| By the roots of my hair some god got hold of me. I sizzled in his blue volts like a desert prophet. — Sylvia Plath, quoted by Charles Camerson in So: How Does It Feel at World’s End?, an exploration into the eschatological lure of ISIS. |

Charles Cameron is blogging about a book of his that is hopefully will be published soon: Jihad and the Passion of ISIS: Making Sense of Religious Violence. The first of these blog posts is On the horrors of apocalyptic warfare, 1: its sheer intensity.

Cameron builds on a number of works that I have posted about here on Vridar, so I am looking forward to his own contribution. He writes:

Vridar posts —

- Stern and Berger, Another study of ISIS

- Jason Burke, Origins of Islamic Militancy & Why attack West?

- Weiss & Hassan, ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror

- Will McCants, In Religious Thrill; Revolutionary Terror; Convinced to Kill; & Seeking Status and Adventure.

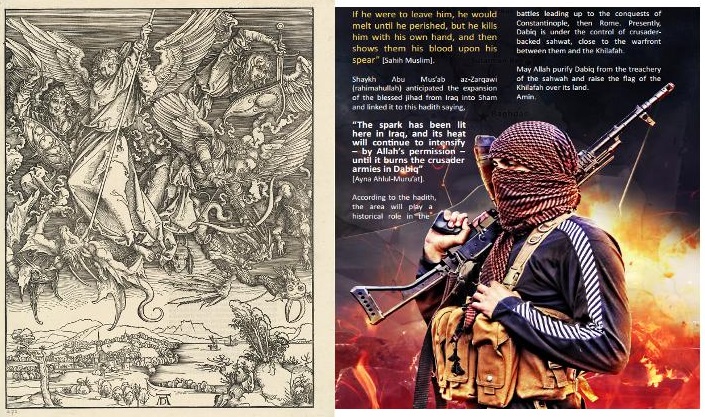

We now have, I believe, a strong understanding of the Islamic State and its origins in such books as Stern & Berger, ISIS: The State of Terror, Jason Burke, The New Threat, Joby Warrick, Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS, and Weiss & Hassan, ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror. Delving directly into the key issue that interests me personally, the eschatology of the Islamic State, we have Will McCants‘ definitive The ISIS Apocalypse. My own contribution will hopefully supplement these riches, and McCants’ book in particular, with a comparative overview of religious violence across continents and centuries, and a particular focus on the passions engendered in both religious and secular movements when the definitive transformation of the world seems close at hand.

What follows is the first section of a four-part exploration of the horrors of apocalyptic war.

Cameron draws upon a dramatically colourful Winston Churchill account to convey the power of the Mahdi on the imaginations of followers in his day.

In his second post On the horrors of apocalyptic warfare, 2: to spark a messianic fire he encapsulates the sense of apoclyptic fervour in a passage from another book on my “to-read list”, Richard Landes’ Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience:

For people who have entered apocalyptic time, everything quickens, enlivens, coheres. They become semiotically aroused — everything has meaning, patterns. The smallest incident can have immense importance and open the way to an entirely new vision of the world, one in which forces unseen by other mortals operate. If the warrior lives with death at his shoulder, then apocalyptic warriors live with cosmic salvation before them, just beyond their grasp.

I’m looking forward to the remainder of Charles Cameron’s series.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Who is apocalyptic and who isn’t? The Germans in ww2 were. The US? Britain? Russia? Maoists?

Interesting question. I don’t know yet much about Charles Cameron’s views but he has written:

He also writes:

I draws distinctions I am not clear about, and blurs two concepts in a way I am also not sure about. Fundamentalists and Apocalypticists; believers in the return/appearance of Christ/Mahdi yet there is something “suggestive” here nonetheless . . . .

Still to find out more. (I recall what it was like to belong to an apocalyptic sect for a while and recall well some of the feelings he describes. — Hence, perhaps, some of my own questions about some of his thoughts.)

But I decided I need to read at the very least one more book before getting into this topic in any sort of depth, and it’s waiting in my Kindle queue — Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience by Richard Landes. . . .

Which eventually brings me to the relevance of this comment to yours! 😉 Landes has a chapter “Genocidal Millennialism: Nazi Paranoia”.

The apocalypse unfortunately, is read as involving massive physical destruction and mega deaths.

To disarm that, and to try to prevent this from becoming a self fulfilling prophesy, I frame the apocalypse as a metaphor. For the day we grow up – and see that religion, its heaven, was a myth.

In that moment, as foretold, the old idea of earth and heaven, collapses. But there’s no need for physical destruction. It’s just a metaphor for the destruction of childhood, religious delusions.