Richard Bauckham is not a mythicist. I have no doubt he would emphatically oppose the very idea. General readers probably know him best for his book Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony in which he argues the Gospel narratives were sourced from traditions guaranteed by eyewitnesses of Jesus. I happen to think that book was one of the worst pieces of nonsense I have ever read and suggested it might best be explained by issues related to an illness from which Bauckham was recovering at the time he wrote it. But when Bauckham is not attempting to do history he can be very interesting. So I’m thrilled to write something positive about a Bauckham book for a change.

God Crucified was first published in 1998 and reissued as a chapter in a larger volume, Jesus and the God of Israel, two years after Jesus and the Eyewitnesses. Bauckham argues that the New Testament consistently portrays Jesus as part of the Godhead itself. The earliest Christology was a “High Christology”. That is, views about Jesus did not gradually evolve from the time of “the resurrection appearances” through a series of graduating exaltations until he was eventually worshiped alongside, or as part of, God. He was identified with God by the earliest Christians before any of the New Testament was written.

This view of Jesus was derived from an interpretation of the passages in Isaiah where God is said to both reside in the highest places where he sits as supreme ruler over all creation, and also with the lowly on earth, in particular with the suffering Servant. God raises that suffering Servant from death to be with him in the highest places, too, thus identifying himself with that one who had been abased.

Bauckham believes that this view (that I address in more detail in this post) explains how the human Jesus came to be identified with ruler of the universe. I think Bauckham’s argument holds perfectly for “Christ crucified”, but runs into problems when one tries to relate it to a pre-crucified human Jesus. I wonder if his argument better supports mythicist scenarios that argue Jesus was initially a figure who only took on flesh or a form of flesh for the short time necessary to be crucified.

Understanding Early Jewish Monotheism

Bauckham begins by setting out the two main scholarly views of Second Temple Jewish monotheism:

- Those who believe Second Temple Jews at the time of Jesus were “strict monotheists”; Jesus in New Testament times thus could never have been considered really divine. Such a development must have taken place later and involved a complete break from Judaism.

- Those who think of Jewish monotheistic views were blurred by the roles of intermediary figures such as exalted angels and humans, and personified divine attributes like Wisdom, who were ambiguous semi-divine figures; Jesus’ exaltation to divine status happened in this context, so that he was initially seen as another type of principal angel or divine human in God’s presence.

Bauckham believes the discussion has been hampered by a failure to work from a clear definition or set of criteria to clarify what was meant by “God” or “the divine” among Jews of the time. The mistake has been made in trying to define the Jewish idea of God in (Hellenistic) terms of “the nature of God”. Rather, the Jews identified themselves as monotheists, and thus different from other peoples and religions, by appealing to the identity of their God, not its nature.

To the Jews God identified himself as YHWH and the one who was abundant in love and reliability. This same God was contrasted with the gods of the heathen, however, by being the Creator of everything and the Ruler of everything. The Jews thought of their God as unique in the world because of these twin attributes: the sole Creator and the sole Ruler of all things.

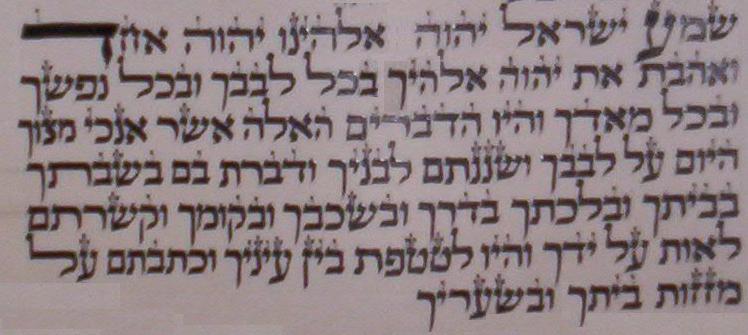

Bauckham writes that “there is every reason to suppose that observant Jews of the late Second Temple period were highly self-conscious monotheists. Their worship practices included the daily recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4-6) and the Decalogue — both of which utter reminders of God being One God.

Jewish mediator figures are irrelevant

Now if we understand this Jewish identification of God as being the Supreme Ruler and Only Creator of the universe, then the argument that other intermediary figures of the time were somehow “almost God” or in some half-way staging post towards becoming a/the God being themselves collapses. No matter how exalted are the heavenly Abraham and heavenly Adam, they can never be identified as Creator of all things. The exalted angels never sit with God on his throne. They always stand, the posture of servants. Worship was always restricted to God alone:

However diverse Judaism may have been in many other respects, this was common: only the God of Israel is worthy of worship because he is sole Creator of all things and sole Ruler of all things. Other beings who might otherwise be thought divine are by these criteria God’s creatures and subjects. (p. 9, Jesus and the God of Israel)

One exception

But there is one exception that will become a focus of future posts here:

There is one exception which proves the rule. In the Parables of Enoch, the Son of Man will in the future, at the eschatological day of judgement, be placed by God on God’s own throne to exercise judgement on God’s behalf. He will also be worshipped. Here we have a sole example on an angelic figure or exalted patriarch who has been included in the divine identity: he participates in the unique divine sovereignty and, therefore in recognition of his exercise of the divine sovereignty he receives worship. . . . (p. 16)

Bauckham footnotes a reference to “a second case . . . frequently alleged” where a patriarch is exalted to the divine status of taking his place on God’s throne: Moses in the Exagoge of Ezekiel the Tragedian. Bauckham believes the scene where Moses has a dream of God vacating his throne for him has often been misinterpreted: the dream is a metaphor for Moses’ earthly role as ruler of Israel.

Personification or hypostasis of God’s attributes

Second Temple literature also testifies to the Wisdom and Word of God having separate existences from God himself. There is a question of whether the literature is merely speaking of these as metaphors (personifications) or whether the author really thought of them as having separate “bodily” realities. Bauckham sees a good argument for the latter view in some of the texts about Wisdom.

Whatever the case, monotheism is not compromised by these figures since they are not considered to be subordinate divinities, but represent distinctions between different aspects of the one God.

Bauckham makes no reference to the Elephantine texts from the fourth century BCE that inform us some Jews worshiped other gods alongside Yahweh. He is clear that he is talking about “late” Second Temple times. But one must always wonder how secure such a theory is given that until the discovery of the Elephantine texts scholars had no reason to doubt that even in the “early” Second Temple era Jews were typically “strict monotheists”.

Christological Monotheism in the New Testament

Bauckham argues

what will be seen to anyone familiar with the study of New Testament Christology a surprising thesis: that the highest possible Christology — the inclusion of Jesus in the unique divine identity — was central to the faith of the early church even before any of the New Testament writings were written, since it occurs in all of them. (p. 19)

This view of Jesus did not require any compromise with existing Jewish faith, says Bauckham. Early Christians

saw in this inclusion of Jesus in the divine identity the fulfilment of the eschatological expectation of Jewish monotheism that the one God will be universally acknowledged as such in his universal rule over all things. . . (p. 19)

I think Bauckham is right when he points out that arguments that Jesus was somehow gradually elevated to a divine status by degrees over time makes no sense:

Though such a step was unprecedented, the character of Jewish monotheism did not make it impossible. Moreover, it was not a step which could be, as it were, approached gradually by means of ascending christological beliefs. To put Jesus in the position, for example, of a very high ranking angelic servant of God would not be to come closer to a further step of assimilating him to God, because the absolute distinction between God and all other reality would still have to be crossed. The decisive step of including Jesus in the unique identity of God was not a step that could be facilitated by prior, less radical steps. It was a step which, whenever it was taken, had to be taken simply for its own sake and de novo. It does not become any more intelligible by being placed at the end of a long process of christological development. (p. 20)

Bauckham’s second part of his book demonstrates that Jesus throughout the New Testament is, indeed, identified with God.

Sovereign over all things

The most quoted Old Testament text in the New Testament is Psalm 110:1

The LORD says to my Lord: “Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.”

Christians, unlike other Second Temple Jews, interpreted this to mean that God placed Jesus on the divine throne itself, thus claiming that Jesus participated in God’s “unique divine sovereignty over all things.” Sometimes, to reinforce the point, they associated it with Psalm 8:6 as in Matt. 22:44; Mark 12:36; 1 Cor. 15:25-28; Eph. 1:20-22; 1 Pet. 3:22; cf Heb. 1:13-2:9

You made him ruler over the works of your hands; you put everything under his feet.

(I have hyperlinked the above texts so you can assess for yourself Bauckham’s claim that these verses associate the two Psalms. Some do; I don’t see this in Matthew or Mark, though.)

Bauckham’s argument is that

the exaltation of Jesus to the heavenly throne of God could only mean, for the early Christians who were Jewish monotheists, his inclusion in the unique identity of God, and that, furthermore, the texts show their full awareness of that and quite deliberately use the rhetoric and conceptuality of Jewish monotheism to make this inclusion unequivocal. (p. 23)

Above all angels

Ephesians 1:20-21

[God] raised Him from the dead and seated Him at His right hand in the heavenly place, far above all principality and power and might and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this age but also in that which is to come. And He put all things under His feet.

“The point is”, says Bauckham,

that Jesus now shares precisely God’s exaltation and sovereignty over every angelic power. (p. 24)

The same is found in Hebrews 1.

Given the divine name

Bauckham dares to say what probably most readers only quietly wonder about: Philippians 2:9 says Jesus is given “the name above every name” by God when he is exalted to the highest position in heaven. The early Christian confession and Old Testament phrase “to call upon the name of the Lord” was an invocation of the name of God. Jews knew that name as YHWH. The early Christians applied that name to Jesus.

Philippians 2:9

Therefore God also has highly exalted Him and given Him the name which is above every name

Early Christians invoked Jesus as the divine Lord who exercises divine sovereignty and bears the divine name.

Jesus was worshiped as the unique divine ruler

If Jesus was worshiped it was, says Bauckham,

due to Christ precisely as response to his inclusion in the unique divine identity through exaltation to the throne of God. (p. 25)

Philippians 2:9-11 is a speaks of the entire world worshiping Christ (Bauckham dismisses those arguments that say this passage is about a divine Adam) and Revelation 5 likewise shows worship of Jesus. Matthew 28:17 also is significant. It depicts the disciples worshiping Jesus in the context of him being given all authority in heaven and earth.

The pre-existent Christ as creator

The way Bauckham phrases this is to say Jesus “participates in God’s unique activity of creation”. Jesus “work in creation” is found in 1 Corinthians, Colossians, Hebrews, Revelation and the Gospel of John.

Bauckham dwells upon 1 Corinthians 8:6, showing that Paul has here borrowed from the Jewish ritual confession that God is One God (the Shema: Deut. 6:4) to apply it to Jesus as the “one Lord”:

Therefore concerning the eating of things offered to idols, we know that an idol is nothing in the world, and that there is no other God but one.For even if there are so-called gods, whether in heaven or on earth (as there are many gods and many lords),

yet for us there is one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and we for Him; and one Lord Jesus Christ, through whom are all things, and through whom we live.

If Paul “were merely associating Jesus with the unique God he certainly would be repudiating monotheism”, but from the context of stressing the “one-ness” of God, and using the Shema for this purpose, Bauckham’s argument is that Paul is “including Jesus in this unique identity” of the one God.

Throughout the New Testament we see Christ identified with the Wisdom of God, with the Word of God, and participating from the beginning in the Creation of all things.

God Crucified: The Divine Identity Revealed in Jesus

So how did it all get to be this way? As I read all the above by Bauckham I am constantly reminded of mythicist arguments and all the historicist counter-arguments that fly in the face of everything Bauckham has written. But some of those most dismissive of mythicism (e.g. Larry Hurtado) find Bauckham’s case in large measure valid. Mythicist Earl Doherty, in responding to Bart Ehrman, points out that many historicists have a poorly informed understanding of how early Jews could have conceived of Jesus as divine. Indeed, it appears that Paul’s concept of the divine Jesus was of some kind of emanation of God as opposed to a distinct being that would have violated Jewish monotheism. That sounds to me something like the concept Bauckham is proposing.

So I can understand how this view of Jesus being identified with God certainly sits well in a mythicist scenario, but Bauckham must apply it to the earthly Jesus. I find Bauckham’s reasoning plausible right up to where he himself stops short: applying God-identification to a preaching and healing (or any type of pre-crucifixion) career of Jesus.

The influence of Isaiah 40-55

These chapters (known to scholars as Deutero-Isaiah) were among the most important for early Christians. The very word “gospel” comes from Isaiah 40:9. (Crossan infers that it comes from Roman imperial propaganda.)

The beginning of the Gospel with the preaching of John the Baptist and the theme of the New Exodus are all found in Isaiah 40:3-4.

Bauckham says that scholars have generally failed to appreciate that behind many New Testament texts lies an integrated reading of these chapters from Isaiah. We may notice Isaiah 53 and the Suffering Servant being used in the NT, but Bauckham wants us to notice that this passage does not stand alone in the views of the authors. It is part of a larger whole: 40-55.

Now there is a Jewish principle of interpretation that holds that passages in which the same word occurs should be interpreted with reference to each other. (Bauckham does not explain how he knows that this principle was employed by Jews before rabbinic Judaism, but I did earlier discuss the same exegetical technique in relation to Paul’s interpretation of “seed” in Genesis as a “messiah text”, so let’s continue.) So see what happens when we place side-by-side the following three passages from Isaiah:

Isaiah 52:13 (LXX) Behold, my Servant shall understand, and shall be exalted (hupsothesetai) and shall be glorified (doxathesetai) greatly.

(Heb): Behold, my Servant shall prosper; he shall be exalted (yarum) and lifted up (nissa) and shall be very high (gavah).Isaiah 6:1 (LXX) I saw the Lord sitting on a throne, exalted (hupselou) and lifted up (epermenou); and the house was full of his glory.

(Heb): I saw the Lord (adonai) sitting on a throne, exalted (ram) and lofty (nissa); and his train filled the temple.Isaiah 57:15 (LXX) Thus says the Lord Most High (hupsistos) who dwells in the heights (en hupsetois) forever, Holy among the holy ones (en hagiois) is his name, the Lord Most High (hupsistos) resting among the holy ones (en hagiois), and giving patience to the faint-hearted, and giving life to the broken-hearted.

(Heb): For thus says the exalted (ram) and lofty (nissa) One who inhabits eternity, whose name is Holy: ‘I dwell in the high (marom) and holy place, and also with those who are crushed (dakka; cf. Isa. 53:5, 10) and lowly in spirit, to revive the spirit of the lowly and to revive the heart of the crushed.’

The Servant in Isaiah 52:13 is “exalted” and “lifted up”. The same words are used to describe God being exalted and lifted up, or dwelling in the heights.

The verbal coincidence between these three verses is striking. Modern Old Testament scholars think the two later passages, Isaiah 52:13 and 57:15, must be dependent on Isaiah 6:1. Early Christians would have observed the coincidence and applied the Jewish exegetical principle . . . according to which passages in which the same words occur should be interpreted with reference to each other. (p. 36)

So the Servant of Isaiah 53:13 is, in the light of Isaiah 6 and 57,

exalted to the heavenly throne of God.

(Compare John 12:38-41 which brings Isaiah 53 and Isaiah 6 together to claim Isaiah saw the glory of Jesus.)

And if the Servant is exalted to the throne of God, then he is readily linked with Psalm 110:1, shown above to be one of the most popular of Christian texts and one that early Christians used to identify Jesus with God.

God, we learn, not only dwells in the Most High places, but he also dwells with those who are lowly and broken.

When the nations turn to acknowledge this God, it is the Servant, once humiliated and now exalted, whom they acknowledge.

Bauckham next shows in detail that

- the Philippian Hymn (Phil. 2:6-11) appears to draw upon Isaiah 45:22-23;

- the Book of Revelation gives Christ titles (Alpha and Omega, First and Last) borrowed from Isaiah 44 and 48;

- the seven “I am” or “I am he” identifications of Jesus in the Gospel of John correspond to the seven “I am” counterparts in the Hebrew Bible, six of which are in Isaiah.

I will skip the detailed arguments for now. Maybe I will return to some of them later. The point is that all three of these passages together are drawing upon the same Isaiah passages to clearly identify “the crucified Jesus as belonging to the identity of God” (p. 50).

He is exalted above all only as the one who is also with the lowest of the low. This is the meaning of the therefore of Philippians 2 (because Jesus degraded himself to the lowest position, therefore he was exalted to the highest position). This is the meaning of the slaughtered Lamb’s standing as slaughtered on the heavenly throne of God in Revelation 5. This is the meaning of the Johannine paradox that Jesus is exalted and glorified on the cross. (p. 51)

He emphasizes three points here:

- It may seem bizarre that the Most High God could be identified with the lowest, but this is already part of what the Jewish scriptures declare: Isaiah 57:15 says that the Most High God “dwells also” with the lowly and crushed.

- The Prologue of the Gospel of John builds upon the scene of Moses not seeing but only hearing God declare that he is full of “steadfast love and faithfulness”. In the life of Jesus God reveals himself as the one full of grace and truth. This, and the preceding point, are novel, but they are not uncharacteristic of the Jewish God.

- Just as God had to reveal his new name and identity in YHWH in order to lead Israel out of Egypt, so God reveals himself anew in Jesus. (Bauckham is possibly thinking of the Second Exodus here.) At the same time God must once again disclose a new identity — the one found in Matthew 28:19, “the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit”, which “names the newly disclosed identity of God” (p. 57). God is thus identified from the Gospel narrative as “Father, Son and Holy Spirit” (p. 59).

Bauckham concludes by pointing to the two points he has been arguing:

(1) New Testament writers clearly and deliberately include Jesus in the unique identity of the God of Israel;

(2) The inclusion of the human life and shameful death, as well as the exaltation of Jesus, in the divine identity reveals the divine identity — who God is — in a new way. (p. 57, my formatting)

I can follow Bauckham’s argument as it applies to Christ crucified. I can see how the metaphor for Israel in the Servant Songs of Isaiah came to be identified with a single figure. But Isaiah 53, the portrayal of the Suffering Servant, is about a man in a state (not a linear life) of suffering and rejection. If God is dwelling with the lowly and crushed as he also dwells in the highest, then we have a God who is presenting himself at two extremes: highest glory and lowest shame; ultimate power and utter abasement.

The question must arise: How could the life of a man known to have lived a life of ups and downs, indeed many “ups”, be identified with this figure? Did not Jesus, whether rabbi or revolutionary, attract large crowds, win a large measure of fame and popularity, regularly get the better of his opponents in verbal confrontations, lead others to forsake all and follow him, inspire rumours that he had performed fantastic feats? This is not the Suffering Servant of Isaiah.

Now I can understand how an evangelist, say Mark, would write a parable or a metaphorical story about God in the flesh, and how this story would present Jesus as simply too incomprehensible and majestic to be comprehended by any mortal with whom he came in contact. His words would be mysteries (parables), his power would be beyond comprehension. No matter how often he commanded his identity be kept quiet until after the resurrection, his works would be so astonishing that such commands were generally useless — and only added to the confusion and mystery. Details of such a life would no doubt be stitched together from other Scripture stories, like those of Elijah and Elisha, Moses and Joshua. They would make no sense as literal history or biography. But all of this would have been an afterthought in order to flesh out a parabolic narrative around Christ Crucified. And it would be in the scene of the crucified Christ that we would read the rich heritage of all the theologizing from scriptures that had gone into the manufacture of the Suffering Servant at his point of rejection and death. Every line would be an allusion to scripture.

The Suffering Servant, the Crucified Christ, came first. He was identified with God from the beginning because he was found in the same Scriptural source that spoke of God. If this was consistent with Jewish monotheistic beliefs, and Bauckham makes a case that it was, then one can imagine some others being persuaded. We might wonder if the abasement took place in the lower heavens with Jesus in the form of flesh, or if Jesus actually suffered for a while on earth, but in either place it was at the hand of the demons, as Paul indicates was the original belief.

Later an earthly life was added, first as a metaphor or theological parable.

But try to imagine a real-life, a known personality, being taken up and interpreted through these passages. Only the most fanatically loyal followers would be convinced. How could Jews in Jerusalem who supposedly rejected this figure and ensured he died as a criminal ever be convinced?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

There are two huge assumptions driving Bauckham’s arguments.

1. (Late) Second Temple Jews were “strict monotheists.” There were no exceptions.

2. “Early Christians” were Palestinian Jews.

You’ve already demonstrated how assumption #1 is untenable. Scholarship merely assumed Jews were always “strict monotheists” until the archaeological excavations of the 20th Century proved them wrong. “The Parables of Enoch” show that some Jews were willing to engage in theological speculations about a mysterious “Son of Man” (not “Messiah”) who would sit on the right hand of God. So, this isn’t monotheism.

And, of course, the only evidence we have that early Christianity even started among Jews in Palestine are fictional revisionist documents like Acts and the Pauline Epistles. All written in Greek, all with a heavily anti-Jewish bias, nothing which betrays a Palestinian Jewish origin.

We can neither assume that all Jews were “strict monotheists,” nor that early Christians were Palestinian Jews, or Jews, period. An interest in Jewish scripture does not automatically betray Jewish authorship — particularly not when such authors are doing everything they can to distance themselves from Jews.

“Jew” is an interesting term. It’s not unlike “Israel” which can have a range of meanings. See Where Did the Bible’s Jews Come From? Part 1 and Part 2.

Larry Hurtado has strong views about the place of Enoch in all of this, and I look forward to addressing his views along with others in future posts on Enoch.