|

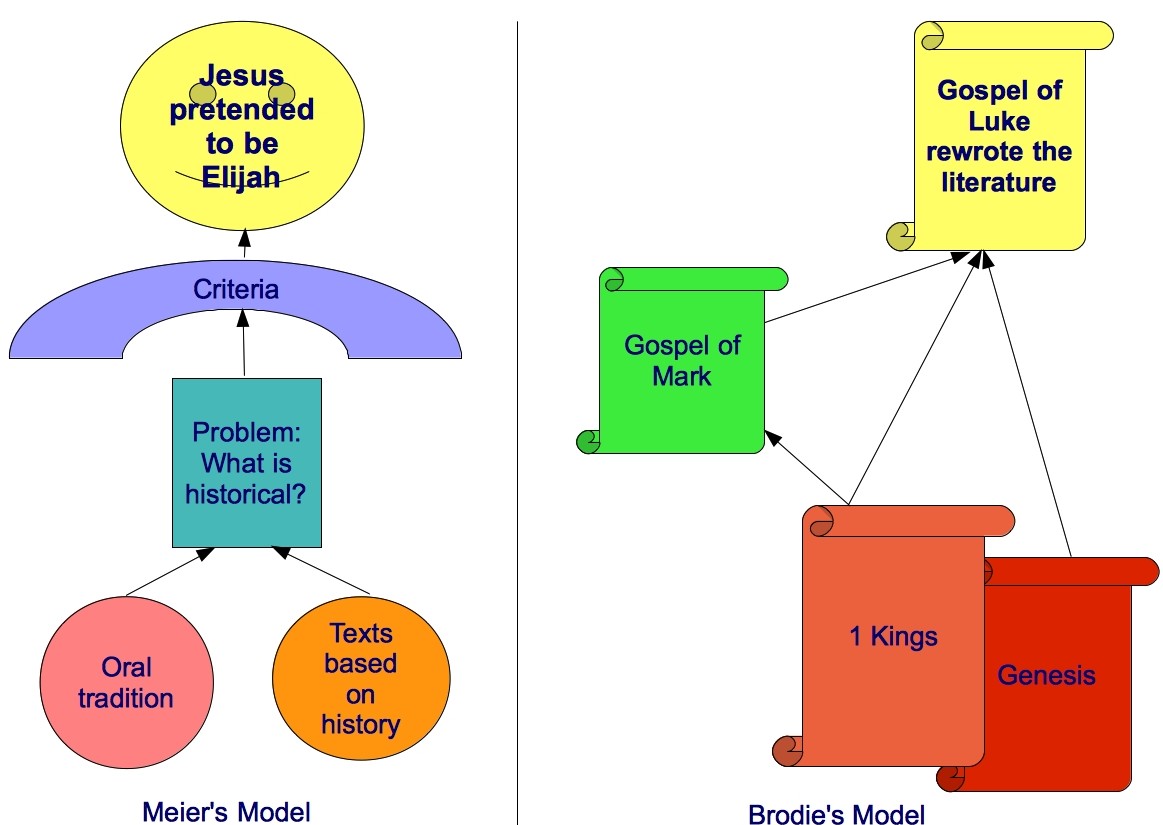

Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here. In chapter 17 Brodie is analysing John Meier’s work, A Marginal Jew, as representative of the best that has been produced by notable scholars on the historical Jesus.

|

We saw from the opening post on Brodie’s seventeenth chapter that John Meier rests his case for the historicity of Jesus on the evidence of Josephus. Josephus is an independent witness to the existence of the Jesus of the Gospels and therefore is decisive, or in Meier’s words, “of monumental importance.”

We saw from the opening post on Brodie’s seventeenth chapter that John Meier rests his case for the historicity of Jesus on the evidence of Josephus. Josephus is an independent witness to the existence of the Jesus of the Gospels and therefore is decisive, or in Meier’s words, “of monumental importance.”

Brodie, “with a prayer to heaven, along with many saints and scholars, and also to Agatha Christie, Hercule Poirot, Sherlock Holmes, and Watson”, undertakes to examine how Meier came to this critical conclusion about the nature and significance of the evidence of Josephus.

Brodie sees two problems with the references to Jesus in Josephus:

- Authenticity: Do they really come from Josephus or from some later Christian writer/s?

- Independence: Even if the references are authentic, are they truly independent witnesses, of did Josephus get his information from other Christians or the Gospels?

The Question of Authenticity

Bypassing the Jesus reference in The Jewish War as spurious according to virtually all scholars, Brodie zeroes in on Meier’s case for the evidence in Antiquities of the Jews.

In Book 20, in a passage about a certain James, there is a passing reference to Jesus in order to identify this James: James was “the brother of Jesus who was called Christ”. Meier reasons that this passage appears to be referring to a Jesus mentioned earlier. It is very likely, then, that Josephus had earlier written about this Jesus.

And there is an earlier passage, in Book 18, known as the Testimonium Flavianum (the “Witness of Flavius (Josephus)”) that

- summarizes the work and character of Jesus

- tells us that Jesus was accused and crucified under Pilate

- says Jesus still in Josephus’s own day maintained a following, the Christians

and in the course of that summary, the same passage says

- Jesus should perhaps be thought of as more than a man

- that Jesus was the Christ

- that Jesus appeared to his followers alive again three days after his crucifixion as the prophets had foretold.

Some scholars still see the entirety of this passage as a total interpolation. But given the implication of the passing reference in Book 20, Meier believes it cannot be a complete forgery. Josephus must have said something about Jesus here.

We have, then, three possibilities to explain this passage:

- It is entirely original to Josephus

- It is entirely an insertion by a Christian hand

- It is a mixture of original and insertion.

Meier excludes the first two options:

- It cannot be entirely by Josephus because it proclaims Jesus as the Christ

- It cannot be entirely inserted because Book 20 implies something was said earlier about Jesus

Therefore #3 is Meier’s conclusion. Josephus said something, but he would not have said Jesus was more than a man, that he was the Christ, or that he rose from the dead.

That is, omit the phrases that Josephus would not say and, presto, we are left with what Josephus would have said! And with these omissions “the flow of the thought is clear”, Meier adds.

Brodie is happy to provisionally accept Meier’s conclusion as “a reasonable working hypothesis”. So he moves on to the next question.

Thus Brodie presents Meier’s case for authenticity positively (if somewhat provisionally). In this Brodie argues a case that is unlike that of any other mythicist argument that I know of concerning the Testimonium. So his argument should be of special interest. Continue reading “Making of a Mythicist — ch 17 . . . The Evidence of Josephus”