speak, because they knew him [Luke 4:41].

Mark 1:42: “The leprosy left him [Luke 5:13] and it was cleansed [Matt. 8:3].”

Mark 3:7: “And Jesus with his disciples [Luke 6:17] withdrew [Matt. 12:15] to the sea [Luke 5:1]. And a large crowd followed from Galilee [Matt. 4:25; Luke 5:17] and from Judea and from Jerusalem [Matt. 4:25; Luke 5:17, 6:17] and from Idumea and across the Jordan [Matt 4:25] and around Tyre and Sidon [Luke 6:17]. A large crowd, hearing what he was doing, came to him [Luke 5:1, 6:18]. And he told his disciples that a boat should wait for him because of the crowd, lest they crush him [Luke 5:3]. For he healed many, with the result that those who had afflictions would fall upon him that they might touch him [Luke 6:19]. And the unclean spirits when they saw him, fell before him and cried out saying, “You are the Son of God.” [Luke 4:41]. And he ordered them repeatedly not to make him known [Matt. 12:16; Luke 4:41].”

Mark 6:30: “And the apostles gather to Jesus. And they reported [“apangello”; Matt 14:12] to him all the things they had done [Luke 9:10] and the things they had taught. And he says to them, “Come, you privately [Luke 9:10], to a deserted spot and rest for a little.” For there were many coming and going and they did not have time even to eat. And they went away in the boat to a deserted spot privately [Matt 14:13].”

Mark 6:33: And they saw them going and many found out [Luke 9:11]. [“The crowds followed them.” -Matt. 14:13, Luke 9:11.] And on foot from all the cities [Matt. 14:13] they ran together there and preceded them. And getting out he saw a large crowd and felt compassion for them [Matt 14:14], because they were like sheep without a shepherd. And he began to teach them many things [~Luke 9:11]. [“And he healed their sick” -Matt 14:14; Luke 9:11.]

Mark 8:37: “A great [Matt. 8:24] storm of wind [Luke 8:23] came up, and the waves broke into the boat [Matt. 8:24] so that the boat was already filled up [Luke 8:23].”

Mark 5:2: “When he got out of the boat, immediately a man from the tombs [Matt. 8:28] with an unclean spirit met him, and he had his dwelling in the tombs [Luke 8:27]

Mark 5:12: “Send us into the pigs [Matt 8:31], so that we may go into them [Luke 8:32].”

Mark 5:28: “For she said, ‘If I touch even his garments, I will be healed [Matt. 9:21]. And immediately the fount of her blood dried up [Luke 8:44].”

Mark 5:30: “Turning around in the crowd [Matt. 9:22], he said ‘Who touched my garments?’ [Luke 8:45]”

Mark 5:34: “Go in peace [Luke 8:48], and be healed of your affliction [Matt. 9:22].”

Mark 5:38: “And he sees an uproar [Matt. 9:23] with people weeping and grieving greatly [Luke 8:52].”

Mark 5:37: “And he did not let anyone follow with him except Peter, James, and John… [Luke 8:51]. Throwing everyone out [Matt. 9:25], he took along the father and mother of the child [Luke 8:51].

Also:

*The world “polus” (“much”) is used 58 times, of which Matthew fails to copy the word or material 76% of the time and Luke fails to copy it 84% of the time.

*Of the 13 times that Mark talks about Jesus looking around, the crowd moving around Jesus, Matthew omits all 13 and Luke omits 11. (3:5, 3:32, 3:34, 4:10, 5:32, 6:6, 6:36 9:8, 9:14, 10:23, 11:11, 3:32, 3:34)

*Matthew and Luke both omit all 9 instances where Mark uses the phrase “he began to teach”, “he taught them”, or “in his teaching”.

*Matthew and Luke both omit all 7 instances in which Jesus is trying to get privacy from crowds that are so large they interfere with normal activities. (1:33, 1:45, 2:1, 3:20, 6:31, 7:24, 9:30)

So is the genitive absolute followed by ἰδοὺ or καὶ ἰδοὺ an indicator for Luke – not – knowing Mathew? Burkett lists in his Table 38 where this construction occurs in Mathew. But note that the first 4 of these occur in the infancy narrative, which is unique to Mathew. Hence, to list in the table that Luke doesn’t use the genitive absolute followed by ἰδοὺ or καὶ ἰδοὺ is meaningless for those 4 cases. The story of Mathew 28:11 (about the guards) is also absent in Luke (and Mark), hence also a meaningless entry in the table.

The table shows that Mathew uses the genitive absolute followed by ἰδοὺ or καὶ ἰδοὺ a lot more often than Luke (or Mark). Its use adds drama to the narrative. “Lo”, “behold”! We find the genitive absolute frequently in the LXX (eighty-three times in Genesis alone!), so Mathew may be giving his gospel a ‘pentateuch’ feel by using it too.

Mathew uses the genitive absolute when his narrative is interrupted by external events. Mark has only one external disruption, and both Mathew and Luke preserve the genitive absolute followed by ἰδοὺ or καὶ ἰδοὺ there. Luke doesn’t seem to use this style figure with ἰδοὺ or καὶ ἰδοὺ elsewhere at all. Since its use is reminiscent of the LXX and Mathew, I don’t find that “they are difficult to explain as omissions by … Luke”. It is a matter of Luke’s Christological intent and writing style.

Already Émile Boismard and Philippe Rolland, conservative Catholic scholars, discovered, long before Burkett, the necessity of multiple common sources for the synoptics.

Starting from Rolland’s, Jean Magne provided about thirty years ago the first JesusMyth-friendly version of the multiple-source route, concentrating on the last supper and the feeding miracles.

Independant from any French influence, Stuart Waugh gives, however, the most consequently critical multi-source explanation on his blog http://sgwau2cbeginnings.blogspot.com/