| Scot McKnight is an American New Testament scholar, historian of early Christianity, theologian, speaker, author and blogger who has written widely on the historical Jesus, early Christianity, the emerging church and missional church movements, spiritual formation and Christian living. He is currently Professor of New Testament at Northern Baptist Theological Seminary in Lombard, IL. McKnight is an ordained Anglican with anabaptist leanings, and has also written frequently on issues in modern anabaptism. — Wikipedia (4th Oct 2015) |

I cited Scot McKnight in my first serious attempt to point out the differences in the ways biblical scholars approach their study of Jesus and Christian origins from the ways other historians handled sources and investigated other historical persons and events. In Jesus and His Death McKnight quite rightly notes the general ignorance among his theologian/biblical studies peers of the methods followed by other historians and their debates over the very nature of their craft. He notes that the reliance upon criteria of authenticity (“criteriology”) is both unique to historical Jesus studies and fallacious. In another early post I quoted McKnight’s view that historical Jesus scholars are in fact fooling themselves when they claim their reconstructions of Jesus are derived solely from the evidence:

I cited Scot McKnight in my first serious attempt to point out the differences in the ways biblical scholars approach their study of Jesus and Christian origins from the ways other historians handled sources and investigated other historical persons and events. In Jesus and His Death McKnight quite rightly notes the general ignorance among his theologian/biblical studies peers of the methods followed by other historians and their debates over the very nature of their craft. He notes that the reliance upon criteria of authenticity (“criteriology”) is both unique to historical Jesus studies and fallacious. In another early post I quoted McKnight’s view that historical Jesus scholars are in fact fooling themselves when they claim their reconstructions of Jesus are derived solely from the evidence:

While each may make the claim that they are simply after the facts and simply trying to figure out what Jesus was really like—and while most don’t quite say this, most do think this is what they are doing— nearly every one of them presents what they would like the church, or others with faith, to think about Jesus. Clear examples of this can be found in the studies of Marcus Borg, N.T. Wright, E.P. Sanders, and B.D. Chilton—in fact, we would not be far short of the mark if we claimed that this pertains to each scholar—always and forever. And each claims that his or her presentation of Jesus is rooted in the evidence, and only in the evidence. (Jesus and His Death, p. 36)

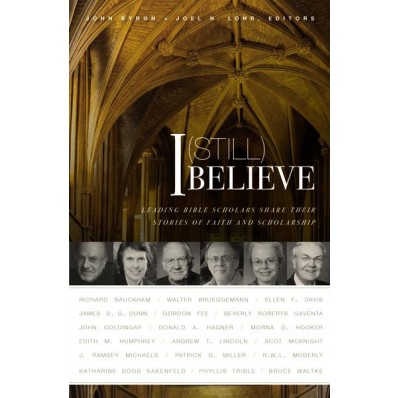

McKnight has elaborated on some of his views about historical Jesus scholarship and the nature of biblical source material in a new publication, I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship.

The Bible is God’s true and living word

McKnight does not hide his view that his historical studies are investigations into “God’s true and living word”. Don’t call him an inerrantist, though. Rather, each book in the Bible adds to the previous one, “sometimes agreeing, sometimes even disagreeing, but often expanding and adjusting and renewing — the previous texts. God’s inspiration then is at work in a history and a community as expressed by an author for a given moment.”

It was not until many years later that I read Michael Fishbane’s Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel when he gave me the best words for what is happening in the Bible and not least in the Synoptics. There is an inner dialogue at work and once one begins to see the dialogue one sees the Bible for what it really is. It is not one self-contained text added to the previous but one text interacting with — sometimes agreeing, sometimes even disagreeing, but often expanding and adjusting and renewing — the previous texts. God’s inspiration then is at work in a history and a community as expressed by an author for a given moment. This experience of underlining the Synoptics one word and one line after another led me to think that words like “inerrancy” are inadequate descriptions of what is going in the Bible. I have for a long time preferred the word “true” or “truth.” The Bible is God’s true and living Word is far more in line with the realities of the Bible itself than the political terms that have arisen among evangelicals in the twentieth century.

(2015-09-01). I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship (pp. 167-168). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

So when Scot McKnight was criticizing the scholarly methods used by his peers to investigate Jesus he was not calling for them to turn their backs on fallacious “criteriology” and turn towards the methods of other professional historians (such a turn would have meant a revision in even the very questions they asked as historians) but he was, rather, declaring that historical inquiry was not capable of uncovering very much of relevance for the Church.

As a Gospels specialist I entered into the historical Jesus debates, first with an invitation from Craig Evans and Bruce Chilton to sketch the teachings of Jesus in the context of his mission to Israel (A New Vision for Israel) but then even more intensively in a book called Jesus and His Death (Baylor University Press). Two things happened to me — at the deepest level of my being — through that decade of study. First, I became convinced the historical method used in historical Jesus studies yields limited conclusions. My “aha” moment was sitting at my desk realizing I can prove that Jesus died but I can never prove that he died for my sins; I can prove that Jesus asserted that he would be raised from the dead but I can never prove he rose for my justification. . . .

Interesting that the two details that McKnight singles out as subject to unequivocal “proof” are the two points central to the Christian faith itself. He follows by affirming the importance of traditional Church belief over the findings of historical studies. . .

[S]econd, I came to the conclusion that the church does not need historical Jesus studies. Mind you, I need to define what I’m saying. By “historical Jesus studies” I mean the exercise of historiography on the ancient sources in order to determine what Jesus was really like over against what the Gospels say and what the church’s creeds have claimed. In other words, to do historical Jesus studies by definition begins by questioning the veracity and historical authenticity both of the Gospels themselves and what the church has always confessed. . . .

I have come to the conclusion that the Gospels are the church’s portrait of Jesus, and that portrait is what the church most needs.

(2015-09-01). I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship (p. 168). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

“We are not historians; we are Christians.”

I tell my academic friends at times that “We are not historians; we are Christians.” They sometimes act like I’m nuts and at other times like they know what I’m getting at but wish I’d not say it so forcefully. My point is not that we don’t have to be skilled at the craft of historiography, about which I wrote in Jesus and His Death, but that our aim is not simply historical discovery. Instead, our aim is to speak to the church as Christians who worship the Trinity.

(2015-09-01). I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship (pp. 168-169). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

What Scot McKnight is regretting here is the gap between what biblical scholars write for one another as members of the academy and how much of this filters down to pastors and through pastors to their congregants.

Ah yes — that’s a lament I well understand. It was the same regret that was one of primary motivations for starting Vridar. Science has its popularizers of current developments but what I was reading by biblical scholars was not getting out to the general public. McKnight’s lament, of course, was fed by other hopes.

This is a pity, and it’s a pity because believing scholars are called to serve in the church but if all their intelligent work is for the sake of the academy very little of it will be passed on to the church. I am committed to aiming all my writings at the church.

(2015-09-01). I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship (p. 170). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

Presumably scholars like Larry Hurtado and Richard Bauckham feel the same way and this is the reason they sometimes appear to pour scorn on even the mildly liberal scholarship found in the Jesus Seminar.

Reading the following one might think it impossible for such a scholar to ever approach historical Jesus studies through the same sorts of sound critical methods — beginning with a widely informed analysis of the nature of the sources themselves — as we expect of historians generally. But then again, we do have Thomas Brodie who did begin with a critical source analysis widely informed by the literary and philosophical culture of the times, who concluded that they supported only a literary-theological figure of Jesus, and who still maintains a deep Christian faith.

I am not infrequently asked to respond to Christians who are losing their faith, and often enough their letters to me are notes of despair and fear. The first thing I try to do is distance their faith from what they learned, from the theology they have embraced, and try to get them to think about Jesus — the Jesus of the Gospels — what he taught, what he did, what he reveals about God, and, if he is God, what he reveals God to be like. I do this because over the four decades of my life in the academy, the first decade more as student than professor, it is Jesus to whom I have turned when my faith begins to wane. I have found one of his words to be constantly assuring: “I am the Bread of Life.” He has been, he is and always will be.

. . . . [W]e are handing on our faith to our children and their children — in the context of worship and fellowship. What is going on there is propped up by an academic career of teaching and writing, but what goes on transcends the academic career. It is there — under the preached Word and in the Eucharist — that Jesus’ death and resurrection bring forgiveness and justification. When my grandkids become adults and begin to think about me as their grandfather I want them to say that their grandpa was always talking about Jesus, even on the golf course or during baseball games.

(2015-09-01). I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship (p. 171). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

McKnight said: “My ‘aha’ moment was sitting at my desk realizing I can prove that Jesus died.”

Actually, all we can glean from Paul about Christ’s death is that “Christ died according to scripture,” which either means (I) Paul contended that Jesus’ death “fulfilled scripture,” or (II) Paul discovered Jesus’ death through an allegorical reading of scripture (such as the implicit piercing of hands and feet, Psalm 22:16b). Whether (I) or (II) is correct makes little difference for the writing of history because both options show the writer at that point had theological intentions, so it is possible Paul invented the account of Jesus’ death to serve a theological purpose. It is for the same reason biblical hermeneutics excludes miracle stories from belonging to the portrait of the historical Jesus.

John, I misplaced my reply to you.

I think Paul is telling us that Cephas was the one who discovered Jesus’ death but rather than it being an allegorical reading, it was a literal reading of an allegory. In the Romans Doxology, Paul writes “according to the revelation of the mystery that was kept secret for long ages but is now disclosed, and through the prophetic writings is made known to all the Gentiles”. It is like they thought there was real history hidden within the allegory. So “according to the scriptures” was “Christ died for our sins” would come from the Suffering Servant (Isaiah 53:5, 12), “and that he was buried” (Isaiah 53:9), and “he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures” (Hosea 6:2).

But I think Paul came up with the crucifixion bit. It seems to me that if he was saying that Cephas, the twelve, the 500, and James had actually witnessed a resurrected Jesus, he would have just cited their testimony as proof of the resurrection rather than arguing rather poorly for it in 1 Corinthians 15:12-34. He even pre-refuted Pascal’s Wager in verse 19.

I think when he asks in Galatians 3:1, “You foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you? It was before your eyes that Jesus Christ was publicly exhibited as crucified!” Paul refers to James and Paul who he spent the first two chapters discrediting as the “Circumcision Faction”. Paul then goes on to spell out his crucifixion formula. It appears to me that it was the Circumcision Faction vs. the Crucifixion Faction.

All good points. (I think in your last paragraph you mean James and Peter [not Paul] as the “Galatians.” I had not thought about Gal 3:1 as addressing them but you could be right!)

Yes, the second Paul was supposed to be Peter (or Cephas).

Notice that in Galatians 1:1, Paul states that he is sent by the Lord as he does in other letters but also emphasizes that he is not sent by human authority. He notes in Galatians 2:12 that James sent certain men to Antioch and identifies them as “the circumcision faction”. In Galatians 2:6, he mentions the “acknowledged leaders” or “pillars” with disdain as not meaning anything to him and identifies them three verses later as James, Cephas, and John. Paul is in full sarcasm mode in Galatians 5:12 where he wishes they would go the whole way and castrate themselves. So it seems to me that when he calls James “the Lord’s brother” in Galatians 1:19, he is heaping more sarcasm on James for assuming the authority to send people places the way the Lord sends Paul on missions.

Hi.

The question is: what can we claim about Jesus’ death if we are doing responsible (as opposed to speculative) history. Paul says (see 1 Cor 15:3-4), for him, either Jesus’ death fulfilled scripture, or his death was learned about through reading scripture. Therefore, for Paul, the claim that Jesus died is a theologically motivated claim. In the same way we “set aside” miracle stories when reconstructing the historical Jesus because the authors may have had theological motives for inventing them, we also “set aside” reported events that are grounded in Hebrew scripture (such as Matthew presenting Jesus as “The New Moses”) because they too might have been invented by the authors for theological reasons. In terms of history, we can’t know whether Jesus was crucified or not, so we simply eliminate that element when reconstructing the historical Jesus. Likewise, since Paul may have simply learned Jesus died through a reading of scripture, we can’t know if Christ actually died at all or was just a myth, so we don’t mention Christ’s death at all in a responsible (as opposed to speculative) reconstruction of the historical Jesus.

Paul mentions “Jesus”, “Christ”, “Jesus Christ”, and “Christ Jesus” 300 times in about 1500 verses of the least disputed epistles, mostly religious awe, but there are a few dozen “facts” given. When Paul tells us in Galatians 1:11-12 that he didn’t get the gospel from a human origin but by revelation, we can believe him because every fact claim he makes about Jesus, past, present, and future, seems to come from Hebrew scripture, specifically from books he quotes from in other places. That holds true for the other epistles except for 1 Timothy and 2 Peter which appear to repeat information about Jesus from the gospels.

It appears that the first century Bible authors had no first century information about Jesus.

“We are not historians; we are Christians.” They sometimes act like I’m nuts and at other times like they know what I’m getting at but wish I’d not say it so forcefully.

That statement well summarizes Historical Jesus studies, past, present, and future.

At all points you must pretend that you’re a historian and that your religious bias is supposedly irrelevant. No real historians are fooled by this ruse, but most Christians are.