Here I have copied the previous post without the table format (which can only be fully seen on certain browser settings).

Ever since my earlier post Why the Anonymous Gospels? Failure of Scholarship in Pitre’s The Case for Jesus I have intended to address Brant Pitre’s grossly misleading suggestion that all our earliest canonical gospel manuscripts come with the titles we know them by today — Gospel According to Matthew or simply According to Matthew…. etc. and that the argument that the gospels were anonymous until the end of the second century is baseless. Time and other things got in the way but then I read Bart Ehrman presenting the argument for the gospels being anonymous until towards 200 CE and thought that should save me the trouble. So below I have posted side by side Pitre’s and Ehrman’s respective arguments. (In places Ehrman appears to claim the argument as his own but in fact one finds it in works of earlier scholars, too.) I have also included material that is from sources other than Ehrman. I don’t claim to have covered all possible responses to Pitre’s assertions and suggestions in this post, but hopefully there is enough to make a sound assessment of his claims. Feel free to add other points.

—o0o—

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre

[I]n the last century or so, a new theory came onto the scene. According to this theory, the traditional Christian ideas about who wrote the Gospels are not in fact true. Instead, scholars began to propose that the four Gospels were originally anonymous.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 13). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

It is especially emphasized by those who wish to cast doubts on the historical reliability of the portrait of Jesus in the four Gospels. The only problem is that the theory is almost completely baseless.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 16). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

–o–

Jesus before the gospels / Bart Ehrman

In short, the Gospel writers are all anonymous. None of them gives us any concrete information about their identity. So when did they come to be known as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John? I will argue they were not called by those names until near the end of the second Christian century, a hundred years or so after these books had been in circulation.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 93). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

The first thing to emphasize about Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John is that all four are completely anonymous. The authors never indicate who they are. They never name themselves. They never give any direct, personal identification of any kind whatsoever.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 90). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

—o0o—

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre

The first and perhaps biggest problem for the theory of the anonymous Gospels is this: no anonymous copies of Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John have ever been found. They do not exist. As far as we know, they never have.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 16). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

the ancient manuscripts are unanimous in attributing these books to the apostles and their companions.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 16). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

–o–

The Anonymity of the New Testament History Books / Armin Baum

The anonymity of the New Testament historical books should not be regarded as peculiar to early Christian literature nor should it be interpreted in the context of Greco-Roman historiography. The striking fact that the New Testament Gospels and Acts do not mention their authors’ names has its literary counterpart in the anonymity of the Old Testament history books, whereas Old Testament anonymity itself is rooted in the literary conventions of the Ancient Near East.

The Anonymity of the New Testament History Books: A Stylistic Device in the Context of Greco-Roman and Ancient near Eastern Literature; Author(s): Armin D. Baum; Source: Novum Testamentum, Vol. 50, Fasc. 2 (2008), pp. 120-142; Published by: Brill; Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25442594

—o0o—

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre

The first and perhaps biggest problem for the theory of the anonymous Gospels is this: no anonymous copies of Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John have ever been found. They do not exist. As far as we know, they never have.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 16). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

the ancient manuscripts are unanimous in attributing these books to the apostles and their companions.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 16). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

–o–

Jesus before the gospels / Bart Ehrman

It needs to be pointed out that we don’t start getting manuscripts with Gospel titles in them until about the year 200 CE. The few fragments of the Gospels that survive from before that time never include the beginning of the texts (e.g., the first verses of Matthew or Mark, etc.), so we don’t know if those earlier fragments had titles on their Gospels. More important, if these Gospels had gone by their now-familiar names from the outset, or even from the beginning of the second century, it is very hard indeed to explain why the church fathers who quoted them never called them by name. They quoted them as if they had no specific author attached to them.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 105). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

—o0o—

No Anonymous Copies Exist?

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre

First, there is a striking absence of any anonymous Gospel manuscripts. That is because they don’t exist. Not even one.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 17). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

When it comes to the titles of the Gospels, not only the earliest and best manuscripts, but all of the ancient manuscripts— without exception, in every language— attribute the four Gospels to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 17). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

there is “absolute uniformity” in the authors to whom each of the books is attributed.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 17). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

In fact, it is precisely the familiar names of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John that are found in every single manuscript we possess! According to the basic rules of textual criticism, then, if anything is original in the titles, it is the names of the authors. 18 They are at least as original as any other part of the Gospels for which we have unanimous manuscript evidence.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 17). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

In short, the earliest and best copies of the four Gospels are unanimously attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. There is absolutely no manuscript evidence— and thus no actual historical evidence— to support the claim that “originally” the Gospels had no titles.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 18). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

.

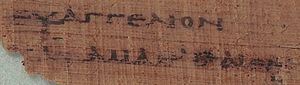

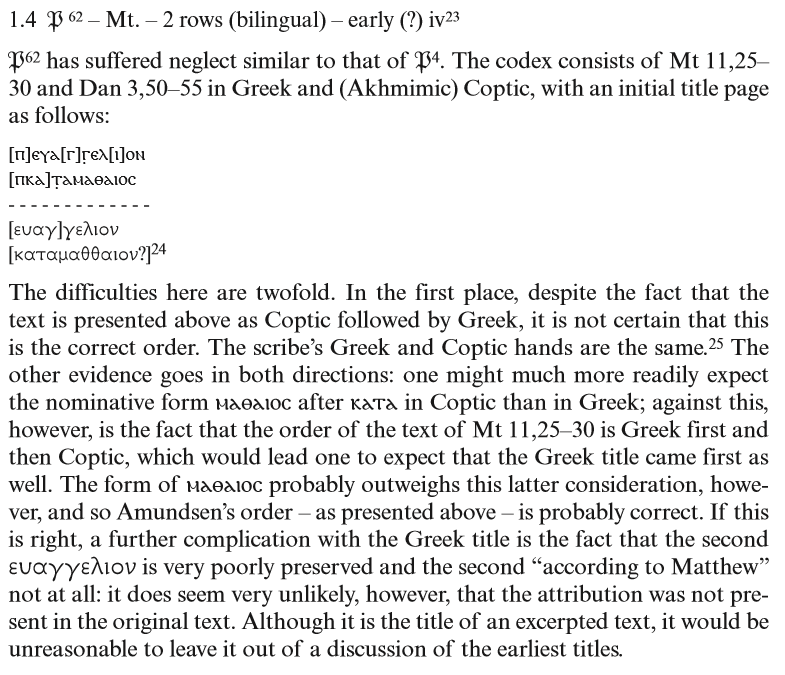

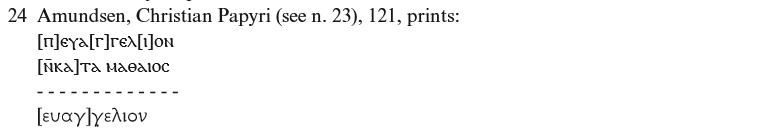

What Papyrus 4 and Papyrus 62 Really Look Like

Pitre’s table in the context of his text leads readers to believe that we have Gospels of Matthew with headed by that title as early as the second century and well before 200 CE. Papyrus 4 in the literature (as reflected in the Wikipedia articles from which the images and captions below are taken) is in fact dated as likely from the third century. It contains a flyleaf of the title of Matthew’s gospel without any gospel text.

Pitre’s table in the left column leads readers to believe that we have Gospels of Matthew with headed by that title as early as the second century. Papyrus 4 in the literature (as reflected in the Wikipedia articles from which the images and captions below are taken) is in fact dated as likely from the third century. It contains a flyleaf of the title of Matthew’s gospel without any gospel text.

Papyrus 62 in the literature is generally dated to the fourth century.

Extract from Simon Gathercole’s ‘The Titles of the Gospels in the Earliest New Testament Manuscripts’, Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 104.1 (2013), pp. 33-76.

—o0o—

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre

and this is important— notice also that the titles are present in the most ancient copies of each Gospel we possess, including the earliest fragments,

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (pp. 17-18). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

For example, the earliest Greek manuscript of the Gospel of Matthew contains the title “The Gospel according to Matthew” (Greek euangelion kata Matthaion) (Papyrus 4).

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 18). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 18). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

The second major problem with the theory of the anonymous Gospels is the utter implausibility that a book circulating around the Roman Empire without a title for almost a hundred years could somehow at some point be attributed to exactly the same author by scribes throughout the world and yet leave no trace of disagreement in any manuscripts. 20 And, by the way, this is supposed to have happened not just once, but with each one of the four Gospels.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (pp. 18-19). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

–o–

Jesus before the gospels / Bart Ehrman

here is one other reason for thinking that the Gospels did not originally circulate with the titles “According to Matthew,” “According to Mark,” and so on. Anyone who calls a book the Gospel “According to [someone],” is doing so to differentiate it from other Gospels. This one is Matthew’s version. And that one is John’s, etc. It is only when you have a collection of the Gospels that you need to begin to differentiate among them to indicate which is which. That’s what these titles do. Obviously the authors themselves did not give them these titles: no one titles their book “According to . . . Me.” Whoever did give the Gospels these titles was someone who had a collection of them and wanted to identify which was which.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (pp. 105-106). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

—o0o—

The Anonymous Scenario Is Incredible?

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre

Now, we know from the Gospel of Luke that “many” accounts of the life of Jesus were already in circulation by the time he wrote (see Luke 1: 1-4). So to suggest that no titles whatsoever were added to the Gospels until the late second century AD completely fails to take into account the fact that multiple Gospels were already circulating before Luke ever set pen to papyrus, and that there would be a practical need to identify these books.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 21). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

–o–

Jesus before the gospels / Bart Ehrman

In the various Apostolic Fathers there are numerous quotations of the Gospels of the New Testament, especially Matthew and Luke. What is striking about these quotations is that in none of them does any of these authors ascribe a name to the books they are quoting. Isn’t that a bit odd? If they wanted to assign “authority” to the quotation, why wouldn’t they indicate who wrote it?

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 93). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

This is true of all our references to the Gospels prior to the end of the second century. The Gospels are known, read, and cited as authorities. But they are never named or associated with an eyewitness to the life of Jesus.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 95). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

In these books Justin quotes Matthew, Mark, and Luke on numerous occasions, and possibly the Gospel of John twice, but he never calls them by name. Instead he calls them “memoirs of the apostles.” It is not clear what that is supposed to mean— whether they are books written by apostles, or books that contain the memoirs the apostles had passed along to others, or something else. Part of the confusion is that when Justin quotes the Synoptic Gospels, he blends passages from one book with another, so that it is very hard to parse out which Gospel he has in mind. So jumbled are his quotations that many scholars think he is not actually quoting our Gospels at all, but a kind of “harmony” of the Gospels that took the three Synoptics and created one mega-Gospel out of them, possibly with one or more other Gospels. 33 If that’s the case, it would suggest that even in Rome, the most influential church already by this time, the Gospels— as a collection of four and only four books— had not reached any kind of authoritative status.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (pp. 102-103). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

It is not until nearer the end of the second century that anyone of record quotes our four Gospels and calls them Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. That first happens in the writings of Irenaeus, whose five-volume work Against the Heresies, written in about 185 CE,

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 103). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

It is striking that at about the same time another source also indicates that there are four authoritative Gospels. This is the famous Muratorian Fragment,

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 104). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

This is remarkable. Before this time and place, nowhere are the Gospels said to be four in number and nowhere are they named as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 105). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

—o0o—

Why Choose Mark and Luke as Authors?

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre

The third major problem with the theory of the anonymous Gospels has to do with the claim that the false attributions were added a century later to give the Gospels “much needed authority.” 26 If this were true, then why are two of the four Gospels attributed to non-eyewitnesses? Why, of all people, would ancient scribes pick Mark and Luke, who (as we will see in chapter 3) never even knew Jesus?

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 22). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

–o–

Jesus before the gospels / Bart Ehrman

That leaves the Gospel of Mark. One can see why the Gospel of Luke would not have been named after one of Jesus’s own disciples. But what about Mark? Here too there was a compelling logic. For one thing, since the days of Papias, it was thought that Peter’s version of Jesus’s life had been written by one of his companions named Mark. Here was a Gospel that needed an author assigned to it. There was every reason in the world to want to assign it to the authority of Peter. Remember, the edition of the four Gospels in which they were first named, following my hypothesis, originated in Rome. Traditionally, the founders of the Roman church were said to be Peter and Paul. The third Gospel is Paul’s version. The second must be Peter’s. Thus it makes sense that the Gospels were assigned to the authority of Peter and Paul, written by their close companions Mark and Luke. These are the Roman Gospels in particular.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 111). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

The main reason there may have been reluctance to assign this book directly to Peter (the “Gospel of Peter”) was because there already was a Gospel of Peter in circulation that was seen by some Christians as heretical

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (pp. 111-112). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

Acts is told in the third person, except in four passages dealing with Paul’s travels, where the author moves into a first-person narrative, indicating what “we” were doing (16: 10– 17; 20: 5– 15; 21: 1– 18; and 27: 1– 28: 16). That was taken to suggest that the author of Acts— and therefore of the third Gospel— must have been a traveling companion of Paul. Moreover, this author’s ultimate concern is with the spread of the Christian message among gentiles. That must mean, it was reasoned, that he too was a gentile. So the only question is whether we know of a gentile traveling companion of Paul. Yes we do: Luke, the “beloved physician” named in Colossians 4: 14. Thus Luke was the author of the third Gospel. 37

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 111). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

—o0o—

Could Peter and John Even Write?

Acts 4: 13 says [Peter and] John [were] literally “unlettered” (Greek, agrammatos)— that is, [they] did not know [their] alphabet.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 93). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

In English, a phrase like “The Gospel of Mark,” has had at least two possible meanings. And one of them is just that we are being presented with a gospel not written by Mark, but one merely say, OWNED by Mark.

Our English preposition “of” has many meanings. And is very ambiguous.

Anyone care to talk about what the original Greek looks like?

Example: “The manuscripts of the Library of Congress are available online.”

it is “kata” — “according to”: http://biblehub.com/greek/2596.htm

euangelion kata Matthaion

Could even that mean not 1) “written by,” but 2) as referred to by? As I recall, there have been scholarly articles that read these titles as not referring to authors, but various schools, headed by figures like Mark. Which in turn were perhaps in possession of still other materials.

So for example, we might refer to “pop culture, according to Adorno, and the Frankfurt school.” Adorno and the Frankfurt School, would be commentators on, but not the author of, pop culture.

As I recall, many attempts were made to suggest this: that the names referred to at most the heads of various regional traditions or schools. And not original authors.

By the way, Pitre publishes often with known, self-confessed Catholic apologists, like Robert Baron and others. However, he says that he is now considering in effect, more liberal positions. On the Le Donne blog, he seems mostly open to many positions, for now. As a theologian from New Orleans or sin city, he has to be somewhat receptive to liberal thinking. As with most of the Le Donne crowd, I see him as a conservative who however, will listen, albeit impatiently, to other positions or schools.

I don’t understand that group of scholars. How can Crossley sit intellectually alongside the likes of Pitre? Crossley has written about religious bias in the strongest terms and it would appear that by being part of that group on the HJ blog he is sleeping with his enemies. I guess he may be seen as a classic case study of the unbeliever who is obliged to think within certain correct parameters simply to attain the professional acceptance needed to survive. He writes of the Chomsky model but from where I stand he fails to see how he himself is part of it. He would deny this, I presume, but if so then he would be still falling in with the Chomsky model of complying with certain minimum of correct thoughts simply in order to be where he is today.

Chomsky sounds about right.

I think that whole group is conflicted, torn. They’re coming 1) from a believing background. But they 2) are trained in a somewhat more critical academic approach. Which they are pursuing, but somewhat uncomfortably.

They are mostly torn … and don’t quite have the consistently critical mindset of say, atheists.

Like nearly all employed scholars today, they will question every individual element of Christianity … but cannot finally give it all up, publicly. In part because of massive social disapproval.

Crossley sees it. But doesn’t quite have the courage of his convictions, consistently.

Partly, they’re young?

Le Donne sees it, too.

Generally they’re resistant. But they reluctantly accept a polite, intelligent argument.

I’m hoping they can be converted one day to a more critical perspective.

Yes, there are a range of possible options for what lies behind “according to/kata”. But one constant remains: that all four gospels bear the same form of title. Ehrman’s explanation (though he is hardly the originator of the hypothesis) makes the most sense to me.

Ehrman sounds OK here. But I’m currently following scholarship that posits different regional traditions. possibly the names, name prominent persons in regional traditions. The name Mark is extremely Roman. Luke is Greek. Don’t know about Mat and John. John was thought to be Cypriot?

“Matthew” as it turns out, was originally Hebrew.

So it looks also like we’ve got four regions – and probably four different churches. The 1)Roman Church; the 2)Greek Orthodox. The 3)Jerusalem or Judean Christians’ church.

John I’m still trying to figure out. He’s an odd one. Maybe he stands for 4)hermits. And their odd ascetic, farflung redoubts, caves. And their prophetic apocalyptic.

People who live in the wilderness, often do that because they hate the often hypocritical and apparently corrupt social “world.” And they are always predicting its apocalyptic end, due to internal corruption.

John was said to be a sort of hermit in, as it happened, the Island of Cyprus.

‘“Matthew” as it turns out, was originally Hebrew.’

Well, there was a rumor among our proto-orthodox authors that Matthew had written the earliest gospel in “Hebrew” (presumably Aramaic), which was used by Nasoreans/Essenes, and which the canonical GMatthew was spuriously identified with.

I think that when, toward the end of the second century, Irenaus decided that his “Universal” Church should use precisely *four* of the many gospels then floating around to reflect the “Four Corners of the Earth” and the “Four Winds”, he chose ones not just generally amenable to his own theology, but ones which he thought represented the geographic range of earlier Christianity: GMatthew from Judea, GMark from Egypt, GLuke from Syria, and GJohn from Asia (a Catholic revision of some lost Gnostic work with a whole nother, even more obscure history – but to judge from existing fragmentary documents, it was the most popular gospel of the time; so there it is).

Matthew copies at length Mark’s Greek text — indicating Matthew itself was originally composed in Greek. Papias asserts Matthew was originally composed in Hebrew (Aramaic?) but Papias also claims Matthew is a “sayings gospel” (like Q and Thomas). Our Matthew is clearly not a “sayings gospel” so we have to conclude whatever Papias is talking about according to our Eusebius quotation it is not the Gospel of Matthew that we know.

Ehrman presents the above argument without any citations but he appears to acknowledge he is not the originator of it when he says “virtually every critical scholar on the planet” disputes Papias’s claim about the Hebrew text of Matthew. I first learned of the arguments from reading Earl Doherty’s works.

Possibly though we’ve just proposed the resolution. There was an earlier Hebrew Matthew. The one we have today was a later Greek rewrite. Incorporating many Greek, Markan elements.

In general, regarding the gospels, I firmly believe that our present forms of them were not the original documents. What we have today is later Roman, Greek rewrites. Even especially, Mark.

The name Matthew is originally Hebrew. (So is John, by the way.)

I know of no reason to think our Gospel according to Matthew was originally associated with the name Matthew.

As for a Hebrew original we need to look into studies of the nature of the Greek text and whether there is evidence of it being based on a Hebrew original. I did that many years ago and don’t recall the details but the conclusion was negative.

Papias suggested it? And his assertion that it was a sayings gospel would confirm my model of an earlier document. Probably Hebrew. Later all but totally effaced, but not completely, by Roman Greek editorialization and interpolation. Probably by the early Roman and Greek churches.

In this model, the probably Roman Markan material would have been imposed over, or added alongside, earlier Hebrew.

Corresponding to, as part of, the increasing takeover of Judah and Christianity by Greek and Roman forces, churches, congregations, armies.

Papias can be discarded as evidence for anything related to our canonical gospels — and normally is except by those still bound within the model attributing some veracity to the traditions associated with those gospels.

Earl Doherty, Jesus Neither God Nor Man, pp. 467-468

Ehrman has also demolished attempts to use Papias as having any relevance to the gospels we know. Just to quote one section of lengthy arguments:

And as I’ve quoted several times before, such warnings against using Papias as evidence for anything are a century old:

A case can be made that anonymity actually adds to the mystique and importance, and ultimate acceptance of a book. One of the arguments used against heretics was that the author of their divine writings was actually known. There are multiple examples of anonymity in religious literature of the period. There is no reason to doubt that the gospels and Acts were not of the same genre. The eventual attribution of authorship happened long after the books were accepted. I have to agree with Ehrman on this point.

Yes. Particularly when he notes that beyond the title, furthermore, the interior text itself dies not suggest a singular reliable author. The extremely equivocal ending of John for example, includes an editorial “we” as commentator on any earlier apostolic source.

This is an interesting idea and one I have sometimes thought about, especially in the context of the anonymous historical books of the Jewish Scriptures. But then there are two factors that lead me to reconsider: an article I cite in the above post points out that anonymity was a feature of ancient Near Eastern historical writings; and the lack of authority that is evident in the gospels in their earlier years. On the former, I don’t know if the anonymity was a device used to express divine/inspired authority (as distinct from a person who writes from the context of a narrow/filtered perspective) or if there are other reasons to account for it. On the latter, it is evident that the first gospel (known to us as Mark) was not considered authoritative because Matthew and Luke, and I also think “John”, felt quite free to change it, to engage in dialogue with it. And ditto if Luke used Matthew, and if Luke also used John or if John used any of the others. We see the same in the OT writings where, for example, it is evident that Isaiah and Micah are in dialogue with each other, each expressing their own variant of common themes.

So it does appear that anonymity was not interpreted by contemporaries as an “authoritative” or “mysterious” device.

Even though the gospels appear to convey history, there is no reason to trust them. If you would like to read the short story I published about the possibility that the stories of Jesus’ divinity and miracles were LIES, it is published here:

http://www.caseagainstfaith.com/the-eternal-return.html

For an overview of the most recent arguments I have on the topic of “Jesus’ divinity and miracles as NOBLE LIES,” see the five or six posted comments I have on this blog page:

http://vridar.org/2015/09/21/comments-open/#comment-73290

My name is John MacDonald

Thanks John. I enjoy your regular posts. And I sometimes see religion as simply a lie as well. Though I usually avoid the term for various reasons.

May look you up sometime later.

You should check out the short story. It’s really controversial lol.

Hi,

Great post as usual. A while ago you posted a link to bible-related forum, but I forgot what post it was in or the name of the forum. I wonder if you could provide a link to the forum? The name of the forum was written using Greek letters.

Cheers,

Tim.

It was probably the Biblical Criticism & History Forum

Ehrman in his new book says the crucifixion by the known historical figure Pilate is historical bedrock (Jesus Before The Gospels, 149). I don’t know why he thinks this, because the mention of the Census of the known historical figure Quirinius is also indicated in the gospels as connecting to Jesus, but there is no reason to think this event has any real connection to Jesus. There seems to be a bias among the academy that if a real historical personage is mentioned in the gospels in connection to Jesus (like Pilate or John The Baptist), the rule of thumb is to accept the relationship as historical unless there is direct evidence suggesting otherwise (the Census of Quirinius). This is a paralogism of course.

The Census of Quirinius was supposedly a census of Judaea taken by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, Roman governor of Syria, upon the imposition of direct Roman rule in 6 CE. According to the Gospel of Luke, Jesus was born at the time of the census and during the reign of Herod the Great, but Herod died in 4 BCE; no satisfactory explanation has been put forward which could resolve the contradiction.

The point is, there is no more reason to suppose Pilate is connected to Jesus, than to suppose the Census by Quirinius was. The most parsimonious explanation seems to be that the gospel writers were constructing historical fiction by including famous personages in the tale, much like an encounter with Abe Lincoln might appear in an historical fiction novel about The Civil War.

There is indeed 1) no historical reason for supporting specifically the crucifixion as bedrock.

Some might 2) support it thanks to the Criterion of Embarrassment. Which says that the whole idea of our savior dying is so illogical, no one would make it up. But this and other Criteria were recently debunked.

So finally, the 3) real reason Ehrman takes the crucifixion as bedrock, is that recent evangelical dogma demanded it.

Over the last ten or twenty years or more, a curious new doctrine has become enormously popular in evangelical circles. It was based allegedly on a line from Paul. That without the crucifixion, the whole of Christianity collapses. The notion of Jesus dying for our sins, for example, presumably, required that death.

And so? In recent decades, the crucifixion has been taken by many churches for the most important idea of all. And? It became in effect, the main shibboleth, the main litmus test, to use to see if someone is Christian. And to see if you yourself are Christian. Do you believe that the crucifixion was real? You are allowed to disbelieve everything else. But if you believe this fig leaf, then you can rest easy that in spite if all your doubts, you have not left Christianity, to become an unbeliever.

It’s just a fig leaf. But it’s become enormously popular. And for that matter, it allowed millions to question almost everything in Christianity, without troubling their conscience.

So the real reason Ehrman embraces the crucifixion as more real than anything, is indeed not based on history. But on a fairly new evangelical, theological doctrine. One that in some ways is conservative. But in other ways, rather liberal. In either case though, it is based on a perceived theological need. Not on History.

Ehrman is three fourths, or even nine tenths of the way, to being a full critical thinker. But after all, it’s hard to shake off 40 years of church and Sunday School and Moody Bible College, and seminary. And then too, Ehrman probably deliberately makes some concessions to the huge audience of people. Who likewise, want to make the move to full rational objectivity. But who are not quite ready to cast off the last rope tying them to shore.

Curious. The entire above post has one letter of the alphabet taken out of everything. The first person letter: I, or “i.”

VIRUS ALERT? JUST MY COMPUTER OR YOURS?

THE LOWER CASE LETTER “I” IS BEING TAKEN OUT OF COMMENTS

I’m seeing this as well, on comments from posts from years ago. Must be a very weird bug somewhere.

All is well. No malware here, just a weird bug, as James noted.

Good point about the crucifixion being a theological (as distinct from a historical) fact. I particularly like it because it supports what I have been saying for some years now — at least since this 2007 post: (revised) Spong on Jesus’ historicity: John the Baptist and the Crucifixion 😉 Glad to see it resurface here.

So I see I slept through some drama last night. Glad all is fixed. Thanks to everyone involved.

I’m sure we’ve all gone through some evolutionary changes over the years. But I’ve always been intrigued by that terminology. And it seems very appropriate, and easy to prove. Considering that many advocates of a strong historicity, have ThD – or Theology Doctor – after their names.

And? By far the vast majority of religion writers supporting an ” historical” Jesus, actually know next to nothing about the general practices of actual historians. (At best they know only highly selected and misrepresentative parts.)

Paul says clearly that the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection ALL served a theological purpose for the first Christians. He writes “Christ died for our sins ACCORDING TO THE SCRIPTURES, and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day ACCORDING TO THE SCRIPTURES (1 Cor 15: 3-4).” Standard interpretation protocol says we must set them aside in terms of historicity, because the original Christians had reason to invent them. As Ehrman says about biblical hermeneutics, we assert that events are likely to belong to the historical Jesus when these events “do not appear to be remembered in any prejudicial way – for example, because they represent episodes of Jesus’ life that Christians particularly would have wanted to say happened for their own, later, benefit (Jesus Before The Gospels, 148).” Where Ehrman’s philosophy of biblical hermeneutics falls apart is that he thinks that an event can be considered to be historical because it is mundane, even though this analysis would force us to include the mundane events in the apocryphal books about Jesus into the historical Jesus’ biography.

Then too, the fact that a piece of writing contains mundane things, does not prove that it was was true. Historical novels often put fictional characters, into real historical settings.

And for that matter? Even mundane statements themselves can be false. Liars often lie about mundane things. I might say “the cat is at grandma’s house,” when I know perfectly well the cat is squished in the road, two blocks down the street.

Then too finally, people often are simply honestly wrong about mundane matters. They believe and say the tree is an oak, when it is really a pine tree.

Mere mundanity therefore, is no guarantee of the truthfulness or accuracy of any given statement.

Ehrman therefore, like other supporters of historical Jesus, seems incredibly naive here.

If it sounds plausible or everyday, then it must be true?

The methodological assumptions of Historical Jesus theories are clearly absurd cases of faith-based wishful thinking..

Nobody really believes such things in real life. Only in historical Jesus studies.

I really enjoy posting here at Vridar. Neil has a wealth of knowledge! I learn a lot.

Complimenting Neil, I sometimes try to fill in with obvious basics, that evangelists often seem to miss.

I’m guessing most readers here can skip ahead of some of this. But I’m throwing in a few simple lessons in, for instance, logic, now and then. Just in case we have an evangelical reader or two, who wants a little background.

No point in preaching just to the choir.

Regular complementary comments end up dominating the comments. Remember our comments moderation policy and the maxim that less is more. We once had a Brettongarcia here who outwore his welcome and overwhelming presence with volumes of “complementary comments” that really belonged on a separate blog of his own.

there is a problem with these responses. there are missing letters in every word

ANYONE KNOW HOW TO CONTACT NEIL OR ADMINISTRATOR DIRECTLY, AND SOON?

PRESUMABLY NEIL GETS NOTIFICATIONS OF ALL THESE COMMENTS, BUT IT’S LATE AT NIGHT IN AUSTRALIA.

IF HE DOES SEE THIS, THE RESOLUTION IS HERE: https://wordpress.org/support/topIc/jetpack-393-shortcode-embeds-cause-mIssIng-letters

(CHANGE UPPER CASE ‘I’ TO LOWER CASE ‘I’ IN ABOVE URL).

I’m looking into it right now. –Tim

Thanks for the tip, James. And now it appears the latest version of Jetpack I installed fixed the problem for good.

Thanks, Tim, all working here now.

Hope I didn’t push a few wrong buttons inputting a few comments ago. Might have though.

8:08 UTC comment?

Looks fine. I’m so relieved I didn’t break it!