.

| Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here. |

.

Brodie is analysing John Meier’s work, A Marginal Jew, as representative of the best that has been produced by notable scholars on the historical Jesus.

Brodie is analysing John Meier’s work, A Marginal Jew, as representative of the best that has been produced by notable scholars on the historical Jesus.

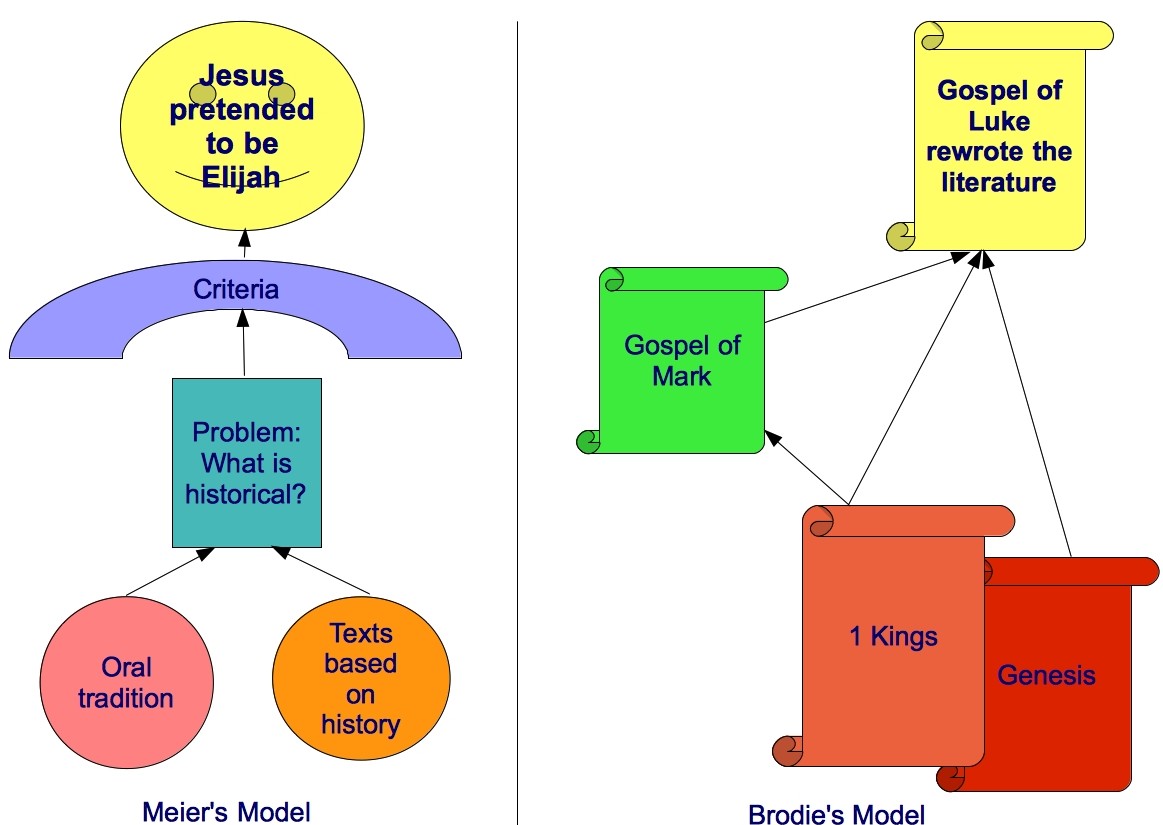

Having begun by identifying the two key problems of Meier’s work as (1) reliance upon the oral tradition model and (2) misreading the sources as windows to historical events as a result of failing to appreciate the true nature of those sources by means of literary analysis, Brodie next showed how these two problems misled scholars into the daunting task of attempting to sift the genuinely historical elements from the Gospel narratives.

That task of divining the historical from the non-historical has led to the development of criteria. But Brodie argues that all of those criteria are flawed in some way (a point few of Brodie’s peers would disagree with; that is why they believe they are on stronger ground if they use several of them, never just one, and use them “judiciously”) but that several of them in particular are best and most simply and directed answered by a deeper and wider understanding of how ancient literary artists worked. Contradictions and discontinuities are a pervasive feature of the literary makeup of the Biblical texts and function in consciously planned ways.

To add another illustrating example from the one I gave from Brodie himself in my previous post, this one not from Brodie but from my own reading of scholarly works comparing Herodotus’ Histories with the Primary History of Israel (Genesis to 2 Kings), a number of scholars have argued that the contradictory accounts of such events as David’s rise to power are set side-by-side just as Herodotus likewise pairs contradictory accounts of certain events in Greek history. The notable difference with the biblical literature is that in the work of Herodotus the author has intruded into the narrative the voice of a narrator to comment on these differences. The Gospels are following the style of the OT “histories” of removing, for most part, the directly intrusive narrator’s voice.

The criterion of multiple attestation also fails since, according to Brodie, the various sources are not at all independent but are re-writings of one another. Re-writing and transforming texts was a singular feature of the literary compositional techniques of the day.

Disastrous consequences

So when some scholars see the clear allusions in the Gospels of Mark and Luke to the stories of Elijah, failing to understand how ancient authors more generally imitated and emulated other writings, they conclude that Jesus himself was deliberately (historically) modeling himself upon Elijah! John Meier, for one, concludes that Jesus historically saw himself as standing in the line of Elijah and Elisha (Marginal Jew, III, 48-54). But as Brodie points out,

To claim that Jesus modeled his life on Elijah or Elisha may be a very welcome idea, but it goes beyond the evidence. It is not reliable history. (p. 158, my bolding)

Jesus’ call of his disciples as a case study

Meier views the call of the disciples as found in Mark, Matthew, and Luke as reflecting an historical event. Reasons? I don’t have volume 3 of Meier but Brodie sums them up thus:

- The call involves a distinctively sharp command, “Follow me”

- And it is backed by texts independent of one another (including Q and L)

As we would expect by now, Brodie challenges the second point (independence of the texts) on the grounds that it rests on a particular theory of textual relationships that hypothesizes the existence of additional texts, Q and L (material unique to Luke).

An alternative theory, more complex, but more solidly grounded, shows that these texts depend on one another . . . and once the links are traced, the independence disappears. (p. 158)

What of the first point, the “distinctively authoritative command”?

It not only reflects Elijah’s authoritative call of Elisha (1 Kgs 19.19-21; cf. Marginal Jew: III, 48); it is also a variation on the command-and-compliance pattern at the beginning of the Elijah account (1 Kgs 17.1-16). ‘This “command and compliance” pattern is common not only in the Elijah stories but elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible as well’ (Walsh 1996: 228).

In fact, it adapts the pattern of command-and-compliance that occurs both at creation (Gen. 1) and in the call of Abraham (Gen. 12:1-5; cf. Brodie 2000: 31-46).

So, Jesus style of calling disciples, his calm authoritative command, is patterned as a continuation of God’s way of creating the world. What the Gospels show is continuity in the portrayals of the Creator, Elijah and Jesus. The conclusion that accounts for the data is literacy: the portrait of Jesus is modelled ultimately on that of the Creator. To claim an individual history behind the text goes beyond the data. (p. 158, my formatting and bolding)

I first read of the pattern of creation being repeated like a unifying thread across the narratives throughout the Bible in Thomas L. Thompson’s, The Mythic Past. His reference was to the dividing of the waters to symbolize the emergence of a new creation, a refrain found in Genesis 1, the Flood, the Exodus, the Crossing of the Jordan, Elijah’s and then Elisha’s crossing of the brook, the baptism of Jesus (the waters have been superseded here by the dividing of the heavens!)

Brodie turns Meier’s own words against his own interpretation of the evidence:

Elsewhere, Meier expresses the principle (Marginal Jew: 1, 67):

A basic rule of method is that, all things being equal, the simplest explanation that also covers the largest amount of data is to be preferred.

In this instance, the simplest explanation that accounts for the data is that the evangelists adapted the biblical figure of Elijah to draw the picture of Jesus. (p. 158)

Surely there are other major hurdles to the notion that Jesus consciously modelled himself on biblical figures. Maybe others have studied the ins and outs of this argument more than I have and can explain away some of my objections. As it stands, surely any effort by someone to model himself on another person requires the support of others. The image of the call in Mark and Matthew is that of a miracle, of a supernatural event. It makes absolutely no sense as historical reality. Were the disciples so easily hypnotized that they simply dropped their livelihoods at a laconic command from a passing stranger? But the image makes every sense as, Brodie points out, an image of a divine command wielding power to create a new beginning.

And as for Luke’s version of the call, we can see that there the author is deliberately revising Mark’s account to support his own ideological agenda. I also recently showed how historical interpretations actually destroy the meaning of the Gospels. (This theme I have taken also from Thomas L. Thompson who demonstrated (again in The Mythic Past) the way attempts to remove the miraculous elements from the Bible’s stories do not bring us any closer to historical reality, but only succeed in destroying the point of the stories.)

Some scholars seriously suggest that Jesus was likewise modelling himself upon his biblical forebears at his entry into Jerusalem. Such an accomplishment would, of course, have required the payment of large numbers to come out and act their part as the welcoming committee. And why did the evangelists get confused about which person Jesus was supposedly deliberately imitating? Mark implies it was Elisha while John was imitating Elijah, Matthew implies it was Moses, and Luke Elijah only. Does it not make more sense to think each evangelist creates his own meaning for Jesus through a different hero?

And if Jesus was truly imitating the prophets or kings, why on earth did he allow himself to be called “Jesus of A-Town-Nobody-Has-Ever-Heard-Of”? Why not “Jesus Son of David” or “Jesus The Prophet-To-Come”? (Of course, I am referring additionally here to the fallacy of interpreting “Jesus of Nazareth” as having originated as a geographical reference in the first place.)

The objections to the view that the OT allusions in Jesus’ life are to be explained as attempts to Jesus to model himself upon biblical characters are monumental. They border on the ludicrous.

I am well aware that historical persons, ancient and modern, do deliberately create public images to associate themselves with historical or mythical persons. Emperor Hadrian promoted himself as Hercules. Alexander as Dionysus. Modern political leaders echo refrains from national heroes. But what we see across the different Gospels are the different attempts by the respective authors to create a Jesus according to their own thematic interests. For Matthew Jesus was a new Moses (see Dale Allison’s The New Moses) for Luke he was the new Elijah and we can see Luke taking pains to remove all of Mark’s Elijah associations from John the Baptist. We have direct evidence that Hadrian, Alexander, and modern political leaders have modelled themselves on other figures — coin images, accounts of dress, political propaganda and speeches — but we only have narrative frameworks to associate Jesus with a range of sometimes contradictory figures. And those analogous characters are most simply explained as ciphers for how each author wants us to interpret Jesus theologically.

Scholars truly have badly stumbled when they fail to recognize the literary origins of the way Jesus is related to characters in other texts. Even laypersons can see how badly they have done so.

Bart Ehrman complains that some laypersons “seem – to a person – to have endless time and boundless energy to argue point after point after point after point after point.” That’s a very strange admission to make. What he is unwittingly conceding here is that many laypersons really have read his books, studied some of the topics deeply, engaged with the scholarship, a lot more than he wants to admit. They really do know that the standard catechisms of historical Jesus arguments have many logical and evidential flaws. And what’s worse, they have not been “trained” in the seminaries so they have been exposed to critical questions that the establishment has always brushed aside and that challenge the very foundations of historical Jesus studies. Such are the woes for scholars that the internet has ushered in.

Response? Don’t give those intellectual lepers any credibility by even engaging with them. Respond with a few tired old mantras, keep the details behind a pay-wall if one prefers, and insult those who seem to know too much for their own good and will no longer accept the Establishment interpretations. If they don’t accept the interpretations of the scholars and insist on challenging the scholarly assumptions and questioning logical flaws, then accuse them of being “untrained” and therefore “unqualified” and “arrogant” for refusing to stop questioning the evidence and logic of the Masters. How else can such scholars defend themselves from an increasingly informed lay public?

As for the few scholarly peers who fall by the wayside, pity them, and suggest they have psychological problems because of their past religious mistakes, or, like the elder John, suggest they were never “truly among us” academically minded folk in the first place.

A quaint little aside:

Serious grown men (scholars, even) in modern USA are currently exerting time and energy in attempting to find models that reconcile human evolution with the Bible account of Adam and Eve. Publications about Homo divinus indeed! Meanwhile, a larger number of scholars are endeavouring to reinterpret and revise the meanings of the Gospel evidence to make it fit with their assumption of an historical Jesus.

I do believe the “mythicists” — both Adam and Eve as well as Jesus mythicists — demonstrate a greater respect for the evidence of the Biblical texts and for the fundamental rules of scientific and historical methodologies than most Biblical scholars seem to do.

.

Next: Was Jesus a Carpenter?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I have read and re-read the book-memory of T. Brodie, but the Neil’s posts allow me to see interesting details of the book that I had missed or that I had overlooked, prima facie.

Very Thanks to Vridar, for this.

Giuseppe