This continues from my previous post on A.J. Woodman’s argument.

History ain’t what it used to be. It is all too easy for us moderns to read a work by an ancient historian, say Josephus or Tacitus or Thucydides (some would even add a few biblical authors), and think that by making allowances for pre-modern naïvety and a few mythical tales that we are reading a regular account of the past not so very different from what we would expect from our own modern historical works.

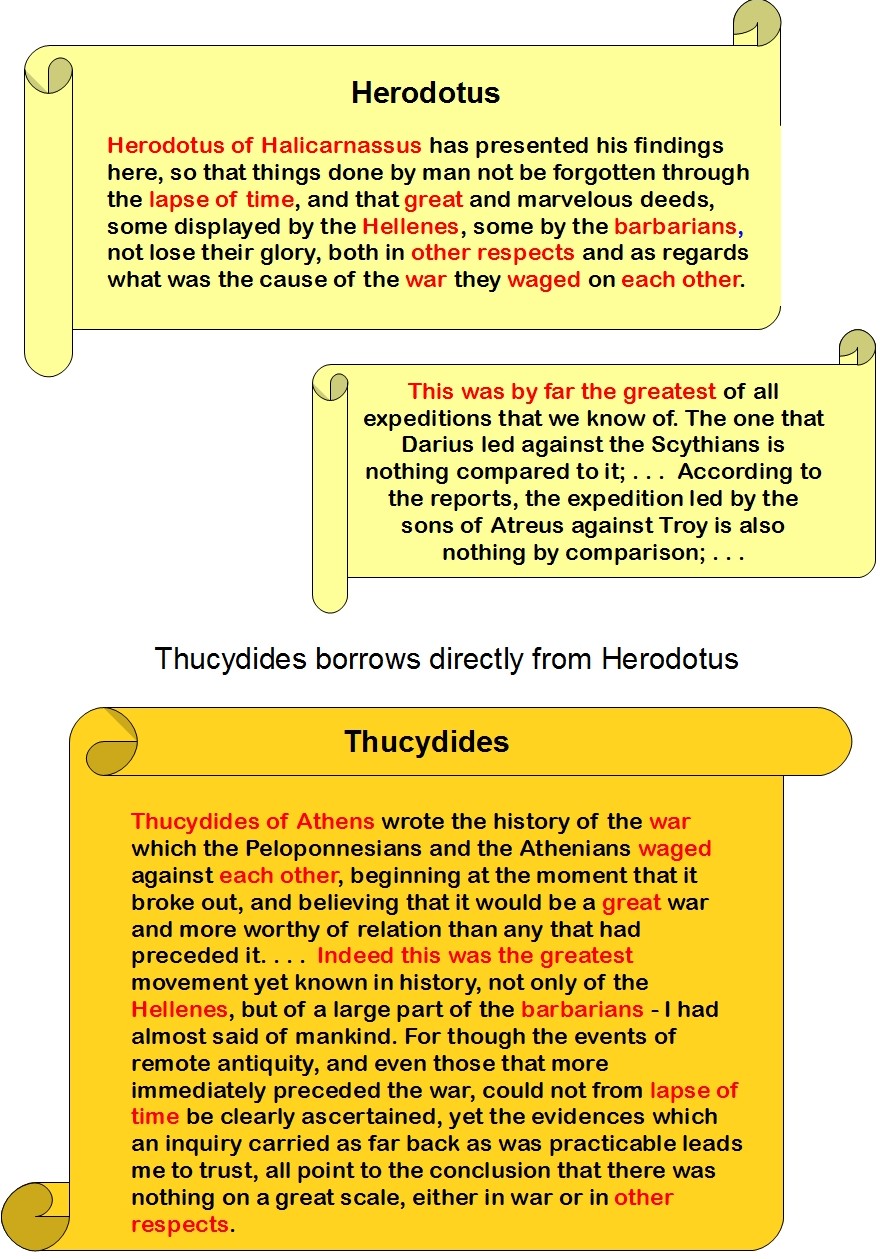

Historical works are nothing like epic poetry. At least to us. Historians are trying to get the facts right and record what they believe really happened. Ancient historians, however, did not quite work like that. We have seen in the previous two posts that even that reputably most “modern” and “scientific” of ancient historians, Thucydides, looked upon Homer as a historian-predecessor of his. If the Iliad is what Thucydides understood as “history” then perhaps we should be a little more cautious in the way we approach his own historical work, and indeed historical works of all the ancients.

How prose trumped poetry

Thucydides rejected poetic presentation. Plain prose was his tool. We saw in the previous post that his rejection of the poetic with all the embellishments that poetry brings with it was not because he believed such a medium was inappropriate for a “historical work”. Rather, it was because he wanted to convince his audience that the subject matter about which he was writing was itself of such grand and superior importance that poetry was superfluous.

The topic or theme was impressive enough on its own merits. In this, the greatness of his subject, his work surpassed that of his predecessors, including Herodotus and Homer.

Thucydides made poetics sound like a cheap way to enhance the greatness of one’s chosen topic.

Below we have a closer look at that prose style and will see that even ancient readers saw something rather poetic about it anyway. Thucydides’ prose was far from pedestrian.

(Pause: Did similar thoughts run through the mind of the author of Luke-Acts? What greater subject to write about than the coming of Christ and the origins of the Church? How to surpass the predecessors?)

Thucydides “the disaster drama” entertainer

In the previous post we saw that Thucydides expressed regret that readers “may seem” to find his work “less entertaining” because it would lack the tales of the fabulous and legendary that were found in The Histories of Herodotus. Woodman’s translation draws attention to what he believes are key details in the Greek that tend to be overlooked by many readers, including scholars. Thucydides, he argues, is not saying that his work will not be found entertaining. He is saying that it will lack the entertainment that comes from the mythical and fabulous narratives since those sorts of stories won’t be a part of his work.

We must infer that he did expect his work to be entertaining in all other respects, which is certainly the impression we derive from 23.1-3, where he returns to the thesis . . . that [his subject matter] the present war is the greatest of all. (p. 28)

Here is 23:1-3

Continue reading “The Best of Ancient Historians Following Homer and the Epic Poets”