I expect this post will conclude my series challenging Richard Carrier’s arguments in On the Historicity of Jesus attempting to justify the common belief that early first century Judea was patchwork quilt of messianic movements. This belief has been challenged by specialist scholars* (see comment) especially since the 1990s but their work has still to make major inroads among many of the more conservative biblical scholars. We have seen the Christian doctrinal origins of this myth and I discuss another aspect of those doctrinal or ideological presumptions in this post. Carrier explicitly dismissed three names — Horsley, Freyne, Goodman — who are sceptical of the conventional wisdom, but I think this series of posts has shown that there are more than just three names in that camp. Many more than I have cited could also be quoted. Their arguments require serious engagement.

Richard Carrier sets out over forty social, political, religious and cultural background factors that anyone exploring the evidence for Christian origins should keep in mind. This is an excellent introduction to his argument, but there are a few I question. Here is one more:

(a) The pre-Christian book of Daniel was a key messianic text, laying out what would happen and when, partly inspiring much of the very messianic ferver of the age, which by the most obvious (but not originally intended) interpretation predicted the messiah’s arrival in the early first century, even (by some calculations) the very year of 30 ce.

(b) This text was popularly known and widely influential, and was known and regarded as scripture by the early Christians.

(Carrier 2014, p. 83, my formatting and bolding in all quotations)

The current scholarly approach to the origins of Christology has been guided by the apocalyptic hypothesis. The apocalyptic hypothesis is that Jesus proclaimed the imminence of the kingdom of God, a reign or domain ultimately imaginable only in apocalyptic terms. Early Christians somehow associated Jesus himself with the kingdom of God he announced (thinking of him as the king of the kingdom) and thus proclaimed him to be the Messiah. If Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet, as the logic seems to have run, it was only natural for early Christians to conclude that he must have been the expected Messiah and that it was therefore right to call him the Christ.

With this hypothesis in place, the field of christological “background” studies has naturally been limited to the search for “messianic” figures in Jewish apocalyptic literature.2

…..

2. A theological pattern has guided a full scholarly quest for evidence of the Jewish “expectation” of “the Messiah” that Jesus “fulfilled.” Because of the apocalyptic hypothesis, privilege has been granted to Jewish apocalyptic literature as the natural context for expressing messianic expectations. The pattern of “promise and fulfillment” allows for discrepancies among “messianic” profiles without calling into question the notion of a fundamental correspondence. Only recently has the failure to establish a commonly held expectation of “the” Messiah led to a questioning of the apocalyptic hypothesis.

(Mack 2009, pp. 192-93)

Part (b) is certainly true. Part (a), no, not so. The apocalyptic book of Daniel was popular but it was not a key messianic text.

The book of Daniel was a well known apocalyptic work but most apocalyptic literature of the day contained no references to a messiah. Apocalypticism and messianism are not synonymous nor even always conjoined. Messiahs were not integral to the apocalyptic genre. It was more common in apocalyptic writings to declare that God himself would act directly, perhaps with the support of his angelic hosts. Very few such texts contain references to a messiah. Even when reading Daniel you need to be careful not to blink lest you miss his single reference to an anointed one (messiah). And even that sole reference, as we learn from the commentaries and to which Carrier himself alludes, is a historical reference to the high priest Onias III. There is nothing eschatological associated with his death.

Yes but, but ….

…. Didn’t the Jews in Jesus day believe that that reference was to a messiah who was soon to appear?

This is where a search through the evidence might yield an answer.

The evidence supporting “this fact”?

According to Carrier there is an abundance of evidence supporting “this fact” — by which he appears to mean both parts (a) and (b) in the above quotation.

This fact [i.e. a+b] is already attested by the many copies and commentaries on Daniel recovered from Qumran,45 46 but it’s evident also in the fact that the Jewish War itself may have been partly a product of it. As at Qumran, the key inspiring text was the messianic timetable described in the book of Daniel (in Dan. 9.23-27). (pp. 83-84) . . . .

. . . .

45. See Carrier, ‘Spiritual Body’, in Empty Tomb (ed. Price and Lowder), pp. 114-15, 132-47, 157, 212 (η. 166). The heavenly ascent narrative known to Ignatius, Irenaeus and Justin Martyr (see Chapter 8, §6) may have alluded to this passage in Zechariah, if this is what is intended by mentioning the lowly state of Jesus’ attire when he enters God’s heavenly court in Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 36.

46. On the numerous copies of Daniel among the Dead Sea Scrolls, including fragments of commentaries on it, see Peter Flint, ‘The Daniel Tradition at Qumran’, in Eschatology (ed. Evans and Flint), pp. 41-60, and F.F. Bruce, ‘The Book of Daniel and the Qumran Community’, in Neotestamentica et semitica; Studies in Honour of Matthew Black (ed. E. Earle Ellis and Max Wilcox; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. 1969). pp. 221-35.

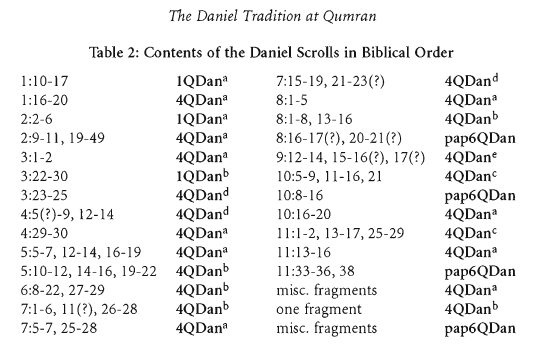

I suspect some oversight at #45 because I am unable to locate a related discussion in Empty Tomb. So on to #46. I don’t have Bruce’s book chapter but I do have Peter Flint’s. Here is his chart setting out the Daniel texts in the Qumran scrolls (p. 43):

Notice what’s missing, apart from any certainty regarding Daniel 9 as explained in the side-box. There is no Daniel 9:24-26. No reference to the anointed one. (We might see a flicker of hope with those few verses from chapter 9 in that table but sadly Flint has this to say about those:

Notice what’s missing, apart from any certainty regarding Daniel 9 as explained in the side-box. There is no Daniel 9:24-26. No reference to the anointed one. (We might see a flicker of hope with those few verses from chapter 9 in that table but sadly Flint has this to say about those:

However, the eighth manuscript, 4QDane, may have contained only part of Daniel, since it only preserves material from Daniel’s prayer in chapter 9. If this is the case — which is likely but impossible to prove — 4QDane would not qualify as a copy of the book of Daniel. (Flint 1997. p. 43)

But wait, it may not be lost, because another scroll, 11Q14 or the Melchizedek scroll, has a line that stops short where we would expect to find it, or at least a few words of it:

This vi[sitation] is the Day of [Salvation] that He has decreed [. . . through Isai]ah the prophet [concerning all the captives,] inasmuch as Scripture sa[ys, “How] beautiful upon the mountains are the fee[t of] the messeng[er] who [an]nounces peace, who brings [good] news, [who announces salvat]ion, who [sa]ys to Zion “Your [di]vine being [reigns”.” (Isa. 52:7).] This scripture’s interpretation: “the mountains” [are] the prophet[s], they w[ho were sent to proclaim God’s truth and to] proph[esy] to all I[srael.] And “the messenger” is the Anointed of the Spir[it,] of whom Dan[iel] spoke; [“After the sixty-two weeks, an Anointed One shall be cut off” (Dan. 9:26) The “messenger who brings] good news, who announ[ces Salvation”] is the one of whom it is wri[tt]en; [“to proclaim the year of the LORD`s favor, the day of the vengeance of our God;] to comfort all who mourn” (Isa. 61:2) (Wise, Abegg and Cook’s translation and commentary, pp. 592-93. The square brackets indicate various types of damage to the scroll. I have greyed these sections.)

Wise, Abegg and Cook’s commentary:

The messenger, also designated “Anointed of the Spirit” (Hebrew messiah), is conceived of as coming with a message from God, a message explicating the course of history (that is, a declaration of when the End shall come) and teaching about God’s truths. (p. 591)

So that anointed one is a messenger, a prophet, delivering a message delivered also by other prophets. The more I investigate the Scrolls and Daniel and Daniel’s sole reference to an anointed one in particular, the less clear it is to me that the community attached to these scrolls had any special interest in the coming of this “anointed” prophetic figure, and far less in expecting him to turn up in their own day, and certainly not with any special eschatological function.

But, but, but…. Don’t we only have a fraction of the original Qumran collection? Could not those writings now lost to us have been infused with speculations about Daniel’s anointed one?

When interest in the book of Daniel is strongest

Well, to help us gain some perspective, let’s look at another text most scholars would date to the first century, one that is pervaded with allusions to the book of Daniel. In fact, in six chapters alone there are 12 quotations of, 22 allusions to, and about 13 signs of the influence of the book of Daniel. Such a single text is sure fire evidence that those it was written for had a very strong interest in Daniel. That text is the Gospel of Mark. (Those allusions, quotations and influences that are found in one chapter of Mark are listed at The little apocalypse of Mark 13 – historical or creative prophecy?.)

Mark is a narrative about a messiah. But despite all of its fascination with the book of Daniel there is not one single hint in it that the “anointed one” of Daniel 9 elicited any interest whatsoever. And in neither the Gospel nor the Qumran writings is there any indication at all of date-setting, calculations to indicate something imminent, etc. Indeed, Jesus in the Gospels insists that the day and hour are unknown. Daniel was an apocalypse anticipating God’s final judgements and rewards but it was not read as a book about messianic hopes according to our earliest “Christian” witnesses.

Recall that the apocalyptic hypothesis (above) has befogged conventional searches for messianic origins in the centuries up to the time of the birth of Christianity. A work can be apocalyptic, it can be inspired by all sorts of eschatological visions and prophecies, but none of that means it has to speak about a messiah. And most apocalyptic works of the era don’t.

Listen to the silence and what do you hear?

Richard Carrier’s appeal to Peter Flint’s chapter (footnote #46) successfully support his claim that the book of Daniel was a very important text and was even considered to be Scripture at Qumran. No surprise that this should be so when we recollect that like the original audience of Daniel’s prophecies, the Qumran community also saw itself driven out and persecuted and surrounded by apostate Jews. But it does not follow that interest in Daniel focused on messianic ideas.

Consider another set of early Christian writings, the New Testament letters attributed to the apostles. A messiah figure dominates those scribblings. There are concerns to establish credentials and beliefs against nonbelievers and mavericks. Yet nowhere is there a hint that anyone thought to consult the calculations from Daniel’s prophecies to prove that Jesus was the real thing. Same with Acts despite all the opportunities to do so in those narrated attempts to prove to unbelieving Jews that Jesus was the messiah despite or rather because of his death?

Carrier emphatically asserts that it was Daniel 9 that was the prophecy Josephus claimed was exciting the Jews to keep up their fight against Rome.

As at Qumran, the key inspiring text was the messianic timetable described in the book of Daniel (in Dan. 9.23-27). By various calculations this could be shown to predict, by the very Word of God, that the messiah would come sometime in the early first century CE. (Carrier 2014, p. 84)

But see my previous post for a more nuanced appreciation of the plausibility of this suggestion. Besides, if the calculations really pointed to the early first century then one wonders how they supposedly inspired some form of maniacal violence forty years, a generation or two, later.

Several examples of these calculations survive in early Christian literature, the clearest appearing in Julius Africanus in the third century.47 The date there calculated is precisely 30 CE; hence it was expected on this calculation (which was simple and straightforward enough that anyone could easily have come up with the same result well before the rise of Christianity) that a messiah would arise and be killed in that year (as we saw Daniel had ‘predicted’ in 9.26: see Element 5), which is an obvious basis for setting the gospel story precisely then . . . , or else a basis for believing that, of all messianic claimants, ‘our’ Jesus Christ was the one for real.

. . . .

47. Julius Africanus, in his lost History of the World, which excerpt survives in the collection of George Syncellus, Excerpts of Chronography 18.2. Other examples of this kind of calculation survive in Tertullian, Answer to the Jews 8, and Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies 1.21.(125-26).

48. Josephus, Jewish War 6.312-16 (Carrier 2014, p. 84)

I do agree with Carrier’s main thesis in Element 5, that some Jews did expect a dying messiah. But Daniel 9 alone does not give rise to that belief. It was primarily about Onias III, don’t forget. This is a discussion for another time, however. Meanwhile anyone interested can review my posts on Boyarin’s and Hengel’s discussions. This series of posts does not deny a wide variety of messianic ideas at the time; it is attempting to point out the lack of evidence we have for messianic fever.

Arguments from silence carry weight when we have very good reasons to expect lots of noise. If, as Carrier suggests, there really was a keen interest among messianic groups of various kinds for dating the arrival of the messiah to around 30 CE from the book of Daniel we would surely have a right to expect evidence to support that scenario. I have pointed above to some of that deafening silence in the Gospels, New Testament epistles and Acts.

So I believe Carrier been courageous in declaring the “clearest” evidence for his argument comes from the third century! (Although see Tertullian, chapter 8, and Clement 1:21).

Cheating at arithmetic

Roger Pearse has made available online excerpts from Syncellus’s Chronography. I have not read those but I have read the relevant sections of the full work and one thing is clear: Syncellus did not start with Daniel’s prophecies and work out a time-table to see where it ended up. He began with the “infallible” rock of Luke 3:1 that declares the whole story began in the fifteenth year of emperor Tiberius. That is, he cheated.

To make Daniel’s 490 years fit, he had to convert lunar years to solar years and even then find ways to fudge the results. It’s a most interesting read, seeing what mental contortions he put himself through to make it all work out. It is very obvious why no-one in the early first century ever calculated Daniel’s prophetic weeks to culminate in 30 CE. What Syncellus, Tertullian and Clement were doing was working backwards, not forwards, to find various ways to make the numbers fit. Had there been straightforward ways of seeing how Daniel’s numbers all pointed to 30 CE among the scribes at that time, and if word had leaked out to the general population to fuel messianic movements, I think we would have a right to expect some evidence of this in our earliest Christian writings, certainly before the late second and third centuries apologists.

Carrier, Richard. 2014. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Flint, Peter W. 1997. “The Daniel Tradition at Qumran”. In Eschatology, Messianism, and the Dead Sea Scrolls, edited by Craig A. Evans and Peter W. Flint, 41-60. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans.

Georgios, Synkellos. 2002. The Chronography of George Synkellos: A Byzantine Chronicle of Universal History from the Creation. Translated by William Adler. New York ; Oxford: OUP.

Kee, Howard C. 1975. “The Function of Scriptural Quotations and Allustions In Mark 11-16.” In Jesus Und Paulus : Festschrift F. Werner Georg Keummel Z. 70. Geburstag, 165-188. Gottingen; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Mack, B. L. 2009. “The Christ and Jewish Wisdom.” In The Messiah: Developments in Earliest Judaism and Christianity, edited by James H. Charlesworth, 192-221. Minneapolis; Fortress Press.

Ulrich, Eugene. 1987. “Daniel Manuscripts from Qumran. Part 1: A Preliminary Edition of 4 QDana.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 268: 17–37. doi:10.2307/1356992.

Wise, Michael, Abegg, Martin and Cook, Edward. 2005. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. San Francisco: Harper.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Far be it from me to question “specialist scholars”, but I’m wondering how they deal with the very nose on the documentary face in the first century CE. (Daniel is too far back to necessitate that it automatically has to reflect and be a part of an early stage of that first century phenomenon; but I think it helped give rise to it.) I’m not going to argue all this in detail but just raise some rather obvious (to me) pointers. The Gospels clearly reflect messianic expectation, and refer to a view of Jesus as “the messiah” (the Petrine Mark’s declaration that Jesus “is the Messiah”) with an obvious understanding of what that meant for both a writer like Mark and his readers, no need for explanation. The only way to get around that is to shove them all into the second century, even after the second Jewish revolt. I’m not the only one who can’t accept that late dating, which within the present debate would smack of circularity.

Then there’s the Similitudes of Enoch, which presents an expected messiah figure (given other titles as well) who reflects much of the supposed messianic expectation traditionally assigned to the times. Once again, late dating of this work, or even the Similitudes portion, is self-serving and hardly to be unquestioned, and many do place it within the first century.

What of the messiah references in the Odes of Solomon? Dating of this work is increasingly pushed back from some very questionable late dating we used to see (Milik’s is all but rejected as untenable now) and it makes better sense to place it in the late first century and even prior to any Gospels. Its “Messiah” is mystically presented, as is so much else in these Odes, but usage of the term suggests it was current in other contexts.

In passing, let’s not ignore Josephus, who while he studiously avoided the term, gives witness in the late first century of a tradition of Jewish prophecy which can only refer to messianic expectation of the traditional sort, even if he reinterprets it for his own purposes.

Then there’s Q. Ah yes, Q. On the conclusion/assumption that Q existed, it had to predate the Gospels, and while it does not use the term “messiah”, its prophesied figure of the Son of Man (no doubt derived in great measure from Daniel) is a messianic idea in all but name. Mark shows that the Son of Man idea and the Messiah idea are being deliberately conjoined, more than suggesting that the latter was a prominent idea that had to be accommodated with the other one; probably they were in some kind of competition in apocalyptic expectation of the day.

Incidentally, I will mention here that I think the biggest flaw (in some respects the only significant one) in Carrier’s book is his ready dismissal of Q, based on very little argument whatsoever other than the simplistic one we’ve heard too often: oh, Q really isn’t necessary since we can just assume the simpler (a la Occam) option that Luke copied Matthew; Goodacre and predecessors present us with a virtually unchallengable no-Q position. Well, I beg to differ. I and many other scholars (more legitimate than myself, of course) have long pointed out the flaws in Goodacre, and Carrier simply does not address them at all. He notably does not address what I consider very powerful observations about the “Q” content in Matthew and Luke which clearly show that pericopes within that content have had previous redaction performed on them, a situation which would be impossible in Goodacre’s position. (Stevan Davies was quite taken aback when I pointed this out, and he said he was going to take up that question with Goodacre!)

By the way, one reason why I cannot argue this or other issues in depth now is that I have gotten rid of virtually all my library of scholarly and source books (this city’s library is now very rich in biblical academic works), due to profound changes in my life in the last couple of years, which will be an indicator of my degree of disengagement with the Jesus mythicism business. Trouble is, every now and then I feel an urge to comment on various debates, relying on my memory (!) and of course my own published books on the subject.

In sum here, while I have the greatest respect for specialist scholars–after all, don’t mythicist scholars fall under that umbrella?–sometimes specialty work may lead one to ignore or overlook things that others find obvious or at least needing addressing. Analyses such as the state of a set of documents like the DSS may be fine, but they may not present the whole or even the sole or predominant picture. (And that’s true of other issues sometimes discussed here on Vridar.)

My reference to “specialist scholars” was not an appeal to authority but a rejoinder to Richard Carrier’s own claim, referenced in the first post, that it is “scholars specializing in messianism” who support his and the traditional wisdom. They don’t. I think it is telling that Carrier relies heavily on one such as Craig Evans.

(Added later: I have since checked and found Carrier actually referred to “experts in ancient messianism” (p. 67))

I will answer in more detail later. I thought I had addressed some of the specifics you raise in previous posts but will do so again and more thoroughly. But do keep in mind

1. that I am addressing the period at the time of Christ (presumed) and not very different Judea of the war years (although as I have previously shown messianism then is also in dispute notwithstanding a face-value and somewhat tendentious reading of Josephus)

2. that there was a wide variety of messianic views through the Second Temple era. That goes without saying, and in fact is a contributory support to the thesis presented in these posts. What is disputed is the scenario of the popular (and even scribal) movements eagerly anticipating a messiah to appear imminently.

Yes, Paul’s whole focus is on a Messiah. But I do not see evidence for the “messianic myth” of imminent messianic expectations in his writings. Apocalypticism, yes. But not the scenario Carrier is disputing.

I will address again when I have more opportunity, and in more depth, your points over specific Second Temple texts. And no, I do not resort to late dating. Nor do I rely on a no-Q model.

Hi Earl!

I was wondering if I could pick your brain about the following passage in Mark:

…4Then Jesus told them, “A prophet is without honor only in his hometown, among his relatives, and in his own household.” 5So He could not perform any miracles there, except to lay His hands on a few of the sick and heal them (Mark 6:5).

Earl, if Mark has Jesus identify himself here as a fallible human prophet who can’t perform miracles in his home town, and Jesus in fact cannot perform miracles in his home town, wouldn’t it make sense to say Mark didn’t view Jesus as a “dying/rising God,” but rather as a “fallible human prophet?” If Jesus was a “god,” shouldn’t he be able to perform miracles in his home town? Doesn’t this piece of recalcitrant evidence present a more original version of what Mark thought about Jesus, and cancel out the legendary embellishment as being representative as a later addition?

Do you think Jesus as a “dying/rising God” is the most “original” portrait of Mark’s presentation of Jesus, or is it Mark’s presentation of Jesus as a “fallible human prophet.”

John

I don’t follow you, Earl. The arguments are based squarely on the first century CE documents. What is it about the argument that appears to defy the first century CE documents?

That’s the very point this post addressed. Presumably you found the argument lacking. I would appreciate a critical engagement with the argument made in that case.

Yes, indeed, and I have said as much in this series of posts. I don’t understand why you think this poses a problem for the argument made here.

The argument in these posts has not attempted to “get around that” but finds no problem with that. No unconventional late dates have been proposed for anything.

Yes indeed we have the Similitudes of Enoch but I don’t understand why you seem to think I am dating it late. I don’t. First century is just fine with me.

But we need to be clear about what we mean by “expected messiah”. Certainly the Similitudes associate the Anointed One with end-time judgment, and I have already stressed that such an association was an exception in the literature of the day (the day = first century CE), not the rule. Enoch does not speak of a messiah coming to rule on earth and there is no evidence that the figure was expected “very soon” from any early first century perspective.

You say the work “reflects much of the supposed messianic expectation traditionally assigned to the time” but it is that supposition that we are arguing lacks supporting evidence. Your reasoning here appears to be circular. Does not the traditional supposition involve a messiah figure coming to rescue the saints or Israel from persecution and/or foreign rulers. That’s not the Enochian figure.

What is it about the Odes’ references to a messiah that speaks to a “messianic expectation”? Once again, you seem to be assuming a context and reference for which we have no evidence.

I invite you to read the previous post in this series where I addressed that argument. Or if you have done so, can you engage with what you found amiss there.

This ties in with the various points made earlier about the Christian sources but I fail to see how your remarks engage with the arguments.

I agree, and have expressed that same point both here and elsewhere. I am disappointed sometimes over the casual dismissal of Q one encounters. The question deserves and requires an in depth study of the details of the arguments on both sides. Too many do express an unsatisfactory almost casual dismissal of the alternative. But I think the fault often lies on both sides: some of those on the Q side do not indicate any serious attempt to understand the more serious arguments for Luke’s use of Matthew. Both sides too often take up adversarial positions.

I have seen arguments against Goodacre’s views but not the establishment of definitive flaws. I understood there is still room for debate. You disagree, it seems.

Was that on Crosstalk? I will try to track that down.

I would appreciate you being open and telling me exactly what other issues you mean. If you are speaking about issues relating to terrorism, I recall you once saying you thought Vridar to be an appropriate place to discuss such things.* But you have not participated in any engagement with views you find distasteful. If you believe my understanding is limited I would expect you to explain to me where I am lacking and to engage in serious discussion so neither of us is limited to but a partial picture.

* You commented

Great…many commentators too eagerly equate apocalypticism with messianism.