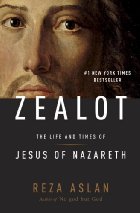

Reza Aslan’s book about Jesus, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, opens its prologue like an historical novel:

Reza Aslan’s book about Jesus, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, opens its prologue like an historical novel:

The war with Rome begins not with a clang of swords but with the lick of a dagger drawn from an assassin’s cloak. (p. 3)

Addressing the reader in the second person Aslan draws her into the colourful world Jewish worship at the Jerusalem temple and shocks her after half a dozen pages by having her witness the assassination of the high priest there in 56 C.E. One knows one is in for a dramatic read.

For the more academically minded reader there are over fifty pages of endnotes detailing sources and additional explanations for what appears in the main text. To Aslan’s credit, he makes abundantly clear in his introductory “Author’s note” that

For every well-attested, heavily researched, and eminently authoritative argument made about Jesus, there is an equally well-attested, equally researched, and equally authoritative argument opposing it. (p. xx)

That’s a refreshing change from the way some scholars introduce their own work or criticize the works of others. Aslan explains that his footnotes attempt to present some of the arguments of those who oppose his views in the body of the book.

Why this book about Jesus?

By way of preliminaries, however, Reza Aslan recounts how, after migrating from Iran, he became a Christian at fifteen years of age and how this new identity happily served to strengthen his identify as an American.

In the America of the 1980s, being a Muslim was like being from Mars. My [Muslim] faith was a bruise, the most obvious symbol of my otherness; it needed to be concealed.

Jesus, on the other hand, was America. He was the central figure in America’s national drama. Accepting him into my heart was as close as I could get to feeling truly American. (p. xviii)

Not that his conversion was a matter of convenience,

On the contrary, I burned with absolute devotion to my newfound faith. I was presented with a Jesus . . . with whom I could have a deep and personal relationship.

Not “convenience” perhaps, but Reza might as well have added that he converted to the American way of devotion to the American religion.

And again like (most?) well educated Americans Aslan lost his naive fundamentalist beliefs as he learned more about the Bible, while at the same time becoming

aware of a more meaningful truth in the text, a truth intentionally detached from the exigencies of history. (p. xix)

Not being an American I was unaware of Reza Aslan’s prominent public profile as a Muslim scholar. If I had never seen the Fox interview with Aslan about this book but relied upon the book alone I would have assumed Aslan had left the Muslim religion and was writing as a liberal Christian (American and still evangelizing) scholar. He writes: Continue reading “Introducing Reza Aslan’s Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth“