Nearly everything I learned in high school about early Roman emperor-worship was wrong. Luckily before I die I’ve since read The Son of God in the Roman World by Michael Peppard and I can now go to my grave with one more misconception eradicated from my mind.

I had once been taught that the people who participated in the forms of emperor-worship did not really believe their object of worship was a god (unless, perhaps, they lived in that more benighted oriental half of the empire). Living emperors, I was told, were not worshiped in those earlier years of Pax Romana. They had to die first. Hence Vespasian’s quip on his death-bed: “Oh dear, I think I’m becoming a god!”

The gulf between the material world and gods was, at least in the West, absolute. Emperor-worship was little more than a game of empty flattery from below and political manipulations from above.

We know better now. That’s not how it was at all. What misled us into the above notion of how things were was our reliance upon the writings of the philosophers like Cicero as the gateway to understanding how everyone else thought and acted. Archaeological and cultural studies research has since demonstrated that worship of the living Roman emperors was widespread from the earliest days of the empire. There was no sharp Platonic gulf between humans and gods among the general populace and imperial institutions.

So what does this have to do with the Gospel of Mark?

How to write about a Son of a Celibate God?

Michael Peppard opens with a little mind game of trying to imagine how an author who wanted to write down for others lots of the stories he had heard about a Jesus who supposedly lived a good generation ago and who was considered to be the Son of God. How would he start, especially given that the god in question was known not to procreate? The clue, Peppard says, lay in that author’s cultural environment. All about you were images, symbols, reminders of your emperor.

I cannot accept Peppard’s presuppositions in his mind-game. The Gospel of Mark is clearly not a collation of reminiscences that someone has collected and cherished over years and wishes to share with others in writing. Such authors have little reason to write anonymously or conceal their sources. Nor do they leave literary clues that their stories are for most part adaptations of other popular narratives such as those found in the Hebrew Bible. Nor do they write cryptically or metaphorically (with unexplained characters, behaviours, sayings and bizarre endings) to convey esoteric theological messages.

But I do believe Peppard asks a valid question. How would an author who knows the theological systems found in writings like those of the letters attributed to Paul begin to tackle a metaphorical narrative (a parable, if you like) to portray his beliefs about the Son of God? As Peppard writes:

[H]ow could he put this proclamation [the central Christian kerygma] into narrative form, especially if the God of Israel had no partner? Where would one begin? It is extremely difficult to imagine his situation as an author, writing before there existed other narratives of Jesus’ life. Especially if one is a Christian or a scholar of early Christianity, this requires some disciplined forgetting: Chalcedonian christological orthodoxy, the philosophical foundations of Nicea, the emanations of neo-Platonism, the procreative cosmologies of the Gnostics, the logos Christologies of Justin or John, and the virgin birth narratives of Matthew and Luke. But then what remains? The resources available to Mark: his Jewish traditions and his Greco-Roman world. With these resources, how could Mark best narrate the kerygma about the divine sonship of Jesus Christ? (p. 86)

Don’t Misunderstand Roman Imperial Adoption

Peppard warns readers not to jump to conclusions when he argues that the baptism of Jesus in Mark’s Gospel is a declaration of God adopting Jesus as his son. That a word carries unfortunate connotations of heresy and an unworthy low christology for most modern readers. Mark was writing for readers in a culture of Roman ideology. That changes everything.

But Mark’s Christology can be interpreted as “adoptionist,” if by that term one means that Mark narratively characterizes Jesus in comparison with the adopted Roman emperor, the most powerful man-god in the universe. (p. 95)

I have highlighted the words “narratively characterizes”. This is consistent with reading Mark’s Gospel as a parable of sorts, or a metaphor. Difficulties arise only when we come to the story with assumptions of historicity. Let’s just treat it for what it patently is for now — as literature. If there’s anything historical behind the narrative that can be a question for another day.

What is critical to understand that adoption in the Roman world did not imply an inferior status within a family, in particular within the Roman imperial family. One who was adopted as a son of an emperor was thereby given a higher status with respect to imperial honours and inheritance than a biological son.

[A]doption was how the most powerful man in the world gained his power. (p. 95)

This practice of adoption did not start relatively late in Roman history when the aged emperor Nerva adopted Trajan to succeed him, as I had been taught at school. Julius Caesar adopted his nephew, Octavian (Augustus), to succeed him; Augustus adopted Tiberius; Claudius adopted Nero in preference to his natural son Britannicus; and then an unfortunate adoption that went wrong when Galba adopted Piso. When Trajan was adopted to succeed Nerva, Pliny wrote a panegyric praising the wisdom and goodness of the ideology that the most meritorious person of all should be adopted to become Caesar.

(Peppard works with the conventional date of the Gospel of Mark being composed around 70 CE. I believe his interpretation of this Gospel works best if it were in fact written no earlier than the time of Trajan. There are other reasons for dating it no earlier, one of which is external evidence for the persecutions of Christians that the Gospel clearly presupposes.)

Between the Dove and the Centurion

There is a lot to cover in Michael Peppard’s book, too much to cover here. I hope in future posts to be able to return to his arguments on the meaning of God’s words at Jesus’ baptism that are most commonly translated into English as “This is my beloved son in whom I am well pleased”. (That last clause can also mean “whom I have chosen”.) Also of note are his reviews of previous literature. Roman beliefs and practices relating to genius, numen, “son of god” as opposed to “son of Zeus” or “son of Apollo”; Jewish evidence for similar concepts, second and third century literature tracing the evolution of our current concepts, and so forth.

So I’ll focus here on just one more detail. What did an adopted son of a god (emperor) have to do to win acceptance and recognition as the rightful new emperor?

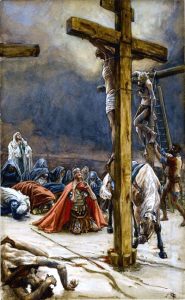

Many commentators have questioned the significance that it was a Roman centurion who declared, at the end of Jesus’ life, “This was indeed god’s son”.

Peppard’s thesis — that this Gospel is depicting Jesus as a son of God in opposition to the Roman emperor who was then worshiped as a son of god — throws interesting light on this declaration by the centurion.

First, recall my previous post, Jesus and the Dove – How a Roman Audience May Have Read the Gospel of Mark. (That post is itself an all too brief hint at Peppard’s argument for the baptism of Jesus being compared to the “good news” of a Roman imperial succession.) That’s the starting point for what follows.

Further, anyone who has read T. E. Schmidt’s Jesus’ Triumphal March to Crucifixion will appreciate much more what follows than those who haven’t. I outlined some of Schmidt’s key points in Recognizing the Triumphant Conqueror in Mark’s Crucifixion Scene.

Let us recall that the charismatic authority of the Roman emperor was derived in part from military achievement and concomitant military acclamation. Before the emperor could be divi filius, he must first be regarded as a “commander” (or imperator, the source of the English word “emperor”). Even adopted imperial heirs needed to prove themselves in battle and gain the approval of (enough of) the army. An emperor could simply not accede to the principate without it.

Returning to Mark’s characterization of Jesus, we can see some events with new eyes. Jesus’ “battles” are mostly with unclean spirits, the exorcisms of which have been interpreted fruitfully through postcolonial criticism — the Roman colonizers being symbolized as the “spirits” convulsing the people of Palestine. Mark cues the reader toward this interpretation in the exorcism of the Geresane demoniac, in which Jesus purges and fantastically destroys the violent and indomitable “legion.”

After his battles are completed, and after his status is announced above the site of imperial worship in Caesarea Philippi [the site of a Roman imperial temple where the other son of god was worshiped], Jesus marches into Jerusalem in a mock triumphal entry (11:1-11).

While there, he initiates a direct comparison between his father, the God of Israel, and the father-son gods imaged on the Roman coins (12:15-17). He declares himself to be the son of the God of Israel (14:61-62), but is mockingly clad in imperial purple by Roman soldiers of the praetorium (15:16-20).

The first and final public declaration of Jesus’ divine sonship — the statement of the centurion, “Indeed, this man was God’s son” — is perhaps explained best by colonial mimickry. Roman power, concentrated in the figure of the military, is at once both the challenge to and the legitimation of Jesus’ divine sonship. Up to this point, Mark had narratively characterized Jesus as a counter-emperor, a “son of God” whose rise to power in the cosmos had mimicked imperial power on a kind of parallel cursus and triumphus. Now the course ends with a mockery and subversion of the triumph. But with the Roman centurion’s cry, the parallel tracks of analogy and reality converge . . . : the acclamation of the army was in reality a necessary element of imperial power, and the death of an emperor was in fact the time when his exalted status was finally evaluated. (pp. 130-131, my formatting and emphasis)

Peppard extends the analogy by pointing out that the land of Israel was about to be usurped by the Roman legions and their divine father. (Most commentators, and Peppard himself, set this in the time of Vespasian. It fits even more neatly, I think, in the time of Hadrian, who was much more a venerated “son of god” at the time of his subjugation of the land. God gave a sign, however, that the inheritance was really about to be transferred to his son with the tearing of the curtain in the temple. It’s not how Peppard expresses it, but I see this as an indication that God is leaving only the abandoned material possessions to the Romans while the real spiritual heirs and inheritance is transferred to his Son.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I feel like we are finally starting to arrive at the real meaning and purpose of The Gospel of Mark after 2,000 years of obfuscation and misunderstanding. The most important step toward that goal is the realization that Mark was *not* collecting oral history and writing a “Greco-Roman biography” with some legendary elements, as all modern theologian-historians (including Peppard) assure us. He was writing sacred myth. Mark’s shaky command of Koine betrays his first language (Latin, not Aramaic), but his imaginary power was as huge as Tolstoy’s.

The Christians did not participate in the Imperial cult, and rejected the idea that the emperor was a god. This is why they were persecuted, and also why they needed a sacred text laying out their rationale for not worshipping the emperor. The Jesus myth grew out of their rejection, not the other way around. They knew that Vespasian or Hadrian were not sons of God, but they needed an explanation for why their god Jesus fit that role.

The Roman victory in Judea played a major role in Mark’s conception. The Romans had defeated the Jews because God was on their side, and the “adulterous and sinful generation” of Jews had supposedly rejected God. Mark needed to portray Jesus predicting the fall of the temple in the Olivet Discourse while simultaneously diminishing the victory of the Romans as venerating the emperor as God’s chosen son. Having a Roman centurion be the first person to recognize Jesus as “the son of God” after the crucifixion was not an accident.

This also helps explain the otherwise obscure connection of the word “euangellion” between how it was normally used by the Imperial mythology and its adaptation by Mark, to assure his listeners that the “real” good news was that Jesus, not Vespasian or Hadrian, was the son of God.

Peppard, Crossan and no doubt others have much to say about that word “euangellion” that you address in your conclusion. It’s worth a post in its own right.

Interesting… thanks for the information By the way did you know that Francesco Carotta (Jesus Was Caesar, ch. iii, “Crux”) has figured out that at the Funeral of Julius Caesar, is wax image was affixed to a cruciform tropaeum? (The rest of his hypothesis I take with a grain of salt.) And Justin Martyr quips in his I Apology 55 that the Romans did this or something similar for all the Emperors: “on/with this schematic you consecrate the images of the Emperors and with inscriptions dedicate them as gods.”

Interesting. (I wish now I had taken more time with Carotta’s book to notice details like this.)

Tropaeum — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tropaion

An extract from Corotta on Caesar’s effigy being attached to the tropaeum at his funeral: http://www.carotta.de/subseite/texte/jwc_s/crux3.html#note181

Yes, Carotta’s work has a treasure trove of details, indicating that mark may have been plaigarised from or evolved from a lost biography of Julius Caesar. But the one thing missing from Carotta’s hypothesis is: what was the motive for a plaigarism? And an evolution from the one to the other to me doesn’t make sense.

Now I’m glad Blood has posted before I did. he’s provided one possible motive for the plaigarism. But that doesn’t mean the Christians didn’t also crib from Homer (MacDonald), Josephus (Atwill, despite his conspiracy theory) and the Tanakh (Robert M Price). ;^)

Great post & comments, does there exist a great book that conclusively and thoroughly deconstructs “Mark’s” gospel or do I have to wait for one to be written?

I believe I have read several 😉

But no, each one really does, on reflection, lead to more questions and yet another resolve to re-read the Gospel through new perspectives, as no doubt you well know.

I have been invited to present a paper on “Christ the Conquered King: Further Reflections on the Triumph in Mark,” in which I critique Schmidt’s thesis. For me, Jesus is the conquered king of the Jews, executed at the climax of the triumph, and not the emperor celebrating a triumph.

This makes me rethink Mark’s Latinisms (like Centurion – literally Latin for “leader of 100”; Luke/Matt translate “leader of 100” literally into Greek). The Latinisms might have been done on purpose to cement the idea that Jesus is a counter-emperor.

Michael Peppard argues that the evidence suggests Rome as the most probable location of the composition of the Gospel of Mark. (I don’t think the Roman parody allusions are undermined in the least if the Gospel were composed in Antioch or Alexandria — or pretty much anywhere in the Roman empire by anyone in contact with others who had at least passed on details of a Triumphal Procession in Rome.)

Peppard points to the traditions of Peter’s association with Mark, of course. (But we also have early associations of the gospel with Basilides!) Peppard acknowledges the general distrust of patristic evidence so leans most heavily on internal evidence, in order of specificity:

1. Latinisms

2. Errors of Palestinian geography (5:1; 7:31)

3. Explanation of Jewish customs

4. Connections of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (resonances of Markan terminology, theology, community concerns, and ‘the tantalizing “Rufus”‘)

5. Motifs of persecution and martyrdom.

My own response to these:

Against Latinisms, we also have Aramaicisms, of course. Though these have their own literary explanations (e.g. adding atmosphere to the magic of performance of a miracle). I don’t know of Latinisms can be interpreted as a tool for literary effect. Latin was used more widely than in the city of Rome itself, of course, but nonetheless, as Peppard says, Latinisms do point to “a Roman context”.)

Against the geographical errors of 7:31 we have the argument of deliberate allusion to Isaiah’s prophecy: http://vridar.wordpress.com/2010/08/06/mark-failed-geography-but-great-bible-student/ and against those of 5:1 we have textual variants that point to literary allusions quite unexpected if we read the gospel literally/historically: http://vridar.wordpress.com/2010/10/10/jesus-and-heracles/ (also at vridar.wordpress.com/2012/03/23/jesus-journey-into-hell-and-back-told-symbolically-in-the-gospel-of-mark/ )

Explanation of Jewish customs can point to any writing intended for an audience beyond Palestine or a Diaspora community

The letter to Romans is actually evidence against the Patristic tradition of associations of Peter with Mark in Rome — upon which the Roman provenance most heavily relies.

Persecution and martyrdom — the pre-second century evidence for this anywhere, especially Rome, is open to serious doubt.

(Peppard acknowledges there are counter arguments to each of his points — though not necessarily the ones I have given here.)

But back to the Latinisms:

1. Mark, uses specific Latin terms to explain Greek words (12:42; 15:16)

2. There are also many other individual Latin words (e.g. see http://vridar.wordpress.com/2010/12/06/roll-over-maurice-casey-latin-not-aramaic-explains-marks-bad-greek/)

3. And also awkward Greek phrases that can be explained by linguistic interference from Latin.

4. The term “Syro-Phoenician” is only evidenced from the West at the time of Mark’s composition.

Peppard concludes that even if the Rome-Syrian debate on internal evidence is at a stalemate, the external tradition favours Rome.

But he concludes wisely that we must keep in mind that Christian leaders traveled. The author could well have been born in Jerusalem, traveled often to Antioch, and later arrived at Rome.

Even many mainstream scholars have a big problem with seeing GMark as Petrine. So I can’t help wondering whether the tradition of Mark’s association with Peter arose from a (perhaps intentional) misunderstanding. If GMark was an allegory written by a disicple of Simon (of Samaria, that is) and someone wanted to co-opt it for proto-orthodoxy, how hard would it be to claim that the Simon in question was Peter?

Likewise for Clement of Alexandria’s statement that Basilides claimed to get his gospel from a disciple of Peter. Again, as I see it, he may indeed have obtained it from a disciple of someone named Simon but it is much more likely that the Simon in question was Simon of Samaria, not Simon Peter. Irenaeus says Basilides was a pupil of Menander, Simon’s successor.

Last, I am wondering if any readers of this blog know whether Mark of Caesarea has ever been proposed as the author of GMark. According to Eusebius, Mark of Caesarea was the first Gentile bishop of Jerusalem. He obtained that position after the Romans put down the Bar Kosiba rebellion and expelled all remaining Jews from Jerusalem. The last Jewish Christian bishop was presumably one of the casualties in the rebellion.

It strikes me that Mark, being from Caesarea Maritima in Samaria around 135 CE, may have been a Simonian. For Justin, writing about fifteen years after that, says “ALMOST ALL the Samaritans, and even a few even of other nations, worship him (Simon)…, ” and Justin complains that they have the nerve to call themselves Christians. Recall too that Caesarea was heavily Roman, being the capital of the Roman administration of Judaea. It was there that Roman prefect resided and it was also there that the Pilate Stone was found in the early 1960s. So Roman was Caesarea that Jewish rabbis early on referred to it as the “the daughter of Edom.” (The word “Edom” means “red” and was a known Jewish epithet for Rome. By the way, the Latin word for “red” is “Rufus,” as in “Simon…. the father of Alexander and RUFUS” – Mk. 15:21, my emphasis).

So these are a few of the considerations that make me think Mark of Caesarea would be an interesting candidate for author of GMark.

The language of the legions stationed in the East was Greek, but I think it probable that it was in essence a subcultural dialect of the Koine that contained a number of Latin loanwords. The author of Mark may have been a person who was or had been in close contact with elements of the Roman military and imperial administration somewhere in Syria. His Greek simply included as loans the terms that are identified as Latinisms.

Addendum: this would also account for familiarity with the tradition of triumphs, without positing that he was ever actually at Rome.

I wonder what a Baysean approach to these questions might produce. It would not be a definitive result but its advantage might be that it can indicate the best guesses possible given our state of knowledge and understanding of the evidence today.

I fear that this may become like the Documentary Hypothesis — a mutable chimera that grows and grows in complexity until it devours its’ own tail.

Woven into one narrative we have evidences of:

– Septuagint midrash

– Homeric mimesis/Greek myth

– Q, or “the Logia of Jesus” (per MacDonald)

– Roman imperial theology used ironically

– Pauline Epistle influence (?)

– Josephan influence (?)

– Aramaisms

– church tradition

Such a diverse multiplicity of sources surely would have gone well beyond what was needed or expected of a Bishop or scribe writing a church manual. The author only needed to write the passion along with some wise parables from the master and a few quotes from the Prophets. Was Mark a genius or a madman?

Woven into one narrative we have evidences of:

– Septuagint midrash

– Homeric mimesis/Greek myth

– Q, or “the Logia of Jesus” (per MacDonald)

– Roman imperial theology used ironically

– Pauline Epistle influence (?)

– Josephan influence (?)

– Aramaisms

– church tradition

– Influence from life history of Julius Caesar (?) (per Carotta)

That’s quite a list! The last addition is mine — particularly when Carotta claims the Passion Narrative is based on the funeral of Julius Caesar; I can see at least a partial basis and the late German theologian Ethelbert Staufer (Jerusalem und Rom) (Christ and the Caesars) discovered the Church’s liturgy of the Passion definitely was based on the ceremony of Caesar’s funeral. A Baysean analysis is certainly warranted.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/56409325/Christ-and-the-Caesars-Historical-Sketches-ETHELBERT-STAUFFER

“The Gospel of Caesar” (film) http://web.archive.org/web/20140822004402/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wwfY069iPVI

> . . Jesus purges and fantastically destroys the violent and indomitable “legion.”

Just a reminder to readers that it is often suggested that the Gadarene swine are there to identify “Legion.” According to Wikipaedia Legio X Fretensis gained fame in the successful siege of Jerusalem (70 A.D.). Thereafter, X Fretensis was solely responsible for maintaining order in Judaea.

Among the several mascots of X Fretensis was the “boar.”

Hi Neil,

Your conjecture that the Gospels’ usage of the term ‘son of god’. “fits even more neatly in the time of Hadrian” than the Flavian Judean campaign, is demonstrably incorrect.

Jesus was the Passover lamb of the New Covenant and therefore required a forty-year cycle to mirror the one that established the first covenant. (Note that the NT even provides a ‘Pentecost’ at the correct place in time to establish the cycle’s existence.) The Gospels authors’ back-calculated Jesus’s ‘death’ to Passover 33 to be able to begin their forty years of wandering which came to an end, of course, at Passover 73 with the fall of Masada and the Romans gaining full ownership of the Promised Land.

The perfect forty-year cycle between the sacrifice of the new Passover lamb and the Romans ownership of the Promised Land could not have been circumstantial. It is odd that modern NT scholarship completely misses the fictional construction of dates in the NT and Josephus in that it was so widely understood byy earlier critics. Whiston was aware, for example, that the AoD occurred at the mid-point of the ‘week’, which would have also come to an end at Passover 73.

Moreover, the expression “This is my beloved son in whom I am well pleased” is also obviously Flavian typology. The Gospels’ event occurs at the same location as the beginning of Titus’s campaign to Jerusalem who – like the Gospels’ character – is about to ‘fish for men’ on the Sea of Galilee. A ‘dove’ is mentioned to reference Titus whose name means dove in Latin.

http://www.name-doctor.com/name-titus-meaning-of-titus-6169.html

Hope this is useful

Joe

The post was written four years ago and I am perhaps even less confident in assigning composition dates to the gospels now than I was then. But Joe, your arguments are entirely speculative. Before we could give them any sort of weight we should ask what we might expect to appear in the explicit evidence (not in further speculation and rationalisation) if they were true.

Example: we have no evidence to support the view that the evangelists believed the crucifixion was in the year 33. That’s entirely a speculative claim to support a lot of other speculative scenarios. Further, the wider significance you attribute to the “fall of Masada” re any “wandering” is based on a naive reading of Josephus’s narrative and further speculation.

There may be an intentional 40 year gap between the time of crucifixion and destruction of Jerusalem, but we have no evidence to establish such a hypothesis as a certainty.

Resting any assumption — much less an entire hypothesis — on the fixed date of AD 33, is pedantic folly. Far from a deliberate “back-calculation” by the evangelists, that date is but a desperate, modern grasp to reconcile Pilate’s tenure, the death of the Baptist, the report of Jesus being “about thirty” plus the 3-year mission in John, along with the vain attempt to pinpoint a year when the sabbath and Passover coincided.

The very near-impossibility of deriving an actual passion date from the vague & contradictory inferences show that the gospel authors didn’t give a damn about chronological precision or ‘perfection’.

Hi Neil,

Sorry, but I found your response to be a chain of non-sequiturs.

First, my point has nothing to do with the composition dates of the Gospels.

Second, your notion that; “Joe, your arguments are entirely speculative” is incorrect. Are you saying that Jesus was not established as the Passover sacrifice of the New Covenant? Or that there was no Pentecost in the NT placed into the correct date sequence?

Third, I do not believe that your sentence – “Before we could give them any sort of weight we should ask what we might expect to appear in the explicit evidence (not in further speculation and rationalisation) if they were true” – can even be diagramed. Want to give it another shot?

Finally, the statement I found the least coherent was your notion that “we have no evidence to support the view that the evangelists believed the crucifixion was in the year 33.”

Would you mind explaining how that date has been so widely understood as the year Jesus was crucified if there were “no” evidence?

Joe

This is laughable. – Can you diagram that sentence?

Hi Joe, no, I’m not interested in discussing the sorts of speculative suggestions you raise.

As for the specific date of 33 for the crucifixion, I have no idea why anyone would come down dogmatically for that or any particular date. I thought it was “widely understood” that no-one knows for sure the year of the crucifixion and dates within the range from late 20s to early 30s are variously suggested.

If there is evidence for 33 then just spell it out — Just saying the date of 33 is “widely understood as the year” gives me no starting point.

But if you don’t think further discussion between us will gain much for either of us or readers in general I’m happy to just break it off now.

If you are truly ignorant of the reasons why — which I alluded to above — I can’t imagine why anyone even bothers to give you the time of day.

Hi Neil.

You misunderstand my position as to the meaning of the year 33. The Gospels blended historical events with fictional ones to create New Covenant typology. Those who attempt to determine the birth date of Jesus by comparing historical data with the events of the Gospels are like someone trying to find the birthdate of Mickey Mouse by studying historical elements used inside of Disney cartoons.

The reason the year known as ’33’ is so designated as the year of the crucifixion is solely because the authors claimed that Jesus was “about 30” when he began his ministry and there are three Passovers mentioned in John. And, since we have chosen to begin our calendar with the Gospels character’s birth, his 33rd year is our year 33 by definition. The actual question is why do we call the year one the year one.

The authors indicated Jesus’ birth year by claiming he was “about thirty” during Tiberius’s fifteenth year as Caesar. Hence the year that was thirty years before the fifteenth year of Tiberius’s reign became what we now use as the year one.

So the year 33 is the year of Jesus’s crucifixion not because an historical event occurred in that year but because that is what the number statements in the literature concerning the character’s life span state. Here is your misunderstanding. My position that the character was crucified in his 33rd year is derived directly from the text and is why it has been generally understood. It is the other claims and conjectures concerning the dates of the character’s life that are speculation.

Moreover, since the authors were creating fiction and could choose any dates they wished, why and how did they select that particular date for the Passover Sacrifice of their New Covenant?

In order to logically conclude their New Covenant typology’s mapping onto the original Passover sacrifice they set this date at forty years from their full ownership of Judea – the date they claimed that Masada fell – Passover 73.

Trying to argue that the perfect forty year symmetry between the two Passover stories was not intentional is nonsensical in that the accident it posits is far too complex. (This as self-evident but we should work through it – the method they used to set up the fall of Masada in the year 73 is amusing.)

Having begun the absurd tale of a New Covenant beginning with a human Passover lamb at Passover 33 followed by a mirror of the Pentecost, the only date with which to conclude the story would be Passover 73. Thus it was not circumstance that Jesus was “about thirty” in the 15th year of Tiberius. This particular age could only have been back calculated from the conclusion of the Flavian campaign.

What the public really needs to see is that your position that Hadrian’s campaign is the “better fit” for the Gospels’’ story is indefensible. The Gospels record Flavian military victories. Some – like the fishing or men at the Sea of Galilee and the episode with the demons at Gadara – are presented symbolically; but others, such as the encircling of Jerusalem with a wall, the razing of the temple and the AoD are presented literally. All of them are presented in the same sequence as Josephus recorded them and they are all specific to the Flavian’s campaign, not Hadrian’s.

Hope this is useful.

Joe

If your writers’ collaborative wanted to clearly indicate AD 33, why oh why, when sitting down together to write the four gospels all at once, did they give two conflicting birth years for Jesus, and make Jesus’ mission last one year in three of the gospels but three years in the other one? Why not get all the hidden clues to corroborate across all four gospels? Why not just write one gospel?

Hi Matt,

Good questions. I suggest you read CM to get the complete answers but suffice to say errors and contradictions are used to hide the typology, as was the breaking the typology up into different Gospels and histories.

A bit I wrote about Jesus’s ‘spit miracle’ will illustrate this technique. (This is not in CM)

The most important concept of Mark 8 is the identification of Jesus as the Christ. Matthew and Luke also have versions of the ‘Christ identification’ story. While Luke’s version is an abbreviation, Matthew’s includes a different conclusion than Mark’s in which Jesus describes a ‘binding and a loosening’.

If you combined Matthew and Mark’s stories they would look like this,

22 they brought a blind man to Him, and begged Him to touch him. 23 So He took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the town. And when He had spit on his eyes and put His hands on him, He asked him if he saw anything. 24 And he looked up and said, “I see men like trees, walking.” 25 Then He put [His] hands on his eyes again and made him look up. And he was restored and saw everyone clearly. 26 Then He sent him away to his house, saying, “Neither go into the town, nor tell anyone in the town.” 27 Now Jesus and His disciples went out to the towns of Caesarea Philippi; and on the road He asked His disciples, saying to them, “Who do men say that I am?” 28 So they answered, “John the Baptist; but some [say,] Elijah; and others, one of the prophets.” 29 He said to them, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter answered and said to Him, “You are the Christ.” (Matthew begins here) “And I also say to you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build My church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it. 19 “And I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” Both versions end with Jesus instructing his disciples to keep his identification as the Christ secret.

So the concepts that the Gospels claim as occurring around the time of the identification of the Christ were a spit miracle that featured the odd concept of ‘men like trees’ and the prediction of a the disciples being given the key to the kingdom of heaven and ‘binding and loosening’. Jesus also instructed his disciples to keep his identity as the Christ secret.

As the story is obviously fiction, why did the authors choose these particular concepts to frame around the ‘identification of the Christ’ story?

In fact, these events were chosen to ‘foresee’ Vespasian being identified as the Christ.

In order to decode Mark 8 one first needs to understand where in the sequence of the Jesus/Titus typology the story occurs. I don’t want to go into complex typology here to position the parallel precisely, so suffice to say the Gospels’ ‘identification of he Christ’ story occurs after the demoniac of Gadara and before the Son of Man marches from Galilee to Jerusalem. In Josephus’s version this would be at Wars 4, 10 the chapter that contains the story of Vespasian becoming Caesar.

“. . . he (Vespasian) had not arrived at the government without Divine Providence, but a righteous kind of fate had brought the empire under his power.” Wars of the Jews, 4, 10,

The fact that by becoming Caesar Vespasian also became the “Christ” – in other words that the Jew’s messianic prophecies predicted the Flavians – was placed in another part of Josephus’s text.

“. . . what did the most to induce the Jews to start this war was an ambiguous oracle that was also found in their sacred writings, how, “about that time, one from their country should become governor of the habitable earth. The Jews took this prediction to belong to themselves in particular, and many of the wise men were thereby deceived in their determination. Now this oracle certainly denoted the government of Vespasian, who was appointed emperor in Judea.” Wars of the Jews 6, 5, 312-313

I will show why this was done below.

Though Josephus’ story of Vespasian becoming Christ does not have any obvious typological linkage to the Gospels’ ‘spit miracle’ it is typological. It was linked to the story of Exodus in order to show the beginning of the ‘new covenant’ predicted by Jesus and recorded by Josephus.

“Since it pleases god who has created the Jewish nation to depress the same and since all good fortune has gone over to the Romans” Wars Book 3, chapter 8, line 354

This linkage is to be expected as Josephus claimed that the Romans were replacing the Jews’ in God’s favor and therefore linked the story of Vespasian ascension to the OT’s story wherein the Jews first gained God’s favor. To show that the Romans were becoming God’s chosen people Josephus used the OT story of the passage through the Red Sea as a type for his description of the harbor of Alexandria. Though this may seem far afield from Mark 8, it relevance be will shown below.

First, Josephus links his description of the harbor of Alexandria to Exodus by describing it as “walled in” on the right hand and on the left. As is so often the case in the Flavians’ typological genre, notice that the parallel concepts between Josephus and the OT occur in the same sequence.

“And thus is Egypt walled about on every side. The haven also of Alexandria is not entered by the mariners without difficulty, even in times of peace; for the passage inward is narrow, and full of rocks that lie under the water, which oblige the mariners to turn from a straight direction: its left side is blocked up by works made by men’s hands on both sides; on its right side lies the island called Pharus,”

– which is linked to this passage in Exodus

So the children of Israel went into the midst of the sea on the dry [ground,] and the waters [were] a wall to them on their right hand and on their left. Exodus 14: 22

Once a reader recognizes that Josephus is mapping his story onto Exodus 14 spotting the connections becomes easy as they occur in the same sequence. Josephus therefore next depicts a fiery pillar:

“which is situated just before the entrance, and supports a very great tower, that affords the sight of a fire”

– which is linked to this passage in Exodus

“Now it came to pass, in the morning watch, that the LORD looked down upon the army of the Egyptians through the pillar of fire.”

Then Josephus describes the destructive power of the sea breaking through the “walls’ just as happened to the Egyptians;

“when the sea dashes itself, and its waves are broken against those boundaries, the navigation becomes very troublesome, and the entrance through so narrow a passage is rendered dangerous;

– which is linked to this passage in Exodus

“Then the waters returned and covered the chariots, the horsemen, [and] all the army of Pharaoh that came into the sea after them. Not so much as one of them remained.”

Finally, Josephus describes the safety of the passage “once you got into it.”

“yet it (the passage through the dangerous water) is the haven itself when you are got into it, a very safe one”

– which is linked to this passage in Exodus

“But the children of Israel had walked on dry [land] in the midst of the sea, and the waters [were] a wall to them on their right hand and on their left.” Josephus, Wars 4, 10 lines 610 – 615 and Exodus 14

Josephus’s subtle Exodus typology is important in that it shows that fictional typology linking to Exodus was being produced in the Flavian court. This suggests that the other story that used this genre – the Gospels – emerged from the same location. What is strange however is that Josephus does not describe Vespasian as journeying to Alexandria at this time even though his other court historians claimed that he made the trip. This absence will be explained below.

Mark’s Christ identification’ story is preceded by an odd tale about Jesus using spit to restore sight to a blind man.

“So He took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the town. And when He had spit on his eyes and put His hands on him, He asked him if he saw anything. And he looked up and said, “I see men like trees, walking.” Then He put His hands on his eyes again and made him look up. And he was restored and saw everyone clearly. Mark 8:22-26

This miracle has puzzled scholars in that Jesus’ powers seemed to have failed him as on his first try the man claims to see “men like trees” and Jesus had to lay his hands on the man a second time to get him to see clearly. This seems to require an explanation; why would the author record Jesus failing to perform a miracle? And what were the ‘trees like men’ the man saw?

The answers are found in the work of Suetonius, another Flavian court historian. Suetonius recorded Vespasian’s stay in Alexandria during the time which he was ‘identified as the Christ’ in the Gospels/Josephus typology. While he was in Alexandria Vespasian performed the spit miracle that was foreseen by Jesus’s parallel miracle in Mark. My conjecture is that the first edition of Josephus recorded the same miracle that Suetonius did at the point where Josephus recorded his harbor of Alexandria/Exodus typology. This episode was later removed by an editor of Josephus who deemed Vespasian’s ‘spit miracle’ as too obvious a connection to the Gospels’.

In any case, Suetonius’ linkage to Josephus’ ‘identification of the Christ’ passage to his ‘spit miracle’ is clear as he mentions Josephus and his ‘Christ prophecy’ of the Flavians:

“one of his high-born prisoners, Josephus by name, as he was being put in chains, declared most confidently that he would soon be released by the same man, who would then, however, be emperor.” “There had spread over all the Orient an old and established belief, that it was fated at that time for men coming from Judaea to rule the world. This prediction, referring to the emperor of Rome, as afterwards appeared from the event, the people of Judaea took to themselves;” Suetonius, Vespasian

Next, Suetonius provides the ‘secret’ basis for what the blind man the Jesus cured first saw – “trees like men walking”. The passage shows that – far from having blurred vision – Jesus enabled the man to see the truth; the Flavians Christs ‘messianic trees’.

“On the suburban estate of the Flavii an old oak tree, which was sacred to Mars, on each of the three occasions when Vespasia was delivered suddenly put forth a branch from its trunk, obvious indications of the destiny of each child. The first was slender and quickly withered, and so too the girl that was born died within the year; the second was very strong and long and portended great success, but the third was the image of a tree. Therefore their father Sabinus announced to his mother that a grandson had been born to her would be a Caesar.” Suetonius, Vespasian

Suetonius next shows he understands the Gospels precisely as he describes Vespasian as lacking a “certain divinity as a new made emperor”, which of course relates to its parallel in the Gospels of the “new made god” Jesus Christ :

“Vespasian as yet lacked prestige and a certain divinity, so to speak, since he was an unexpected and still new-made emperor; but these also were given him. he was at last prevailed upon by his friends and tried both things in public before a large crowd; and with success.

Suetonius then comes to the typological event that Jesus’s ‘spit miracle’ foresaw, which was Vespasian’s performance of the same miracle.

“A man of the people who was blind, and another who was lame, came to him together as he sat on the tribunal, begging for the help for their disorders which Serapis had promised in a dream; for the god declared that Vespasian would restore the eyes, if he would spit upon them, and give strength to the leg, if he would deign to touch it with his heel. Though he had hardly any faith that this could possibly succeed, and therefore shrank even from making the attempt, “

– which was the basis for the ‘typological prophecy’ in Mark 8: 24-25.

“So He took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the town. And when He had spit on his eyes and put His hands on him, He asked him if he saw anything. Then He put His hands on his eyes again and made him look up. And he was restored and saw everyone clearly.”

Note that though Vespasian mentions Serapis in his dream. Serapis was the equivalent of the Christ to the Flavians. He was simply an invented god they used as a mask to mystify hoi polloi. For example, Hadrian’s letter: “The worshippers of Serapis are called Christians and those who are devoted to the god Serapis call themselves Bishops of Christ.” Hadrian to Servanius 134 CE.

The conclusion of Mark’s Christ identification passage describes a binding and loosing.

So they said, “Some [say] John the Baptist, some Elijah, and others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.”

He said to them, “But who do you say that I am?”

Simon Peter answered and said, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.”

Then Jesus answered and said. . .

. . . “And I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” Matt 16:14-19

This foresees the Flavians ‘binding and then loosening’ Josephus described at the conclusion of the ‘Christ identification’ chapter.

“O father, it is but just that the scandal [of a prisoner] should be taken off Josephus, together with his iron chain. For if we do not barely loose his bonds, but cut them to pieces, he will be like a man that had never been bound at all.” Wars, 4, 10, 628-629

In other words, the Flavians gave to Josephus the same power that Jesus gave to his disciples. The purpose for this is obvious, what Josephus ‘bound’ – the fact that the Flavians are the Christ – will be bound in heaven and on earth. Josephus is wryly described as a “person of credit as to futuries”

If you strip away all the complexity what ones gets is this; the Flavian court historians identified the Flavian Caesar as the Christ. They also claimed that at this time Vespasian restored a man’s sight through his spit and experienced a binding and loosening event. At the point Jesus was identified as the Christ he restored sight with his spit and also described a binding and loosening.

The typological information was placed in different books to make the ‘secret’ connections more difficult to see. To show exactly why the typological passages were placed in different books I have assembled below how the actual passages appear side by side. As a collection the parallelism is too vivid to be overlooked.

“they brought a blind man to Him, and begged Him to touch him. And when He had spit on his eyes and put His hands on him, He asked him if he saw anything.” Jesus

“A man of the people who was blind came to him begging for the help ,,,that Vespasian would restore the eyes, if he would spit upon them, Vespasian

“Then He put [His] hands on his eyes again and made him look up. And he was restored and saw everyone clearly.” Jesus

“Though he had hardly any faith that this could possibly succeed, and therefore shrank even from making the attempt, he was at last prevailed upon by his friends and tried both things in public before a large crowd; and with success.” Vespasian

“I see men like trees, walking.” Jesus

“On the suburban estate of the Flavii an old oak tree put forth a branch an indications of the destiny of each child. the third was the image of a tree. Sabinus announced that Vespasian would be a Caesar.” Vespasian

“Who do men say that I am?” You are the Christ.” Jesus

“in their sacred writings, one from their country should become governor of the habitable earth. The Jews took this prediction to belong to themselves in particular Now this oracle denoted Vespasian, who was appointed emperor in Judea. Vespasian

” For if we do not barely loose his bonds, but cut them to pieces, he will be like a man that had never been bound at all.” Jesus

“whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” Vespasian

It is self-evident that as a collection the parallelism is noticeable. And this was what the authors of the typology wished to avoid, and is why the various typological pieces were placed in different books. (This is also why there are three Synoptic Gospels.) The point of the hidden Jesus/Titus typology was to allow the canon to function as it did but with the possibility the typology would someday be noticed and give the Flavians what they wished – immortal legacy.

Notice that while is it certainly possible to contest each individual parallel as having been deliberately created, it is not possible to argue that the collection is not unusual. For example, each of the three parallels – ‘Christ identification’ spit miracle and ‘binding and loosening’ has been noticed by other scholars though no one ever realized that each group occurred at the same time.

Read CM and you will see that this pattern extends across all the Synoptics and Josephus.

Copywrited material, All Rights Reserved

Hope this is clarifying

Joe

I think the birth narratives of Matthew and Luke were written, at least in part to counter the adoptionist narrative which makers more sense. The one thing that the adoptionist narrative avoids is why Yahweh was so inept that He had to make a human being as a baby. He had a track record of creating full-fledged humans “in the beginning” as it were. So Jesus would have been made on one day and started his mission the next. Jesus family was superfluous to his message and none of his disciples knew of Him from before.

Why would 30+ years of time be allowed to pass as Jesus grew up, with people dying and going to Hell from ignorance of Jesus mission? So, as soon as Yahweh decides to trigger his plan, voila Jesus exists and starts his mission.

Actually, when you think about it, this is a fairly lame plan from an all-knowing, all-powerful entity. Why eliminate the teaching savior to one culture? Could not the effort run simultaneously around the Earth in all cultures. And then wouldn’t people be amazed at God’s power when they learned that a messenger was sent to all of these other cultures, bearing the good news, too? And that would eliminate any time lag for people in the Arctic having to wait for some enterprising preacher to reach them, this saving more people from hell for ignorance.

We seem to get overly focused upon the details and don’t stop to consider the “big picture.”