Anyone interested in learning how terrorists, in particular suicide terrorists and jihadis, think, will find a wealth of interviews with terrorists themselves, their families and friends, as well as studies of courtroom interrogations and police records, in anthropologist Scot Atran’s Talking to the Enemy. (Sam Harris has scoffed at Atran’s views, dismissing them as lunacy. Are terrorist really driven by a desire to enter Paradise? Do they really take up murder simply because they are the most sincere and devout of Muslims and simply because believe jihad is commanded by Allah? Does Atran really blame male bonding in soccer matches for terrorism! Perhaps this post will help shed a little light on where Atran is coming from.)

Anyone interested in learning how terrorists, in particular suicide terrorists and jihadis, think, will find a wealth of interviews with terrorists themselves, their families and friends, as well as studies of courtroom interrogations and police records, in anthropologist Scot Atran’s Talking to the Enemy. (Sam Harris has scoffed at Atran’s views, dismissing them as lunacy. Are terrorist really driven by a desire to enter Paradise? Do they really take up murder simply because they are the most sincere and devout of Muslims and simply because believe jihad is commanded by Allah? Does Atran really blame male bonding in soccer matches for terrorism! Perhaps this post will help shed a little light on where Atran is coming from.)

Here I outline the career, thoughts and feelings of one such interviewee as I came to understand him through the detailed interview and description of time spent with him by Atran. Most of the material is based on chapter 8, titled “Farhin’s Way”. Farhin is the Indonesian terrorist interviewee.

Of course this post can only be my own understandings based on my own reading of Atran’s book. To best grasp the character of Farhin it is best to read the book for oneself. One thing should emerge by the time one has finished this chapter (or even this post) — Farhin is driven by more complex motivations than the Islamic faith that millions follow today. Harris has even suggested it is the ecstatic hope of Paradise that drives suicide bombers. There is no place for such a simplistic (and fictional) view in Farhin’s mind. And the Farhin case study is found in many ways repeated many times over among the other terrorists whose lives we learn about in this book.

The chapter opens with a description of three Bali bombers who were executed by firing squad.

Their last social act while alive was to shout the words, “Allahu Akbar” (Got is Greatest), at their executioners, who then shot them each dead through the heart. (p. 119)

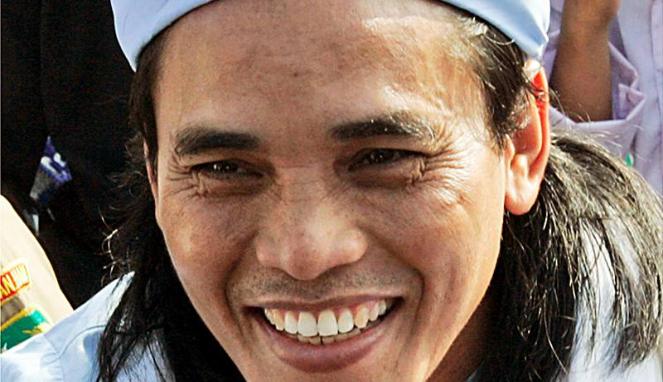

Amrozi, the “smiling assassin”

Amrozi, the “smiling assassin”

One of these young men, Amrozi, was known in the media as “the smiling assassin” because of his ever-present grin throughout his trial.

Those who knew Amrozi as a boy remembered him as very friendly, always wearing a happy smile, and forever playing pranks on his teachers and classmates. He had no interest in school-work or studying the Koran and was expelled from junior high school. He loved motorbikes and taking girls for rides on them. He became known as Mr Fixit man, “repairing everything from cell phones to cars.” “But he seemed to have no center.”

.

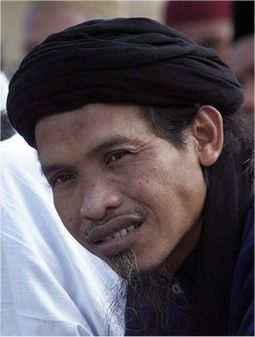

Mukhlas, the so-called “ascetic”

Mukhlas, the so-called “ascetic”

His older brother, Mukhlas, was quite different. He chose the ascetic and religious life. He worked as a goat-herder. His friends taunted him for his prudishness. (Once they locked him in a room with a prostitute but he refused to touch her.) The press later made much of Mukhlas’ life-choice and read into it some deep psychological flaw. In fact, Mukhlas went on to become a happily married man, a loving father and kind to his friends and students. Most of these admired and even adored him, though they had nothing to do with terrorism.

.

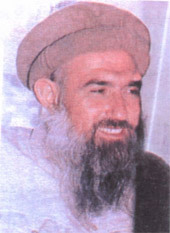

Samudra, the idealistic achiever

Samudra, the idealistic achiever

The third man executed that morning was known as Imam Samudra. His parents were working class adherents of a Saudi Wahabi form of Islam. Samudra himself, however, disliked religious study and having to memorize the Koran. He said:

I was not so motivated with the Islamic schooling system. I often skipped class. . . . Once it got to be about two o’clock in the afternoon, i would feel sleepy. It was so boring.

His favourite interests were “science, electronics, computers, chess, and poetry.” He excelled at all of these and was top of his high school class.

He knew he had ability and wanted to use it in the service of a great and good cause, as his martyred heroes had done . . . Malcolm X and S. M. Kartosoewirjo.

Farhin

In 2005 Scott Atran flew to Indonesia to interview the Bali plotters, but a change in prison warden put an end to prearranged plans, so he flew on to Sulawasi to interview Muslim fighters in Sulawesi, one of whom was Farhin bin Ahmad.

How did Farhin become involved with the terrorist organization (JI)?

When Farhin was 20 years old a man from a Darul Islam visited his father and asked if he knew someone who wanted to go to Afghanistan to help the Muslims there fight against the communists. His father told him, “Yes, here’s my son.”

Who was Farhin’s father?

His father’s name was Ahmad Kandai. In 1957 Kandai attempted to assassinate Indonesia’s President Sukarno with a hand grenade. He was tried, jailed and later released. All his sons became jihadis. Kandai strongly believed in the goals of Dural Islam to establish Islamic rule in Indonesia but did not give any of his children a religious education. He sent them all to secular schools.

On his way to Afghanistan in 1987 Farhin stopped off in Malaysia to spend time with an Indonesian instructor, Abdullah Sungkar, who gave him religious teaching about jihad and physical training — crawling over the ground, running, jumping, martial arts (but not with weapons).

He then flew to Pakistan with a small group on Pakistani visas. They did some more training there at a refugee camp, then moved on to a new camp near the Khyber Pass and five kilometers from the Afghan border.

For 2 years at this camp (Camp Saddah) he trained and studied with the other Indonesians: 6 months basic training then 6 months intensive training in infantry tactics, weapons, demolition and explosives, intelligence and map reading. He trained for one more year then gave crash courses to others going into battle yet who don’t have time for the full training course.

Over that period of three years he got to go on holiday nine times. (Holiday is their term for leaving the tedious work of training and going into the war zone.) There he mostly engaged with the Soviet army. “That was our vacation and we all prayed for more of it. Our commander was Afghan . . . ”

When pressed to explain more about those three years Fahrin said the time was not only spent in training and fighting but also in studying. About 70% of his time was studying al-ʿAqīdah aṭ-Ṭaḥāwiyya or “The Fundamentals of Islamic Creed” and about 30% preparing for battle.

Abudullah Azzam came to speak to them and taught them that they “should carry out jihad wherever Muslims are colonized.”

After the communists were defeated and driven out of Afghanistan Farhin began to make his way home.

He stopped again to stay with his teacher and trainer in Malaysia, Abdullah Sungkar. Farhin helped with work on his chicken farm to make some money and help Sungkar’s organization that had trained Indonesians for jihad in Afghanistan.

Fahrin then returned to Jakarta, Indonesia, where he earned his keep selling gadgets and smoked food in the streets. He met up with other Afghan Alumni (war veterans) who got together once a week to discuss religion and do some physical training: “martial arts, swimming, but mostly soccer.”

Then in 1993 one of the Indonesian trainers he knew from the Khyber Pass camp in Pakistan (Zulkarnaen) came to see Farhin.

Zulkanaen asked Farhin if he would be loyal to Sungkar (the trainer in Malaysia). It turned out Sungkar had rejected another person who preached “Sufi” ways which he did not regard as “pure Islam”. Farhin agreed.

President Suharto fell in 1998 and Sungkar returned from Malaysia to live again in Indonesia. So also did Abu Bakr Ba’asyir — who became the leader of a new organization that replaced Darul Islam, JI (Jamaah Islamiyah). Sungkar died soon afterward, too.

After this more Indonesians who had trained with Sungkar returned to Indonesia with the hope of fighting to help Muslims in Indonesia itself.

In August 2000 Farhin helped in the attack on the Filipino ambassador. He drove the truck with his brother and the bomb that devastated the Philippines ambassador’s residence in Jakarta. (His brother was caught.)

A month later Farhin was asked to go to Poso in Sulawesi to set up a branch of Kompak: He set up both its charity wing and its military wing. “Every charity needs an attack group to protect it.” This is because no charities are allowed to help any such groups associated with JI. The relations between Kompak and JI are informal. Farhin himself was never an “official” member of any organization. Relationships are based on mutual trust.

Question posed to Farhin: “People who are a part of JI, friends of yours, have killed civilians, not in battle but in suicide bombings, including Muslims. What do you think of that? What did you think of the Bali bombing?”

Farhin: I don’t know all the conditions. Some people say the bomb was an Israeli or American bomb.

Atran: But people you know — Imam Samudra and Mukhlas — say they did the Bali bombing and are proud of it. Sumadra trained the suicide bombers. Mukhlas blessed them all.

Farhin: I know, the probably did the small blast to frighten away people from drunkenness and molesting women, but the big blast was too powerful. Somebody else may have done it.

Atran: Samudra and Mukhlas say it’s OK to kill other Muslims for their cause.

Farhin: It’s not good to kill Muslims, I don’t know if they really believe that, but it’s not good. I wouldn’t do that. I fight only those who fight us, and I support those who fight elsewhere, in Bosnia, Chechnya, Iraq against those who fight to colonize Muslims. But I stay here.

Atran: Where’s here?

Farhin: Here in my country where Muslims are being killed.

Before this interview Farhin had been Atran’s traveling companion and bodyguard. During their journeys Farhin received news that swelled his eyes with tears. He had just heard of the death of a young man killed in a skirmish with Christian fighters. Atran asked Farhin if he knew the man.

No, but he was only in the jihad a few weeks. I’ve been fighting since Afghanistan [the late 1980s] and I’m still not a martyr.

Scott Atran reminded him that he loved his wife and children. Farhin’s reply was to say Yes, he did, God has given him his family, and he must have faith in the path God has set out for him.

That way or path that he desired was the way of the mujahid, the holy warrior. He had studied in Pakistan with the same Palestinian scholar (Abudullah Azzam) who had been Bin Laden’s mentor. Later he hosted the future 9/11 mastermind Khaled Sheikh Mohammed in Jakarta.

Farhin firmly believes that only in fighting and dying for a cause is their nobility in life.

Again, War is noble in a true cause that is worth more than life.

Scott Atran wanted to know what kept the “Afghan Alumni” together after the Afghan war had ended. They remained together in the years after the Afghan war and before JI was started up. How?

We Afghan Alumni never stopped playing soccer together. That’s when we were closest together in the camp . . . except when we went on vacation [to the battlefront] to fight the communists.

Just to be sure, Atran asked again what really kept them together:

We played soccer and remained brothers — in Malaysia, when I worked on the chicken farm, then back in Java.

Atran:

Maybe, then, it was something about the relation between God and soccer that was eluding me. Maybe people don’t kill and die simply for a cause. They do it for friends — campmates, schoolmates, workmates, soccer buddies, bodybuilding buddies, paintball partners — action pals who have a cause. Maybe they die for dreams of jihad — of justice and glory — and devotion to a family-like group of friends and mentors who act and care for one another, of “imagined kin,” like the Marines. Except that they also hope to God to die.

Then it came on me as embarrassingly obvious: It’s no accident that nearly all religious and political movements express allegiance through the idiom of the family — brothers and sisters, children of God, fatherland, motherland, homeland. Nearly all major ideological movements, political or religious, require subordination or assimilation of the real family (genetic kinship) to the larger imaginary community of “brothers and sisters.” Indeed, the complete subordination of biological loyalty to loyalty for the cultural cause of the . . . “Brotherhood” of the Prophet, is the original meaning of the word Islam, “submission.”

But what is it that binds imagined kin into a “band of brothers” ready to die for one another as are parents for their children? That gives nobility and sanctity to personal sacrifice? What is the cause that co-opts the evolutionary disposition to survive?

The answer to this should be reserved for a future post.

President Obama has said that he cannot empathize or pretend to penetrate the “blank stares of those who would murder innocents with abstract, serene satisfaction.”

In fact, the eyes of the terrorists I’ve known aren’t blank. They are hard but intense. Their satisfaction doesn’t lie in serene anticipation of virgins in heaven. It’s a visceral as blood and torn flesh. The terrorists aren’t nihilists, starkly or ambiguously, but often deeply moral souls with a horribly misplaced sense of justice. Normal powers of empathy can penetrate them, because they are mostly ordinary people. And though I don’t think that empathy alone will ever turn them from violence, it can help us understand what may. (p. 5)

Look at how most Muslim mujahedin answered the following set of questions. Note the irrationality of the final response — at least it is irrational from our perspective of standard economic or political calculations and trade-offs. The apparent “irrationality” of the response tells us much that is critical to understanding the mind of the jihadi. (It also demonstrates that Harris’s explanations for terrorism is fictional.)

- Question A: Would you give up a roadside bombing if it meant you could make the only pilgrimage to Mecca. Most answered Yes

- Question B: Would you give up a suicide bombing to instead carry out a roadside bombing if it is possible? Most answered Yes.

- Question C: Could you give up a suicide bombing if it meant you coud make the only pilgrimage to Mecca in your lifetime? Most answered No!

If A is preferred to B, and B is preferred to C, then A must be preferred to C — but that’s not what has happened here.

A pilgrimage is preferred to a roadside bombing, a roadside bombing is preferred to suicide bombing, but a pilgrimage is NOT preferred to a suicide bombing!

Again, this is leading to questions that must await another post. (The priorities here certainly belie the claims that a longing for the ecstasies and virigins in paradise is the driving motivator of terrorists!)

Atran concludes his eighth chapter by noting the way Indonesian, Turkish and Saudi police forces are learning to understand the minds and motivations of would-be terrorists and have had significant successes in their anti-terrorist programs accordingly. They have learned to treat the problem more as a public health matter than a criminal one.

One of the brothers of the executed Bali bombers, Ali Imron, was spared the execution because he expressed remorse for his role in the bombing. The leader of Indonesia’s national police strike team Antiterrorism Detachment 88, Tito Karnavian, has been responsible for tracking down the leaders of the JI terrorist organization. He has also embraced Farhin and Imron.

Tito points out that Ali Imron has helped to turn more people away from violence than he imagined. . . . [A] top FBI official who was on hand remarked: “Maybe that works. Maybe it’s the smart thing to do. But . . . can you imagine me hugging Timothy McVeigh? They’d have me hanging by my balls from the dome of Congress!

(Of course, Indonesians still shoot unrepentant terrorists.)

Mercifully Atran is able to write that U.S. policy has begun to shift towards treating terrorism as a social and public health issue rather than a strictly military and police problem — at least in Afghanistan. Unfortunately, the earlier images of America’s approach — such as Abu Ghraib — will probably remain the dominant images in the minds of Afghanis generations from now.

So what is Farhin doing now? Selling coconut wood and tending a small plot of cacao land. His second wife has delivered their second child. He wanted to improve his Arabic and English, but said he was ready to take up arms again “if Muslims are attacked.”

I don’t know if he has managed a transmigration to a more peaceful soul or how keen he still is on martyrdom, but at least he seemed to have shied away from killing noncombatants.

He even said he is willing to come to America to explain how he sees things and to try to understand what others see.

When I brought up this offer, and similar proposals from other jihadis, at the White House, the State Department, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Senate, the House, and the FBI, some people laughed, others seemed bemused, and most rolled their eyes.

It seemed that the idea of talking to our enemies to find out why they are our enemies could only come from Planet Fruitcake. (p. 133)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

-No, he didn’t.

Of course he didn’t, and the point would be quite irrelevant to the return Indonesian jihadis to Indonesia. Most careless of me. Have corrected the sentence.

Thanks Neil.

As a Muslim, I have wanted to understand this (“Jihadi”) problem and this post was most informative. I had read previously of the Saudi approach of treating it as a mental health problem and “deconversion” from a harmful ideology.

I found this sentence amusing—

—Perhaps he is referring to U.S. soldiers who sit in front of a computer and manipulate drones that kill innocent civilians?—Maybe he cannot “empathize” but he is enthusiastic about his drone program—which has apparently escalated since he took office…!!!…..

I am not certain I understood this one—

—This does not fit mainstream Islamic thought (subordination of genetic kinship). The Quranic “system” is set up to be in harmony and balance between both the micro and macro level—therefore loyalty begins in the home–between parents and children, is then broadened to extended relations/friends etc and then to the community, from there to the nation and finally extended to all humanity. It is possible this idea may have been twisted for Jihadi purposes?……..

The reason Islam is not an organized religion is because the relationship between God and man is an individual one. Family and community provide support and companionship for the spiritual journey but ultimately one is accountable to God as an individual only. (here again there is a balance between micro and macro/individual and humanity)

As to this statement—

My memory might be faulty, but at that time there was speculation that the U.S. did not want to be seen as a lone target—it wanted a “Global War on Terror”. Therefore “terrorists” needed to be “produced”. The “You are with us or against us” mindset—to some countries dependent on U.S. trade (at that time)—it meant a warning. Initial reports said the bomb was military grade—but this was later changed…..may or may not have been a cover-up. Of course there are many conspiracy theories……….Nevertheless, it is interesting that all “roads” seem to lead to Afghanistan (Soviet-Afghan war).

I think a couple of your responses are eliding faith-definitions and scholarly terms. These need to be kept separate. Your reason for denying that Islam is an “organized religion” would just as well apply to the self-definitions of a host (even most) of Christian sects and divisions. Your definition or reason could well be repeated by many if not most or even all of these.

The discussion of “fictive kin” or “imaginary brothers and sisters” is not derogatory but merely a scholarly expression for the notion of embracing as “brothers and sisters” (or “family”) any group wider than one’s own immediate blood relations on the basis of a common faith. (Christianity has the same notion of sons and daughters of the deity, etc.)

I don’t buy, and nor does Atran, the idea that the Bali bombing was anything but the work of the convicted terrorists (and those associated with them but pardoned). Australia and the UK were firmly on board with the U.S. from the moment of 9/11. There was no need for any other stimulus to get them onside. Farhin appears to be in some sort of denial in a manner not unlike the parents of some of the 9/11 bombers — the father of one, at least, refuses to believe his son was involved, or if he was, then he believes he must have been tricked. I read Farhin’s dismay in the same context.