“What do the Charlie Hebdo murders and the rise of the Islamic State owe to Islam? It would be comforting to insist, as many have done, that they owe nothing at all; but Holland, in the inaugural Christopher Hitchens Lecture, argues that the truth is more complex. The best way to combat jihadism, he proposes, is to recognise the centrality of Muhammad to Islam – and that he comes in many forms. There is the moral leader who swallowed abuse peaceably; and there is the war leader who ordered people who insulted him put to death. How best, then, to de-radicalise the Prophet? Tom Holland is author of In The Shadow of the Sword, Rubicon, Persian Fire, Millenniumand the new translation of The Histories by Herodotus. Chaired by Katrin Bennhold of the New York Times.” — from the Hay Festival program.

Denouncing Islamic State as not representing “true Islam” is a well-intentioned declaration but counterproductive and seriously problematic, according to historian Tom Holland in the inaugural Christopher Hitchens Lecture at the May 2015 Hay Festival. The title of his talk is De-Radicalising Muhummad (available online).

What is wrong with these well-meaning efforts to defuse anti-Islamic tensions?

What it does is imply that there is a normative, authentic Islam, one that embodies ideals that are perfectly compatible with liberal, secular Britain, and then there are misinterpretations of it, distortions of it, that are not really Islam at all. . . . .

Playing the same lethal game as Islamic State

By denying the title of Muslims to Islamic State Western governments are actually playing the same lethal game as the Islamic State themselves. Because what the Islamic State do is to condemn other Muslims as either apostates or heretics — the better then to justify their elimination.

I really don’t think it is for Prime Ministers or Home Secretaries to play that game. Because once you take it on yourself to define what is or isn’t authentic Islam then you are buying into the notion that such a thing as authentic Islam actually exists.

Now if you’re a believer of course that’s fine. You will accept that indeed Islam was given to you by God and therefore it does have some absolute Platonic essence.

But if you’re not a believer then a religion is just like any other manifestation of human culture. It’s something that is porous, variable, forever mutating, and evolving. It’s a dialogue between people in the present and an inheritance of texts and traditions and people can choose what of those texts and traditions they wish to emphasise.

So it’s not like religion is the equivalent of a radio station set with a dial and you can definitely find it. It’s a whole series of points on a bandwidth.

That understanding ought to give us hope, however long-term it may have to be. It certainly ought to contribute to a lessening of social prejudice and a promotion of constructive ways of addressing the problem of violent Islamic groups and individuals.

And obviously what a definition of an extremist is, what a radical is, will depend where you stand on that bandwidth. Because it cannot be emphasised enough that jihadists do not think of themselves as extremists. To them, it’s us, the comfortably secular and liberal kind of people . . . who are the extremists. Jihadists see themselves as models of righteous behaviour. They see themselves as doing God’s will as expressed in the pages of his holy book the Koran and the sayings of his prophet Muhammad. And they also see themselves as obedient to something else — to the example of Muhammad. The Koran is absolutely explicit about this. In the Messenger of God it says you have a beautiful example, an example to follow.

And so it does matter then, to jihadis no less than to the vast majority of Muslims who would never in a million years set about destroying the antiquities of the Near East, or taking sex slaves, or murdering those who mock the Prophet. But sanction for what they do is indeed to be found within the various biographies and traditions that are associated with the Prophet.

So what does Tom Holland see as the appropriate response?

Why try to de-radicalize jihadis without also trying to de-radicalise the Prophet who as the “beautiful example” set before them by God is bound to serve them as their surest inspiration and role model? To do so is I think essentially to put a sticking plaster over a deeply buried thorn.

Non-Muslims can also contribute

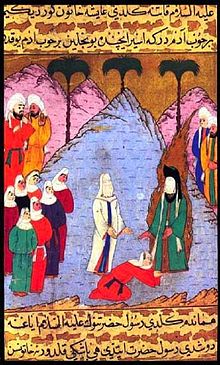

Holland says that it is only in recent history that an interest in the literal interpretation of the life of Muhammad has surfaced as a major Islamic interest. Muhammad had long been understood predominantly as the spiritual figure, the symbol of God’s will, the intercessor at the last judgement, etc. (I was reminded of the way Christians have generally tended to view Jesus Christ — as the mediator and saviour figure — with little thought given to uncovering what we can about the historical person.)

The change came about as a result of Western influence via imperialist encroachments into the Muslim world. Western scholarship was geared towards getting back to the historical roots and what we could reliably know about a religion’s origins. The earliest sources were deemed to be the most reliable for this purpose.

Westerners who complain that what Islam needs is a Reformation (as Christianity had) overlook the fact that what we are seeing today is a “Reformation” occurring in Islam right now. The Salafist movement is seeking to get back to the roots of Islam. When we roll our eyes at those naive ones who drop all to go off and join Islamic State we are the equivalent of sixteenth century Catholics who looked down their noses at those who left to join Protestantism.

This all sounds very depressing. Holland argues that part of the solution needs to come from Muslims themselves who can return the focus to the spiritual place of Muhammad as the intercessor and symbol of God’s heavenly will. But non-Muslims can also contribute.

Scholars of Islam increasingly are conceding that we know even less about the historical Muhammad than we do about the historical Jesus. What we know about Muhammad largely comes from writings flourishing from about 200 years after his death.

Is Islam a religion of peace or of violence? Of course it’s both. We can find passages in the Koran to argue both ways. What the evidence we have indicates is that the life of Muhammad was created to justify political interests of the day. Islamic warriors emphasised the military facets of Islamic teaching to justify their military programs. We can see that Muhammad’s traits have been created to represent later political interests.

One might even compare the early writings about Jesus. Critical theologians are generally comfortable with the idea that each gospel represents a Jesus who embodied a particular subsequent theological interest of “the church”.

Understanding the original context of the biographical details

In other words, the Prophet was not the model from which religious precepts were drawn; rather, it was the reverse: the Prophet was created out of those precepts the most served the interests of the prevailing powers of later generations.

The first accounts of Muhammad taking Aisha as his bride when she was only six years old and then consummating the marriage when she was nine years of age did not faze the earliest narrators or commentators in the least. Why?

Modern Muslims can explain this by arguing that the cultural mores of the time were quite different from those of today; some even argue that in the heat of the Middle Eastern regions back then girls matured earlier than they do today. But that kind of argument opens another can of worms: if one detail of Muhammad’s life is obsolete because of changing cultural values then how many other Islamic precepts must fall by the wayside?

An alternative approach is to understand the real interests of the original “biographers”. They were not interested in constructing a historically fact-filled authentic historical account as modern biographers and historians tend to want to do. They were not fazed by the details of what today has been relegated to the crime of pedaphilia. The reason is that the details of Muhammad’s marriage to Aisha had a political message, not a biographical one. Aisha’s father became the first caliph to succeed Muhammad. The point of describing Aisha’s prepubescent union with Muhammad was to emphasise that she could not possibly have been associated with any other man and that her union with Muhammad was unique and pure.

My own thought by way of comparison: critical scholars or liberal Christians believe Mary was really a virgin when she gave birth to Jesus. The story of the virgin birth was not meant to inform us about literal historical facts but to indicate the special and unique place of Jesus between God and the rest of humanity.

This is the sort of critical understanding that, if emphasised over the interest in anachronistic literal readings of the ancient texts, can help contribute towards a religious understanding that deplores literalism and values contrary to normative ethics today.

That is my take on what Tom Holland’s message is. I don’t know what else can be done — apart, of course, of “the unthinkable”: advocating for national-political policies that are informed by genuine understanding and humanitarian values.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!