The reality of Palestine’s long history from the Bronze Age to the present has been lost behind the myths of the Bible.

The reality of Palestine’s long history from the Bronze Age to the present has been lost behind the myths of the Bible.

Think of Palestine’s past and images of Israel displacing the Canaanites from around 1200 BCE, establishing a united kingdom, even an empire, under King David and then his son Solomon slip easily into our minds. We think of the divided kingdom: apostate Israel in the north ruled from Samaria and Judah in the south with its Jerusalem temple. We know these kingdoms were removed by the Assyrians and Babylonians by around 600 BCE and that the Jews returned once again after a period of captivity.

And they re-returned to “the land of their fathers” to “re-establish the Jewish State” as proclaimed in Israel’s Declaration of Independence of 1948. The historical right of the Jews to the land of Palestine remains evident today to possibly most Christians and anyone taught this historical outline.

Archaeological-Historical Periods in Palestine

- Early Bronze Age 3150-2000 BCE

- Middle Bronze Age 2000-1550 BCE

- Late Bronze Age 1550-1200 BCE

- Iron Age 1200-587 BCE

- Persian 538-332 BCE

- Hellenistic 332-63 BCE

- Roman 63 BCE – 330 CE

- Byzantine eras 330-636 CE

- Early Caliphates 636-661 CE

- Umayyad, Abbasid, Fatimid, Seljug 661-1098 CE

- Crusaders 1099-1291 CE

- Ayyubid and Mamluk 1187-1517 CE

- Ottomans 1517-1917 CE

- British 1920-1948 CE

- Israeli 1948 – present

The question we might ask, then, is what is the history of the Palestinians? The biblical narrative leaves them no room for a history in the land. Are they late trespassers? Are they rootless Arabs with no genuine attachment to any land in particular?

Until his retirement Keith Whitelam was Professor and Head of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Stirling and Professor and Head of the Department of Biblical Studies at the University of Sheffield. His recent publication, Rhythms of Time: Reconnecting Palestine’s Past, surveys the archaeological evidence for the history of Palestine from the Bronze Ages through to the end of the Iron Ages and compares what he sees with the Palestine from more recent times according to travelers’ reports and current geo-political maneuverings.

He concludes that our Western view of Palestine’s history has been determined by the biblical narrative and conflicts with the archaeological evidence before us.

The past matters because it continues to flow into the present. However, Palestine has been stripped of much of its history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is as though Palestine only came into being with the British Mandate (1920-48) and came to an end with the declaration of the modern state of Israel (1948). The growth of towns, the shift in villages, or the population movements of three millennia before have become divorced from this ‘modern’ Palestine. (Kindle Locations 42-46).

Whereas others who have been gaining their independence from imperial domination ever since the nineteenth century and especially since World War 2 have been able to construct their own national histories as an essential part of their national identities,

what is peculiar here, and possibly unique, is that with the retreat of the European powers, and Britain in particular, the post-colonial history [of Palestine] that was written was not undertaken by the indigenous population but by a new colonial power. It was a reflection and reinforcement of what had gone before. It was a colonial Zionist narrative, which as a European enterprise in its origins, simply reiterated and reinforced the notion of external conquest and the bringing of culture and civilization to the region.

Palestine lost it history first to the European imperial powers and then to a Zionist construction of the past which rapidly became its national narrative. The history of Palestine became embedded under two layers of imperial and colonial history; layers which are so thick that they are almost impenetrable. (Kindle Locations 48-53, my bolding and formatting in all quotations)

Since then we have heard it said that the Palestinians are an “invented people” (Newt Gingrich) and that Palestine before the modern State of Israel was a “land without a people” (Golda Meir, Joan Peters).

Whitelam recognizes the consequences of this belief:

What underlies his claim is a very important principle: the idea that a nation without a past is a contradiction in terms. If the Palestinians do not possess a past, they cannot possess a national consciousness or be a people. Therefore, they have no right to a land or a state. (Kindle Locations 69-71)

I began by outlining the images of the history of Palestine that come to our mind most readily today. Keith Whitelam’s book gives readers the reason or the historical background that explains why these images are so dominant in our culture. Ever since the eighteenth century, even back long before to the days when the early European maps were being drawn, western Christian nations have seen Palestine as “culturally theirs”, or as the land of “their religious heritage”. (See the seventeenth century map of Palestine below and Whitelam’s commentary.)

Facts that contradict this religious myth are denounced even today. The Israeli archaeologist, Ze’ev Herzog, was denounced by Israel’s Minister of Justice and Deputy Prime Minister for undermining Israel’s security and giving aid to Israel’s enemies when he published what had become an accepted view among many archaeologists at the time: that there was no Exodus or conquest of Canaan and that at the very best the kingdom of David and Solomon was a very small tribal affair.

What our traditional view of Palestine’s history overlooks is the daily lives and routines of the ordinary people in the land through the millennia: their adaptability to maintain security of their livelihoods through the changing and often unpredictable seasons, the shifting economic fortunes of the various urban and rural centres, and the catastrophes from time to time of warfare, or natural disasters such as epidemics or climate shifts.

The so-called great men, monarchies, and imperial powers have followed on from one another in the region, attracting most attention like the froth of the waves breaking on the shoreline. Yet underlying this surface movement . . . was a substratum that moved slowly to the rhythms of time absorbing and dissipating the effect of the waves.

It is this story, an essential part of Palestine’s past, that was ignored by western visitors and scholars in favour of the events and characters described in the Bible. (Kindle Locations 302-306)

Whitelam asks us to look beyond the names of kings and conquerors through to the archaeological signs of a humanity with the same sorts of hopes, aspirations, fears that we all share.

Yes, the archaeological evidence does inform us of changes to the lives of the inhabitants of the region around the 1200 BCE mark. There had been an economic collapse in the decades that mark the close of the Bronze Age. Cities no longer provided the security and income the rural populations needed so many of them moved to settle away from the plains and old trade routes and to live in smaller communities in the hills.

What one needs to notice, Whitelam reminds us, is that far from being a unique moment in Palestine’s history we are seeing events at the end of the Early Bronze Age being mirrored. The Iron Age to follow (thought of as the period of Israel’s homeland) was not unique, either, but reflected the rise of the Middle Bronze Age and foreshadowed the future revivals of Roman and Byzantine Palestine.

Signs of such shifts are part of the pattern of Palestine’s history over the millennia. As trade returns, say to the coastal cities, rural populations are again attracted to these centres; as neighbouring imperial powers encroach on the region, new economic and infrastructural realities and new trading and security priorities shift the economic and demographic patterns again. The rural peoples were adaptable and through their mix of agriculture and pastoralism they were able to adapt, even move to new areas, to survive.

Whitelam throughout the book demonstrates that there is nothing unique about the Iron Age. There is no reason arising from the archaeological evidence to interpret any of these shifts as indications of new ethnic races invading or infiltrating and replacing the indigenous inhabitants. Yes there were new migrations from time to time but there is no indication that one ethnic group ever replaced another. Yes Jerusalem did at one time rise to some prominence but so did many other cities in the region, and generally to greater dominance.

Changes in the economic fortunes of the different regions, in the demographic patterns, in the relative levels of prosperity and destitution, in political fortunes, were as “rhythmical” as the cycles of the seasons and the monthly patterns of agricultural life.

Whitelam finds literary testimony to these changing fortunes in both biblical texts (Genesis, Ruth, Isaiah, Lamentations) and Canaanite literature (Armana letters, the Ugarit story of King Keret, the Gezer calendar, the fourteenth century BCE Baal poem) as well as in travellers’ reports through the ages (Ibn Battutah, Claude Conder, Rev William Thomson, Edward Robinson, Eli Smith).

Suddenly we see the growth of hundreds of small, rural villages in those regions which had been sparsely populated in the Late Bronze Age and which were removed from the direct control of the major towns. The countryside became dotted with small, unwalled villages, most newly established in the twelfth century BCE, arranged in a variety of patterns, with many located on hilltops near arable land. Again, this is not something new or unique in the history of the region. Nor is it a pattern of settlement imposed from the outside by invading Israelites. It is a privileged glimpse of important rhythms that resurface from time to time to remind us that they are ever present, even if not always visible. (Kindle Locations 776-781)

And again,

Palestine regularly suffered settlement contraction only to see a revival in subsequent periods. The Iron Age, therefore, was not a unique period in the history of the region. The revival of early Iron Age Palestine in the countryside was part of a much wider regional response by rural and pastoral groups to the decline or disruption of towns. It is part of the rhythms of Palestinian history.

The fact that we glimpse similar responses in many different areas to the general recession that afflicted the eastern Mediterranean shows that the changes in settlement in Palestine were not primarily the result of new groups coming from outside and taking over the land. That this kind of demographic shift is not unique to Palestine, but is a common response of rural communities, can be seen from the way in which populations throughout southern Europe, Greece, Anatolia, and Syria-Palestine responded to the disruptions of the Mediterranean basin at the end of the Late Bronze Age.

Similar conditions elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean basin provoked very similar responses from the rural population. Central and southeastern Europe in the twelfth century witnessed a proliferation of small, rural settlements, comprising a few buildings with silos for grain storage, situated on good agricultural land and devoted to farming and herding. We see similar shifts in settlement away from the exposed lowlands to the protection of the highlands from Greece to Syria.

What we are witnessing is the struggle to survive and the harsh choices that have to be made in the face of economic recession and disruption. (Kindle Locations 1045-1056)

But what about the Israelites? If you are still asking that question, Whitelam replies:

We simply cannot know how these villagers referred to themselves and others in neighbouring villages or what the designations they used might signify. Nor are these particularly important questions. The modern nationalist obsession with such labels—the attempts to impose ethnic difference—is not appropriate for the ancient past. (Kindle Locations 1084-1086)

It is not easy to think of Palestine’s history this way. Whitelam’s descriptive powers and extensive knowledge help.

Surveying the thousands of years of stones, bones and artefacts since the early Bronze Age (from ca 3150 BCE) Whitelam enables readers to identify an integrated history of natural rhythms, a “constant ebb and flow in the fortunes of individual towns” along with the rural regions, always “in the process of growth, stagnation, or decline.”

The people of the countryside accordingly through the same periods adapted and regularly moved in order to survive. “Mobility and adaptability” have been the constant traits of the those engaged in agriculture and pastoralism through the millennia.

Yet the idea that the history of the land was broken by the incursion of the Israelites who established a unique, unified nation-state and world-class empire over most of Palestine and Syria is

a belief that is so deeply ingrained in western popular and political thought that it has become extremely difficult to imagine the past in any other way. (Kindle Locations 1140-1141)

It is that very scenario that would indeed

be completely out of keeping with the history of the region (Kindle Locations 1146-1147)

The very notion that such a kingdom and new civilization and ethnic group took control to break the patterns of the past should, Whitelam advises, cause us to re-examine our perceptions and the way we were reading the evidence. There is no evidence for political centralization or competing states with capital cities and highly hierarchical structures of administration

Yet this vision of the past is little more than a mirage. Little, if any, attention has been paid to the rhythms of Palestinian history. It is only as our perspective changes, as we concentrate on the rhythms of Palestinian history, that the vision dissolves.

Only then do we see how the structures of the Bronze Age towns were maintained and revived with the increase in population and the revival of the economy as the Iron Age progressed.

Rather than this being some unique turning point in the history of Palestine—a justification for Western imperial control or the current Israeli government policies of occupation—it becomes an integral part of the rhythms of Palestinian history that continue to the doorstep of the present. (Kindle Locations 1148-1153)

The biblical vision we have of Palestine founders again on the evidence for the supposed deportation of the population of Judah to Babylon in the sixth century. Population did decline in the immediate vicinity of Jerusalem but many places elsewhere there was no such decline. Nebuchadnezzar did not uproot the general population.

The end of the Iron Age again illustrates the rhythms and patterns of Palestine’s past, the differing responses of its fragmented landscape and its inhabitants to the deep seated movements of history. It is not a special period—to be set apart as though it is something unique—but one that is integral to the history and rhythms of Palestine’s past. (Kindle Locations 1638-1641)

What of today’s Palestine? How does today compare with the past?

The increasing interest taken in the region by the Assyrians, and later the Babylonians, was fuelled by the desire to control, stimulate, and exploit the arteries that carried the life-blood of trade. It is a recurrent theme, repeated over many centuries, which continues into the present day. . . . Palestine has always been of interest to those powers that aspired to global domination. (Kindle Locations 1745-1747, 1754)

Becoming aware of the “deep history” of Palestine that is found at the level of those people whom historians, focused as they are on kings and empires, have so often made invisible clarifies our vision.

An integrated history of Palestine bestows dignity on the silent voices and actions of the many: the constant movement of pastoral groups across so-called boundaries, the movement back and forth to the fields each day, the transport of goods on small craft along the coast, or the movement of flocks and herds following the rhythms of time.

If we view the mosaic that is Palestine over the centuries, despite the almost constant threat of empire, it is a region that is difficult to subdue and control, as the present demonstrates so clearly. It is ever resistant to state or imperial control, finding ways—some times through direct conflict but more often than not by subtle ways of non-participation—to maintain its local identities and autonomy.

As such, even during periods of strong central control, it has looked persistently for opportunities to throw off the shackles of empire. Despite the colonial present—the overwhelming use of force and terror to subdue the indigenous population or imperial constructions of the past— Palestine’s past can still be measured differently.

The adaptability of the inhabitants in the face of the overbearing power of fate and the hostility of civilization . . . along with the connectivity and ever-changing configurations of the different regions of Palestine have governed this history. It is the rhythms of time that have guided what the vast majority of the population have done, even up to the present. It is when we take this perspective that we can begin to see what was important in Palestinian history . . . (Kindle Locations 1808-1819)

–o0o–

But to understand just how deep-seated these ideas and images are and why they are so difficult to dislodge, we need to go back a few centuries. John Speed, the English cartographer, produced an atlas in 1611 called The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain which included detailed maps of the counties of England, along with those of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. It was later expanded in 1627 with A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World, containing maps of other parts of the world. Speed included a map of Palestine at the very end of the volume.

Although in the atlas he claims to be ‘presenting an exact geography of the kingdom of England, Scotland, Ireland and the Isles adjoining’, it is noticeable that his map of Palestine features the route of the Exodus, the land divided among the tribes after its conquest and an inset of Jerusalem. This is not a real place with contemporary inhabitants, towns or villages but an imagined land. He has also drawn it as though it is a typical English county.

Like his maps of the various English counties, it includes an inset of its major town and is decorated with the same symbols for towns and villages, historic events, ships and large fish. The ship and large fish is a recurrent image in these maps, alluding to the story of Jonah and the whale in the Bible. Significantly, the ship off the coast of Palestine is flying the English ensign. Speed describes Great Britain as ‘the very Eden of Europe’, a land flowing with milk and honey, and says there is no land like it except that conquered by Joshua and divided among the tribes.

In Speed’s atlas, Palestine is already part of the empire . . . . (Kindle Locations 94-106)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The Palestinian people have a history, of course, and the Palestinian Arabs also have a country; a country whose charter was defined and created expressly for them and not for Palestinian Jews. It is called Jordan today, and for many decades it was accepted knowledge that Jordan was Palestine and Palestine was Jordan.

On August 23,1959, the Prime Minister of Jordan stated, “We are the Government of Palestine, the army of Palestine and the refugees of Palestine.”

King Abdullah, at the Meeting of the Arab League, Cairo, 12th April 1948: “Palestine and Transjordan are one, for Palestine is the coastline and Transjordan the hinterland of the same country.”

Prince Hassan, brother of King Hussein, addressing the Jordanian National Assembly, 2nd February 1970: “Palestine is Jordan and Jordan is Palestine; there is one people and one land, with one history and one and the same fate.”

“Jordan is not just another Arab state with regard to Palestine but, rather, Jordan is Palestine and Palestine is Jordan in terms of territory, national identity, sufferings, hopes and aspirations, both day and night. Though we are all Arabs and our point of departure is that we are all members of the same people, the Palestinian-Jordanian nation is one and unique, and different from those of the other Arab states.”

— Marwan al Hamoud, member of the Jordanian National Consultative Council and former Minister of Agriculture, quoted by Al-Rai, Amman, 24 September, 1980

You missed Whitelam’s point entirely, to the point where your comment is off-topic. Try reading the post again.

Whitelam’s The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History is of interest, as well.

http://www.amazon.com/Invention-Ancient-Israel-Silencing-Palestinian/dp/0415107598/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1423792773&sr=8-1&keywords=whitelam

I am not addressing Whitelam, I am addressing Neil’s pre-lim.

You spout usurping impostor European zionist propaganda. Its quite obvious they want to liberate Palestine from the river to the sea – not just the bit the area they call Jordan. Your basic lack of understanding English is very telling.

“Population did decline in the immediate vicinity of Jerusalem but many places elsewhere there was no such decline.”

-Name three. 😉

“There is no reason arising from the archaeological evidence to interpret any of these shifts as indications of new ethnic races invading or infiltrating and replacing the indigenous inhabitants.”

-I think more DNA study is needed, just to make sure of this.

“Nor are these particularly important questions.”

-I think they are. Ancient Near Easterners certainly had concepts of ethnicity, and I think it’s important to know how such concepts may have impacted their behavior.

Also, since I’m typing this from a tablet, I’ve just discovered the Sweet Captcha works terribly on touchscreens. Works great with desktops and laptops, though.

“I think more DNA study is needed, just to make sure of this.”

Why do you believe that DNA studies are of any value at all when there is no DNA from the time in question?

“Ancient Near Easterners certainly had concepts of ethnicity, and I think it’s important to know how such concepts may have impacted their behavior.”

And you know this how? Shaye Cohen in his The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties argues that the Greek word that we associate today with referring to the Jewish ethnic originally was meant to refer purely to the geographic origin of a person as being Judea. The meaning of words change over time, and we need to be careful not to retroject our modern understanding of words today onto ancient people’s. That’s Whitelam’s basic point: biblical scholars are viewing the archaeological evidence through a modernist lens and thereby unwittingly constructing an “ancient history” that never happened.

http://www.amazon.com/Beginnings-Jewishness-Boundaries-Uncertainties-Hellenistic/dp/0520226933/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1423793457&sr=8-1&keywords=beginning+of+jewishness

There certainly is very valuable DNA evidence from earlier times and wetter places than Iron Age Palestine, as Razib Khan has pointed out in recent posts. I don’t know the burial finds in Palestine well enough to say whether there is any for our periods and locations of interest. What are Nubian, Egyptian, Sherden, Assyrian, etc. other than ethnic terms? And what do you consider the differences between the archaeological Philistines and their predecessors as indicating?

E. Harding:

Whitelam’s far more detailed book on the archaeology is on it’s way to me and I will consult that for details. (I think in earlier posts I did cite some details to this same point.) Meanwhile I would greatly appreciate it if you could cite any evidence you feel contradicts Whitelam’s statements, especially those I’ve repeated in this post. I think I have asked you for these sorts of details in earlier comments of yours but you may not have noticed them. I do hope you see this request. If I am being misled by fallacious claims I want to know.

I see your response now. The most detailed archaeological volume on the Babylonian period in Palestine that I know of is Oded Lipschits (a noted plagiarist of G.M. Grena on another issue)’s Fall and Rise of Jerusalem, published a decade ago. Avi Faust (not always the most competent scholar, I might add) has a more recent volume out called Judah in the Neo-Babylonian Period: The Archaeology of Devastation. Some of their articles on the period are available on their academia.edu pages. Since academia.edu seems to be down right now, I encourage you to look at these papers later. From Table 4.3 of Page 270 of the Fall and Rise of Jerusalem, you can clearly see that the only area of Judah Lipschits believes did not fall significantly in population between Iron IIC and the Persian Period is the Northern Judean Hills (around Bethlehem). This seems reasonable, but possibly speculative. This was certainly the area that suffered least from Babylonian and Edomite attacks. Israel Finkelstein believes the population of Persian Period Yehud was some 50% lower than what Lipschits thinks.

http://web.archive.org/web/20140802160829/http://isfn.skytech.co.il/articles/Yehud%20Judea%20RB.pdf

I think Finkelstein estimates Judah’s population in the late seventh century BC to have been around 60 or 70 thousand in his The Bible Unearthed-much lower than Lipschits. Lipschits believes Judah’s population continued falling during the Persian period; I, for various reasons, do not believe this (with the exception of the destructions of Gibeon and Mizpah and the abandonment of Tell el-Ful).

Whitelam writes:

I wonder if the different views arise over a difference between “Judah” and “Palestine” — with Whitelam’s point addressing Palestine rather than being limited to Judah/Judea.

But am making some inquiries in the meantime.

I’m not sure of the situation in the coastal plan (though I’m certain it has been well-researched). Ashkelon and Ekron (Ashdod-Yam is still being excavated) were both destroyed during Babylonian rule. Dor was apparently abandoned. Hardly any Greek imports in Palestine dating to the Babylonian period have been found, making determining pottery assemblages of the period much more difficult.

books.google.ru/books?id=NcnPAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA76&dq=%22dor%22+babylonian+period&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ZnPkVOrPK4eoygOelYDwBQ&ved=0CCIQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22dor%22%20babylonian%20period&f=false

http://www.academia.edu/1057490/Between_Carmel_and_the_Sea_Tel_Dor_the_Late_Periods

The situation in Samaria during the 7th-3rd centuries BC is more murky than that in Judah due to the lack of destruction layers and historical records. On this, see Page 267 of here:

http://www.academia.edu/1070455/Temple_and_Dynasty_Hezekiah_the_Remaking_of_Judah_and_the_Rise_of_the_Pan-Israelite_Ideology

I’m wondering if Whitelam is referring to Galilee or anything else when he refers to “the north”. I also wonder what his source is.

The table you draw attention to in fact shows that the northern Judean hill area did not suffer the dramatic decline of other areas listed.

I am wanting to access the following references but it will take quite some time to do this.

On the variation of settlement decline/continuity in areas of Palestine beyond the immediate region of Jerusalem:

On the Judean territory being an exception to the drop in settlements with 25% increase in number of sites (mostly small unwalled settlements):

On there being 133 settlements with 71.5 hectares of built-up area in the southern hill country during 7th and early 6th centuries:

On there being a 65% increase in settlement in the north compared with decline in the southern and central regions:

Whitelam is arguing that the variations in patterns at the end of the Iron Age echo similar variations — declines of urban areas as rural centres relocate, some urban areas thriving as others are destroyed or decline — explicable in terms of shifting economic and security conditions.

Unfortunately I have only been able to locate two of the above references and want to read the remainder in order to assimilate the details.

More than other so-called “Minimalists,” Whitelam appears to be something of a lightning rod for the criticism of Zionists. He has even been accused of being anti-Semitic!

I think this criticism is misguided. Whitelam is not anti-Zionist, anti-Israel, or anti-Semitic. He’s pro-history in the most modernist sense (he is not post-modern by any means).

Whatever the history of Palestine was, Israel’s modern claim to sovereignty over its current territory does not rest on that history but on the pronouncements of modern Western states who configured the Middle East to be as it is today. Going forward, the legitimacy of Israel as a modern state must ultimately rest on how it treats people within its borders. Attempting to understand the actual history of Palestine outside of the literary construct of the Old Testament cannot harm Israel. Only Israel’s actions can do that. But if you believe the Old Testament is literal truth, you already knew that, right?

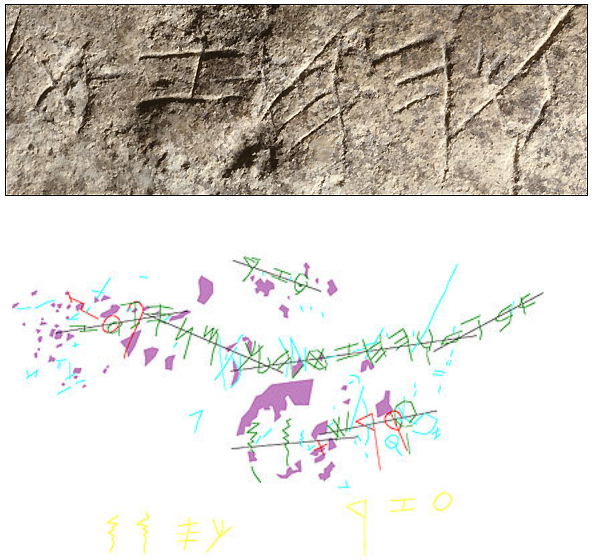

BTW, Neil, that unattributed tracing of the Zayit stone in your post was made by George Michael Grena, a Young Earth Creationist engineer. You should credit him.

I would need verification of what you say before I do that. I took the tracing from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zayit_Stone#mediaviewer/File:Tel-Zayit-Stone-Inscription.jpg

There it is explained:

I would need confirmation that that metadata against the source of the tracing is false before I attribute it to a name that comes to me via a third party blog comment.

E. Harding, I would really appreciate your answering my queries in response to your earlier criticisms. I do want to be sure I am not repeating falsehoods. I do not understand why you appear to have taken a belligerent stance against my posts. You suggest you know far more about the topic than I do so why you do not offer more details in response to my questions I do not understand. I am open to learning and correction.

http://www.lmlk.com/zayit/

Besides, this looks like one of Grena’s works. I think they’re made with a tracing program that he coded up. Grena’s Wikipedia handle is Funhistory. Mine is Eharding. I think I was answering your queries while you posted this comment. I do not have a belligerent stance against your posts; besides, I tried my hand at writing Palestine’s history the way Whitelam recommends back in early 2013 (although I never got around to doing much of anything with my blog since then). I can’t see anything belligerent in the tone of my original comment here (I tried to make sure my “name three” request was in good humor by adding a smiley). I do not know what you don’t know (though I can guess), so your lack of knowledge regarding this issue is a “known unknown” to me. :-S

BTW, the captcha is still impossible to use with touchscreens.

Apologies for misreading you. Waking up too early and with a headache this morning. Not good.

That’s a bummer about touch screens. Don’t know what can be done. Tim handles the captcha side of things.

I’ve finally figured out how to move the captcha icons with my finger. It involves pulling my finger a bit closer to a right angle while I’m beginning to drag the icon, hitting my finger exactly on the icon just before beginning to drag it, and only moving the icon sideways (upward or downwards means scrolling). That’s not exactly intuitive, but it works.

For best results, grip and drag the icon tightly with only a small part of the finger. I’m not counting, but I still think my failure rate is at or greater than 50%.

Good review, Neil!

Wasn’t Deane banned from this blog in a past life?

The land was not called “Palestine” during the Late Bronze and Iron Age – thus calling it “Palestine” is simply anachronistic – and even far more important: The People who lived in this land did not call themselves “Palestinians”, and they had absolutely nothing to do with those Arabs who call themselves “Palestinians” today…

The People who lived in this land did not speak Arabic; they were not Muslims (or Christians) and did not worship in mosques; they had a very different culture, and they had their own ethnic and national identities – including their own folk stories, myths, and national historical narratives – some of which are well known to us from the Hebrew Bible, since they were written and preserved by the local people of that time, who were called “Israelites” and “Jews” (=Judeans)…

Now, the funny things about lands, is that they have no ethnic or national history or identity of their own, and even no names of their own. Lands have no feelings, no memory, no religion, no narratives, they write no books and songs, and they couldn’t care less about identity of the people who are living on them – or what will be their fate. The only ones who care about such things are the People themselves. For example, those “Israelites” and “Jews” who have formed their national identity on this land you now call “Palestine”, actually bothered to cherish this land, to make their own narratives about their history in it, and to write their own books and songs on it and about it… In fact, they cherish this land so much, that even after many hundreds of years in exile they kept prayed three times a day to re-returned to “the land of their fathers” to “re-establish the Jewish State”…

So, what Keith Whitelam is actually trying to do in his books, is to steal the early history of the Canaanites in general, and the early history of the Israelites & Jews who lived in it (and who’s descendants have cherish its memory for 2,000 years in exile) in particular, and “give it to the land itself”. Then, by using the cheap “trick” of giving this land the anachronistic name “Palestine”, he is trying to re-steal this early history back from the land itself, and hand it over to some Arab population which have only very recently (after WW1) started referring to itself as “Palestinians”…

How very amusing, indeed…

Are you seriously suggesting that the Palestinians did not “cherish this land, to make their own narratives about their history in it, and to write their own books and songs on it and about it”? Seriously? Or are you simply lacking awareness of the history of Palestinian urban and agricultural life and their rich literary culture — and attempts since 1948 to destroy them?

What do you think happened to those “Canaanites” of ancient times if not conquest and conversion to a new religion and language as happens throughout history?

It also seems that you are unaware that when Zionism first emerged as a political-nationalist movement most Jews, most religious Jews who were praying for return, as you say, flatly opposed any idea of return in this day and age because they could not conceive of such an act without the messiah. So much for Jews pining to return to the land and suddenly rushing to do so when the invitation went out.

Neil, I’m sure the Arabs who lived on this land have loved & cherished the specific places where they were born and where they lived – *as individuals*. But, can you give me the name of one book that was written before the 20th century, by anyone who defined himself as a “Palestinian” author – a book which describes the “national narrative” of the “Palestinian People” in “The Land of Palestine”???…

Until you do, I prefer to believe the narrative of Zuheir Mohsen from the PLO:

“Between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese there are no differences. We are all part of ONE people, the Arab nation. Look, I have family members with Palestinian, Lebanese, Jordanian and Syrian citizenship. We are ONE people. Just for political reasons we carefully underwrite our Palestinian identity. Because it is of national interest for the Arabs to advocate the existence of Palestinians to balance Zionism. Yes, the existence of a separate Palestinian identity exists only for tactical reasons. The establishment of a Palestinian state is a new tool to continue the fight against Israel and for Arab unity.

A separate Palestinian entity needs to fight for the national interest in the then remaining occupied territories. The Jordanian government cannot speak for Palestinians in Israel, Lebanon or Syria. Jordan is a state with specific borders. It cannot lay claim on – for instance – Haifa or Jaffa, while I AM entitled to Haifa, Jaffa, Jerusalem and Beersheba. Jordan can only speak for Jordanians and the Palestinians in Jordan. The Palestinian state would be entitled to represent all Palestinians in the Arab world en elsewhere. Once we have accomplished all of our rights in all of Palestine, we shouldn’t postpone the unification of Jordan and Palestine for one second.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zuheir_Mohsen#Political_views

As for Canaanites: I think that what happened to those “Canaanites” is that they were either killed or assimilated among Israelites and Jews (in such why that all Jews today have some Canaanite ancestors) – And then, later on, they were gradually pushed out of their land by all kinds of occupiers, such as Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arab-Muslims, etc etc…

If you are trying to imply that they are the ancestors of the “Palestinian” Arabs, it seems that you are in contrast with the more genuine narrative that most Arabs who live in this land have about the origins of their families:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0B5hKbDdkU4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aYMviMHH0nc

It is also in contrast with some findings of modern-day genetic studies – and let me quote:

“The two haplogroups Eu 9 and Eu 10 constitute a major part of the Y chromosome pool in the analyzed sample. Our data suggest that Eu 9 originated in the northern part, and Eu 10 in the southern part of the Fertile Crescent. Genetic dating yielded estimates of the expansion of both haplogroups that cover the Neolithic period in the region. Palestinian Arabs and Bedouin differed from the other Middle Eastern populations studied here, mainly in specific high-frequency Eu 10 haplotypes not found in the non-Arab groups. These chromosomes might have been introduced through migrations from the Arabian Peninsula during the last two millennia. The present study contributes to the elucidation of the complex demographic history that shaped the present-day genetic landscape in the region.”

“We propose that the Y chromosomes in Palestinian Arabs and Bedouin represent, to a large extent, early lineages derived from the Neolithic inhabitants of the area and additional lineages from more-recent population movements. The early lineages are part of the common chromosome pool shared with Jews (Nebel et al. 2000). According to our working model, the more-recent migrations were mostly from the Arabian Peninsula, as is seen in the Arab-specific Eu 10 chromosomes that include the modal haplotypes observed in Palestinians and Bedouin. These haplotypes and their one-step microsatellite neighbors constitute a substantial portion of the total Palestinian (29%) and Bedouin (37.5%) Y chromosome pools and were not found in any of the non-Arab populations in the present study. The peripheral position of the modal haplotypes, with few links in the network (fig. 5), suggests that the Arab-specific chromosomes are a result of recent gene flow. Historical records describe tribal migrations from Arabia to the southern Levant in the Byzantine period, migrations that reached their climax with the Muslim conquest 633–640 a.d.; Patrich 1995). Indeed, Arab-specific haplotypes have been observed at significant frequencies in Muslim Arabs from Sena (56%) and the Hadramaut (16%) in the Yemen (Thomas et al. 2000). Thus, although Y chromosome data of Arabian populations are limited, it seems very likely that populations from the Arabian Peninsula were the source of these chromosomes. The genetic closeness, in classical protein markers, of Bedouin to Yemenis and Saudis (Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994) supports an Arabian origin of the Bedouin.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1274378/

As for Zionism and Judaism: It is a *fact* that Jews have prayed three times a day to return to their homeland, and even added few more such prayers on holidays. One of those prayers which are said three times a day, for example, is the “Kibbutz galuyot [=gathering of exiles] blessing”:

“תְּקַע בְשׁוֹפָר גָּדוֹל לְחֵרוּתֵנוּ וְשָׂא נֵס לְקָבֵץ גָּלֻיוֹתֵינוּ, וְקַבְּצֵנוּ יַחַד מְהֵרָה מֵאַרְבַּע כַּנְפוֹת הָאָרֶץ לְאַרְצֵנוּ. בָּרוּךְ אַתָה ה’, מְקַבֵּץ נִדְחֵי עַמּוֹ יִשְׂרָאֵל.”

“Blow a great shofar[=horn] for our freedom, and raise a banner to gather our exiles, and gather us together speedily from the four corners of the earth to our land. Blessed art you Lord, who gatheres the dispersed of Thy people Israel.”(this is the most accurate translation you will find on the web, btw).

The question of whether the return to the land is depended on the appearance of some “Massiah” – or not – is a secondary question, which is a matter for debate between religious Jews among themselves. However, although it is not relevant, it should be noted that the first Jews who laid the foundations for modern Zionist ideology and movement – before the time of Herzl and the first Zionist congress in 1897 – were actually all orthodox rabbis like the “Vilna Gaon” and his “Perushim” students, and like Rabbi Yehuda Bibas, Rabbi Judah Alkalai, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, Rabbi Samuel Mohilever, and more than few such others… We should also note that the “First Aliah” (=migration) of Jews back to the land of Israel in the 1800’s (before it became mandatory “Palestine”) was mostly of religious Jews (they are the ones who established the firs “Moshavot” like Petah Tikva); that it was the words and activity of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook who helped convince the British parliament to support the Balfour Declaration; and we should also note that most religious Jews in Israel today are considered “ultra-Zionists” and support the Israeli right-wing and settlement activities…

So, if you ask yourself “how come”, the reason is that most religious Jews never did object to the Zionist movement because of theological arguments about “messiah” or anything like that. Most were simply used to live where they lived – they had homes and jobs and families to support – and were too afraid to leave everything behind and go on a “messianic” adventure, and try to re-built their own country from scratch (many of those only changed after experiencing European Antisemitism in its full ugly scale); others just opposed “Zionist political movement” – because too many secular Jews took-over the Zionist establishments – but they didn’t reject the Zionist ideology, and, in fact, some ultra-orthodox Jews established competing organizations that also dealt with immigration and settlement in Palestine, such as “Agudat Israel”…

“suddenly rushing to do so when the invitation went out”?!? – Are you taking about Holocaust refugees who were pushed back to sea by British soldiers (Because Her Majesty’s government wanted to kiss the ass of the Arabs, so that they would stop supporting Hitler)???…

Oded Israeli,

Your genetic research links to outdated information and has been superseded by more recent research which points to today’s Palestinians being virtually indistinguishable from Israeli Jews genetically. When we take look at,say, the Stanford genetic study, it paints a picture of European Jews with genetic roots of their host nations as well as Middle Eastern, with high admixture of Kurdish markers on the female line.

As to the Canaanites, we now know they form 90% of modern-day Lebanese after last year’s genetic study on what happened to them.

I’m sure you can find the most recent genetic studies with a simple search, but suffice to say that Palestinians by and large can trace their lineage right back to Neolithic times, which a previous study noted, but we’re now talking about most Palestinians and not just some. Also, there’s bound to be some admixture from surrounding regions but it’s not to the extreme that today’s Palestinians came from Arabia – it only shows a slight admixture.

If we’re to state that who should “inherit” Palestine based on genetics, then it seems to be that the Palestinians are several leagues ahead of we Jews on that one and then combine that with the continual presence in the land, well, it only strengthens the claim, but it’s kind of ridiculous since the Palestinians do indeed exist and we are actually occupying their land.

We’d greatly appreciate it if you could provide some links to the various studies to which you allude.