The theme of Act 2 is how Brodie learned that the biblical writers found much of their material in literary sources.

The theme of Act 2 is how Brodie learned that the biblical writers found much of their material in literary sources.

In 1980 Brodie met Joseph Fitzmyer in Washington, DC, and asked him to comment on an article he (Brodie) had had published in the Journal for the Study of the New Testament the previous year. It was on Luke’s use of Chronicles. After considering the argument Fitzmyer set Brodie on a new journey with one question:

‘Is the process you are invoking found elsewhere in the ancient world?’

Brodie had no answer.

So this is what followed:

As never before I started wading through libraries, and eventually hit on the obvious — the pervasive practice of Greco-Roman literary imitation (mimēsis) and its sundry ancient cousins, many of them Jewish. Jewish practices included rewriting and transforming older texts; and Jewish terms included rewritten Bible, inner-biblical exegesis, and the processes known rather loosely as midrash, Hebrew for searching — in this case searching for meaning.

What I had noticed within the Bible was the tip of the iceberg. Here was a whole world of diverse ways of deliberately reshaping diverse sources.

The process I was invoking was not just present in the ancient word — it was at the very centre of ancient compositions. And the New Testament use of the Old, pivotal though it is, is just part of the larger pattern whereby the Bible as a whole distils the larger world of ancient writing. (Beyond, p. 44 – my bolding and formatting)

Biblical studies, Brodie reflects, “had developed in a world where the very concept of any form of imitation was fading, and aversion to the notion of imitation had affected even classical studies.” Though he had studied both Virgil and Homer in high school there was no teaching that one had imitated the other. The Oxford Classical Dictionary had no entry for imitation until its 1996 (third) edition.

Traditional source criticism

Biblical scholars had long used source criticism as one of their fundamental tools. But this traditional method had not managed to maintain a good name. What it essentially involved was taking one text, say the Gospel of John, and on the basis of that one text alone attempt to reconstruct a hypothetical source that no-one had ever seen or heard of elsewhere.

By means of this method, the favourite source for the Gospel of John was the Signs Source. But this document, the Signs Source, was given such a wide diversity of shapes. John’s chapter 9 account of the man born blind was allocated

- 34 verses in the SS by Becker

- 28 verses in the SS by Bultmann

- 3 verses in the SS by Schnackenburg

- 2 1/2 verses in the SS by Boismard

Clearly the method of determining the shape of this hypothetical source was broken.

The “revolution” of the new source criticism

Brodie’s first revolution in understanding (Act 1) was when he became aware that biblical narratives are not necessarily reliable accounts of history.

His second revolution was a new method of source criticism. Unlike the traditional approach, this new method compared two known texts in order to see if one had used the other as its source.

This method had been used to a quite limited extent in biblical studies before, but what was new was

the quantity of the biblical text that was so indebted, plus the complexity of the ways in which the source texts had been used.

This new source criticism could also offer the prospect of verifiability. That promised genuine progress in identifying sources.

“It needed patience, patience, patience.“

Brodie puts his finger on what I think has been the major bulwark against the wider reception of his thesis. To explore the possibility of sources this way required “patience, patience, patience”, and Brodie explains what he means. It is not the same as endurance:

Patience means being receptive to something different, even strange, something that goes against one’s established picture, that challenges the imagination. (Beyond, p. 45)

Radical implications

The Synoptic Problem — the study of the literary interrelationships among the first three gospels — is essentially a question of sources. The search for the sources of these gospels has been intense, but as Brodie points out, that search

made little reference to the complexity of how the rest of the world used sources.

The study of the sources for the Gospel of John likewise made little reference to the ways authors used sources in the wider world.

Brodie compares his dawning understanding of how the ancient literary culture made use of sources, and how the biblical authors fitted into this culture, with a sailor’s discovery of a new continent and how it slowly emerges from the horizon.

Getting that thesis done

Throughout 1981 Thomas Brodie taught at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, while he completed his dissertation under the direction of his Rome-based supervisor who was living there at the time.

Its title: Luke the Literary Interpreter: Luke-Acts as a Systematic Rewriting and Updating of the Elijah-Elisha Narrative in 1 and 2 Kings.

Eventually Brodie handed his supervisor what he thought was his thesis — “350 pages magnificently and expensively typed.”

A week later he called me in. ‘That will do fine”, he said, “as an initial, preliminary, opening first draft. You will re-write it according to the following specifications.” And he spelled out a methodical sequence for analyzing and presenting the material. (Beyond, p. 46)

Brodie did, and produced a clearer and more convincing work as a result. At the end of the year, December 1981, his thesis was accepted in Rome.

Research fellowship @ New Haven

With a recommendation from Brevard Childs Brodie had meanwhile taken up a research fellowship in New Haven, Connecticut, at Yale Divinity School. This was August 1981.

With a recommendation from Brevard Childs Brodie had meanwhile taken up a research fellowship in New Haven, Connecticut, at Yale Divinity School. This was August 1981.

There he attended a seminar led by Luke Timothy Johnson, “Method and Madness”. The methods used in New Testament research were analyzed.

His critiques were thorough and devastating. Here was a man who could think. Ultimately I was disappointed. I felt that at the crucial moment, when the time came to synthesize the conclusions of all his critiques, the seminar flinched. Maybe it seemed there was no alternative. (Beyond, p. 47)

Yup. Know the experience well. Brodie was encouraged the way the seminar clearly spelled out his own “half-formulated concerns”.

Brodie also profited from Abraham Malherbe‘s seminar on history (Luke and Greco-Roman background), and was given the opportunity to present to the class his own evidence that part of the Stephen story in Acts 6-7 was sourced systematically from the story of the false accusing and stoning of Naboth in 1 Kings 21.

Malherbe was genial enough but deflated Brodie’s ego when he said with a smile,

Malherbe was genial enough but deflated Brodie’s ego when he said with a smile,

I hope, Tom, that you don’t think you convinced me.

Brodie realized he still had a lot to learn in order to present the evidence in a “sufficiently clear and strong” way. Discussing the problem with Luke Johnson, Johnson advised Brodie to keep working on clarifying the content and presentation and to submit it for publication to the Catholic Biblical Quarterly.

Struggling with the Gospel of John

For most of the 1982-1983 year Brodie turned from the Synoptics to try to understand the Gospel of John’s sources. He focused on John 9, the account of the man born blind. Back in the 1970s he had already linked this chapter to the Namaan narrative in 2 Kings 5, but now he was seeing the Synoptic gospels (in particular Mark 8.11-9.8) as more immediate and substantial sources.

The evidence favouring John’s dependence seemed overwhelming — dozens of links, many of them substantial; but there was no clear pattern, and so the evidence as a whole was not convincing. I realized I was trying to explain how John 9 used sources without knowing John’s meaning. . . . (Beyond, p. 47)

The study of that chapter’s meaning necessitated a study of the meaning of the rest of the Gospel. It was a long road to travel.

Reward: A toehold

The experience of completing the dissertation and the time spent at New Haven taught Brodie (“for the first time in my life”) how to present a proposal and set out an argument according to the proper academic manner, adding the necessary qualifications and providing adequate supporting documentation.

(Apparently James McGrath in his review did not manage to read as far as the sixth chapter of the book and that’s why he claimed Brodie never learned to do scholarship; we do know that he has felt qualified to write reviews of books by mythicists after skimming no more than the first few pages.)

Attending conferences enabled Brodie to meet other researchers and share valuable lessons.

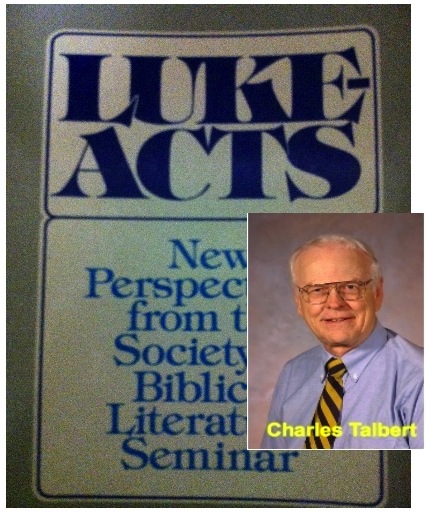

One person who heard him deliver a presentation at one of those conferences was Charles H. Talbert. Talbert invited Brodie to contribute a chapter to a book he was preparing, Luke-Acts: New Perspectives from the Society of Biblical Literature that appeared in 1984.

One person who heard him deliver a presentation at one of those conferences was Charles H. Talbert. Talbert invited Brodie to contribute a chapter to a book he was preparing, Luke-Acts: New Perspectives from the Society of Biblical Literature that appeared in 1984.

(You can still buy a new copy of this online for over $400 or a second-hand copy for about $12. Brodie’s article, “Greco-Roman Imitation Of Texts As A Partial Guide To Luke’s Use Of Sources”, is the second chapter of the book.)

Two other articles were published in 1983: one in Biblica and the other in CBQ (the Stephen-Naboth article).

[N]ine years after finishing the basic manuscript in Normandy, I had recovered energy and had gained a toehold in the academic world. The former editor of the CBQ — the person who told me to try another journal — offered a quiet but genuine word of appreciation. (Beyond, p. 49)

Again through the recommendation of Brevard Childs, Brodie was invited by Wilfrid Cantwell Smith, director of Harvard’s Center for the Study of World Religions, to join twelve others at a two-month post-graduate summer Seminar to explore a new modern concept of scripture. Brodie particularly wanted Smith’s feedback:

I asked him would he be interested in a manuscript, and he responded positively.

Within a short time he returned it to me.

‘That is an important thesis.‘

He wanted it published.

I told him about some publishers’ doubts, but he still thought it would be good to try again, and, on his suggestion, I sent it to Beacon Press, Boston. (Beyond, p. 50)

You guessed it. Beacon Press eventually rejected it, too.

Related articles

These posts also look at the Gospel of Luke’s relationship with Chronicles

- ‘Is This Not the Carpenter?’ Reviewing chapter 11, Luke’s Sophisticated Re-Use of OT Scriptures (vridar.org)

- ‘Is This Not the Carpenter?’ review (chapter 11 continued) (vridar.org)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

It’s reassuring that major figures like Childs, Talbert, and Wilfrid Cantwell Smith all recognized the importance of Brodie’s thesis and encouraged him. Not all Biblical scholars are brainwashed drones mindlessly repeating the orthodox script.

“The Oxford Classical Dictionary had no entry for imitation until its 1996 (third) edition.”

That was unsettling to read. You’ve pointed out many times how far behind classical scholarship Biblical studies are, but in this case it appears they’re about even. I’m stunned to learn that mimesis is such a new theory, even in classics.

I need to make one qualification here.

Yes, I find it bizarre (to be polite) that Jimmy McG could possibly write the “review” he did. He was, by implication, insulting the integrity and professionalism, even the intelligence, of the likes of Charles H. Talbert and Wilfrid Cantrell Smith.

Again, I do not believe McGrath even read the book in its entirety. Surely he merely skimmed it. That would explain why he speaks of his “impression” on the basis of snippets of data that are found in “the same section” of the book. His claim that Brodie is some sort of parallelomaniac who even resorts to finding evidence of borrowing in common prepositions is irresponsible, unprofessional, — an outright lay (is that how one spells the word for peddling false information?) If McG ever read chapter 7 of Brodie’s book then his falsehoods are without excuse. (But I’m told I should restrain my language and play the game so no-one in academia gets upset and the apologetic status quo continues as it has for the last however many generations.)

Back to my one qualification.

Yes, Brevard Childs did commend Brodie for the research fellowship and to Wilfrid Cantrell Smith, but Childs himself did not specifically address Brodie’s thesis of Gospel-OT mimesis. Brodie at one time did intend to raise his thesis with Childs but after a cordial conversation lost his courage and failed to do so. He could never quite get a handle on where Childs might stand with regard to the challenge it presented.

Neil, this really is a tour-de-force! Your excellent description of Thomas Brody’s long and difficult road to “learning how to do scholarship” (in McGrath’s words) *before* he earned his doctorate makes me want to buy, beg, borrow or steal the book at the earliest possible opportunity — my budget doesn’t allow purchasing of books :^( — and see for myself how Brodie became a serious scholar and an MJer instead of an HJer. Thanks!