Edited with additional notes on compatibility with other models of gospel origins 3 hours after the original posting.

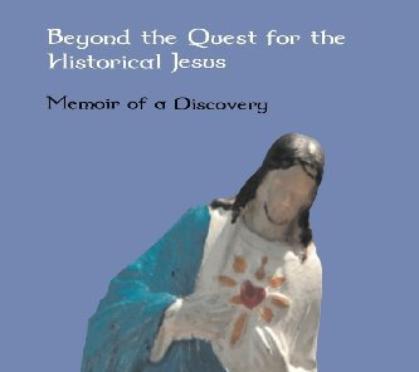

- The Making of a Mythicist, Act 1, Scene 1 (Thomas Brodie’s Odyssey)

- Making of a Mythicist, Act 1, Scene 2

- Making of a Mythicist, Act 2, Scene 1 (Brodie’s Odyssey)

Continuing . . .

Brodie is discovering where the New Testament writers found their source material. This is the pattern of literary dependence that he was beginning to see (elaborated with details from Birthing of the New Testament):

|

I like the idea of a pre- or proto-Matthean collection of sayings. The earliest “Fathers” seem to make a lot of use of such a compilation with apparently little or no knowledge of a fuller Gospel of Matthew. (But of course I also like to date the Gospels to the second century, with Mark’s imagery linked more pointedly to the Second Jewish War — Bar Kochba and Hadrian — than the first.)

I’d also like to study Brodie’s idea of Proto-Luke to see if it is compatible with Joseph Tyson’s understanding of an Original Luke.

And I’m especially happy to see Brodie also places canonical Luke-Acts AFTER John! That really does have so much going for it — ever since another “mythicist”, Paul-Louis Couchoud, broached the idea. But also see Shellard, Matson, Lawrence Wills, and others.

Such a sequence pointed to a complex literary and historical process, provided a framework for approaching the NT writings, outlined a solution for the Synoptic Problem, and a context for discussing John.

But was it correct?

After 48 hours in an overcrowded Beirut prison on suspicion of being a spy for Israel (in the wake of an Israeli raid on Lebanon) Brodie returned to Normandy.

There, for what eventually became two and a half years, I scrutinized the primary texts more closely, elaborating all the time, trying to some degree to articulate the criteria for establishing literary dependence, and constantly testing, testing, testing. (Beyond, p. 34)

We have seen that McGrath tells his readers that Brodie indicates the reason his work was rejected by publishers was that it lacked things like proper footnotes and poor grammar, along with some presumably perverse attempt to insist on a “Christian” publisher. He also makes the delinquent claim that Brodie appears never to have questioned his thesis or sought any genuine criticism of it — an assertion that will be shown to be blatantly false through this and other posts.

Here is Brodie’s version of his initial attempt to have the above outline published:

In Spring of 1975 I produced a manuscript and immediately showed it to a British publisher, and then to a second, but their responses indicated that it was not at all what publishers wanted. What ruled it out above all else was its conclusion that Jesus had not existed. As the first publisher said, ‘It’s not just that we won’t take it. Nobody will take it.’ The second publisher said no Christian publishing house would take it. (Beyond, p. 35)

Brodie later explains (p. 36) that he was approaching editors of “biblical journals” and publishers of such scholarly works.

Brodie comments on these initial rejections (again with my emphases):

And yet the evidence was very strong. In testing the Gospels, essentially every strand concerning the life of Jesus consistently yielded clear signs of being dependent on older writings — on the epistles, and on the Old Testament, especially in its Greek version. The clincher was 1 Corinthians. I knew I had not analyzed its sources fully, but the evidence was sufficient and consistent — especially regarding its use of the Pentateuch, particularly Numbers and Deuteronomy — to know that its picture of Jesus was essentially a synthesis and adaptation of older Jewish traditions. Even Paul’s list of possible resurrection appearances (1 Cor. 15.5-9) turned out to be largely a synthesis and adaptation of the diverse descents and appearances of the Lord during the crises of Numbers 11-17 (note esp. Num 11.25; 12:5; 14:10; 16:19; 17.7). (Beyond, p. 35)

So Brodie turned to old friends in Trinidad who were well trained in the scriptures to go over his manuscript again and see if it should be scrapped or not.

That’s where Brodie’s evening conversation with Everard Johnston comes in. I quoted it as the introduction to my recent post, Brodie’s Argument That Jesus Never Existed. The conclusion:

Suddenly he said, ‘So we’re back to Bultmann. We know nothing about Jesus.’

I paused a moment.

‘It’s worse than that’.

There was a silence.

Then he said, ‘He never existed’.

I nodded.

There was another silence, a long one, and then he nodded gently, ‘It makes sense’.

This, of course, is indeed the natural conclusion to be drawn from Brodie’s analysis of Gospel (and epistolic) sources. If the writers were drawing from earlier literature their writings about Jesus then, of course, we are no longer left with any reason to believe that their understanding was handed down via eyewitnesses and oral tradition. The only Jesus we can know is a literary Jesus, and if that literary Jesus is drawn from other literary sources quite independent of Jesus (rather than from oral tradition), then . . . . .

Brodie tells us another anecdote, one that is less dramatic and somewhat comical. One of his parishioners had gathered there was something he was not saying, and when she pushed him, Brodie was quite worried about what his confession would do to her faith. But she only laughed it off saying that she had never believed Jesus really existed!

Turning to the Dominicans: Rome, Paris

Unfortunately, Brodie’s friends were too busy with their own affairs to give his manuscript the attention it needed.

The answer?

The Dominicans! Rome!

So Brodie dashed off from Trinidad to Rome to meet with the Magister Generalis with the following in mind:

If I could get a group of Dominican biblical scholars to examine the manuscript they would be able either to demolish it or to issue a calm and confident statement about its value and implications. And it seemed that the one person who might gather such a group was the head man. (Beyond, p. 36)

I quoted part of Brodie’s conversation with “the head man” (Vincent de Couesnongle) in Joel Watts Acclaims Thomas Brodie a Scholarly “Giant” and His Work “A Masterpiece”:

He listened to me patiently, and looked carefully through some of the manuscript. I brought the conclusions to his attention.

‘You cannot teach that’, he said quietly.

I explained that I didn’t want to teach the conclusions, just the method, as applied to limited areas of the New Testament. If the method was unable to stand the pressure of academic challenge, from students and other teachers, then I could quietly wave it good-bye and let the groundless conclusions evaporate in silence.

It was a Saturday afternoon. He needed time to think it over. He would see me in a few days. (Beyond, p. 36)

The Master General denied Brodie’s request. He could not call up busy people to examine “un truc“.

Brodie approached journal editors and

- One had a two-year waiting list that could not be broken for anyone;

- The next said the manuscript material was beyond his competence;

- The third said he was interested and took an excerpt to read overnight.

Brodie called back to see #3. He was out. But he had left a message:

I am not interested in this or in anything of a similar nature.

So back to Normandy it was. On his way he stopped by the Dominicans in Paris. He had written a minor thesis on Yves Congar so chose to approach him for feedback:

He glanced at the manuscript and then looked at me rather sadly, ‘I have neither the time nor the competence‘.

To print or not to print?

Brodie was prepared to pay a printer £3,000 to produce a book from his manuscript —

so that it would have a chance either to make a contribution or to be roundly rebutted. (Beyond, p. 37)

Is not this what most serious “mythicists” (Price, Doherty, Wells, Ellegard, . . . ) want? A genuine critique and engagement with their arguments? The same old avoidance has been there from the beginning. Instructively, even one of the internet’s most hostile of anti-mythicists has acknowledged the strength of Brodie’s methods and arguments — but only after reading them whilst unaware of the logical conclusions to be drawn from them. Note that Brodie was making a habit of drawing the conclusions of his methods to the attention of those he wanted most to provide critical feedback. (As I also recently pointed out, it is quite amusing and sad to see other scholars who advance the same types of methodology consistently making something akin to a faith declaration along with their arguments: “Don’t ‘misunderstand’ (meaning, ‘Don’t understand the obvious’), I still believe Jesus was historical!”)

Brodie allowed his friend Damian Byrne to talk him into cancelling the costly printing of his manuscript, a decision he later regretted.

This was the late 1970s.

The Documentary Hypothesis — the view that the Pentateuch was based on four sources — was in trouble. The traditional historical-critical-methods were being questioned. At the annual meeting of the Catholic Biblical Association (Detroit) Brodie even raised the possibility that part of the Pentateuch was a response to the writings of the Prophets. Later that same year (1978), after formally joining the CBA and SBL, Brodie wrote up this thesis as a Research Report for the CBA. This was actually an application of the same methods he had used for discerning NT indebtedness on the OT, but here he was using them to argue that part of the Pentateuch was sourced from the Prophets.

It is at this point that Brodie relates the reason he late in becoming proficient in the use of footnotes and bibliographies, and how this gap in his training made his efforts at writing “tortuous”. It is also at this point that Brodie sought critical comments from the renowned scholar, Raymond F. Brown, who responded to one of his articles to be submitted to the Catholic Biblical Quarterly with:

You need to tighten the grammar. . . It has a chance.

Unable to have his articles accepted by the CBQ he asked its editor for advice. He said,

Try another journal.

I include this sort of detail here as a response to McGrath’s distortions of Brodie’s explanations.

Geza Vermes delivers his verdict

Meanwhile Brodie’s friend, Damian Byrne, had submitted his manuscript to “scholars with international reputations”. Or so Brodie understood. Later he wondered if it had been, rather, shown to just one scholar — Geza Vermes.

As an Oxford-based eminent Jewish scholar who had become a Catholic priest and later returned to the Jewish faith, Vermes had huge standing. He had worked on the rewriting of Scripture and I could see how he might have seemed to be a good referee. The only details I remember from Vermes’ statement, apart from his negative assessment, was that, given his personal history, his judgment was not due to any faith-based prejudice, and that I was not accurate in my comments on the Pharisees.

At the time the scholarly assessment seemed an important event, decisive. It meant that the best international opinion judged the thesis to be untrue. (Beyond, p. 42)

Brodie knew he needed “the discipline of producing an extensive piece of work that, in addition to being well-argued, would be well-documented and well-presented.” That is, he needed a doctorate. He had done the necessary courses preparatory to it. So to that goal he turned his focus.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Excellent writing! It really has the drama of a play. I can’t wait for the next installment.

You really will have to buy the book. I omitted so much, even most, of the real (personal) drama! 🙂

Geza Vermes refers to Brodie’s “comments on the Pharisees.” Do we know what those were? Working back from page 42 of the book where Brodie comments Vermes, I cannot quickly find a discussion of the Pharisees. Thanks.