The influences of Mesopotamian creation stories in Genesis are clear. But how those stories came to be re-written for the Bible is less clear. Russell E. Gmirkin sets out two possibilities in Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch:

The traditional Documentary Hypothesis view:

Around 1400 BCE the well-known Babylonian Epic of Creation, Enûm Elish, the Epic of Gilgamesh and other stories found their way through Syria and into the Levant where the Canaanites preserved them as oral traditions for centuries until the Israelites learned of them. Then around the tenth or ninth centuries these Israelites incorporated some of those myths into an early version of Genesis (known as J in the Documentary Hypothesis).

About four centuries later, around the fifth century, the authors of that layer of the Bible known as P took quite independently orally preserved overlapping Mesopotamian legends and used them to add additional details from those myths that had been preserved by the Jews orally throughout to the J stories.

Now one remarkable aspect of this scenario (accounting for the Mesopotamian legends underlying Genesis 1-11) that has been pointed out by Russell Gmirkin is that though they had been preserved orally for centuries by the Canaanites, in Genesis they are completely free from any evidence of Canaanite accretions. This should be a worry, says Gmirkin, because Canaanite influences are found throughout the rest of the Bible.

Gmirkin suggests that this traditional model of how the Babylonian legends came to be adapted in the Genesis narrative is strained, so he proposes an alternative.

The author/s of Genesis 1-11 borrowed directly from the early third century (278 BCE) Babyloniaca of the Babylonian priest Berossus. The sources for this work show that Berossus himself drew upon the Babylonian epics of Creation and Gilgamesh, and Gmirkin argues that some of his additions and interpretations found their way into Genesis. Moreover, the Epic of Creation that resonates in Genesis, the Enûm Elish, was quite unlike other Babylonian creation myths:

- the standard Babylonian myth of creation (e.g. Atrahasis Epic, Enki and Ninmeh) began with earth, not with waters;

- Enûm Elish was specifically associated with the cult of Marduk, localized in Babylon — its purpose was to explain why the Babylonian patron god, Marduk, had been promoted over the other gods.

Note also:

- during the late Babylonian period and Seleucid times, the Enûm Elish likely increased in significance, but was still only recited in Babylon’s New Year Festival;

- Berossus was himself a priest of Bel-Marduk in Babylon at this period. For Berossus, the Enûm Elish would have been the definitive creation epic.

The Enûm Elish was very likely unknown beyond the region of Babylonia until Berossus himself drew attention to its narrative for his wider Greek audience. Gmirkin believes the simplest explanation for the Enûm Elish’s traces in Genesis is that they were relayed through Berossus’s Babyloniaca.

Here is a table comparing the details of the Genesis Creation with those found in the Babylonian Creation Epic and in Berossus’s third-century work:

|

Genesis |

Enûma Elish |

Berossus |

| Opening words: In the beginning God created the heavens (sky) and the earth | Preface to Babyloniaca informed readers it contained the histories of the sky, the earth and the sea, of creation, and of kings and their deeds | |

| Heavens and earth “were begotten” | The word in Berossus for creation is literally “first birth”. Berosses also called his first book “Genesis” or “Creation” (Procreatio) | |

| Creation is a series of separations | Creation is a series of separations | |

| Primal watery chaos | Primary watery chaos – Apsu, fresh waters; Tiamat, the saltwater ocean; Mummu, mist or clouds. | Primary watery chaos – Apsu, fresh waters; Tiamat, the saltwater ocean, explicitly equating Tiamat (Thalatth) with the sea (Thalassa); Mummu, mist or clouds. |

| Darkness was upon the face of the deep | Primordial universe consisted of nothing but waters (no darkness is mentioned) | Primordial universe consisted of nothing but “darkness and water” – Berossus equated Tiamat with the Moon (Selene), known as “the ruler of the night”, and whom he also equated with a flood goddess, Omorka. |

| God divided the light from the darkness | Bel (i.e. Marduk, the sun god) “cut through the darkness and separated the sky and the earth” | |

| Light existed prior to the creation of the heavenly luminaries. God created light | Light existed prior to the creation of the heavenly luminaries. Light emanated from Marduk | Light existed prior to the creation of the heavenly luminaries. Light emanated from Bel (=Marduk) |

| First act of creation was division of waters above from waters below to create a firmament/sky | First act of creation was division of waters above from waters below to create a firmament/sky | First act of creation was division of waters above from waters below to create a firmament/sky |

| Dry land was then created | Dry land was then created | Dry land was then created |

| Then the luminaries were created | Then the luminaries were created | Then the humans were created |

| Then the humans were created | Then the humans were created | Then the luminaries were created. (The order is reversed here, but Gmirkin points out that we rely on the abridged excerpts of Berossus by Alexander Polyhistor here and the order may have been reversed.) |

| Animals were created | Animals were created | |

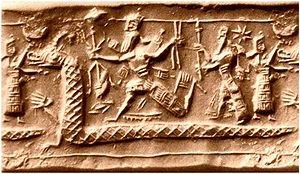

| All created animals reproduced “after its own kind” – this is repeated, thus a polemic against the Mesopotamian tradition? | Earliest animals included monsters of a composite nature: man-birds; man-goats; man-fish; man-horses; dog-horses; and many others | Earliest animals included monsters of a composite nature: man-birds; man-goats; man-fish; man-horses; dog-horses; and many others |

| God rested from his labours on the seventh day. | Marduk created humans to do the hard work so as to give the gods a life of leisure. | In the Atrahasis Epic (likely known to Berossus), after the universe was created, the gods had to do all the manual labour, digging canals, raising crops, so that they were ready to rebel. Enki therefore created humans to do the work. |

I know, I need to quote passages attributed to Berossus to flesh the above out somewhat. But I’m taking short-cuts for now since I’m traveling. Maybe next time.

I am interested in comparing the arguments of Russell Gmirkin with those of Philippe Wajdenbaum who argues for the influence of Plato on Genesis. That will be for future posts. (Compare also Lukas Niesiolowski-Spano.)

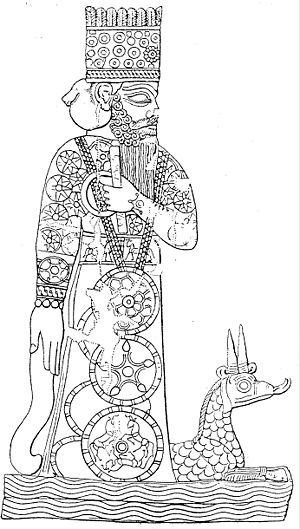

Another detail I’ll post on soon is Gmirkin’s suggestion that the Serpent in the Garden of Eden was drawn from the half-fish and half-man Oannes of Babylonian myth.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The ‘lack of Canaanite accretions’ argument is a good one for an author Genesis directly borrowing from Mesopotamian traditions. However, I don’t see more evidence for a Hellenistic-era borrowing than for an Exilic-era one as suggested by Walter Mattfeld (at bibleorigins.net).

It comes down to the best way to account for specific details in common to both Genesis and Berossus, other more recent arguments for a Hellenistic dating of the Pentateuch/Primary History, and the evidence extant that supports the scenario of the sort of literary activity during the Babylonian Exile that an Exilic provenance assumes.

Philip Davies, for one, considers the notion of a revivalist theological-literary activity during the Babylonian captivity to be quite romantic and fanciful.

If theological-literary activity in impoverished Persian-era Yehud is not romantic or fanciful, why should such activity in Neo-Babylonian Babylonia be considered romantic and fanciful?

The evidence for the infrastructure/economic/demographic conditions necessary to support such literary activity, along with the conditions supporting the ideological themes of the literature of the Bible, are arguably well established in the Hellenistic era, which is the period of literary activity argued by Grimkin. I have skirted around this in earlier posts, and it’s one I would love to take the time to do more thoroughly. (The ideological conditions required for the themes throughout the Primary History/Pentateuch are certainly present in the Persian era.)

I thought I had begun to post more details on this context only last year — but turns out it was 2009: http://vridar.wordpress.com/2009/11/15/origins-of-the-israel-of-the-bibles-narrative-1/ — must complete this soon!

As for the Babylonian Exile being problematic as a provenance of a literary revival, see Event 1 at http://vridar.info/bibarch/arch/davies3.htm

According to 2 Kings 17:30, deportees were allowed to continue their religious practices in the lands they were deported to. After a few generations, however, intermarriage would destroy any sense of the deportees’ original identity (as it did in the case of the Israelite deportees in 720 BC and in the case of the deportees mentioned in 2 Kings 17:30). Besides, there is clearly pre-Exilic material in the Primary History, strongly suggesting the Judahite deportees to Babylonia did continue to preserve the written material they brought with them.

Is 2 Kings 17:30 reliable history or is it an eponymous tale to “explain” and denigrate the different religious practices of the Samaritans?

Certainly there are a few names of pre-exilic kings in the Primary History, but rarely, if ever, do the settings of these kings in this History coincide with the information about them in the external archaeological evidence, iirc.

Did the names of these pre-exilic kings appear in the History after being preserved through records carried with the deportees to their exile and back again, or were they found in the archives that had been left behind and remained in the conquered lands for the benefit of the new administrators? (Is it likely that people being deported would have been allowed to bring with them their administrative records and archives?)

We have evidence from other deportations that sometimes deportees were being resettled and told that they were returning to lands of their ancestors and were required to restore the worship of the gods of that land. The deportees were told they were being liberated, and they would have had an interest in believing that they were being chosen by the imperial powers and higher gods to re-inhabit a land in which they found themselves strangers — among “nonbelieving” “people of the land” who assumed the position of being the poor, the dispossessed, the servants of the imperially backed new occupiers.

http://vridar.wordpress.com/2009/11/15/origins-of-the-israel-of-the-bibles-narrative-1/

I was thinking more of the town lists in Joshua than of the king names, but those do just as well. There are some 42 names of pre-Exilic kings of Israel and Judah in the Primary History (most of whom are not externally attested), the first of whom is externally attested is Omri (or is it David?). I see no reason for pre-Exilic material of the kind we find in the Primary History to be preserved at Mizpah and some reason for this material to be preserved by the Judahite deportees to Babylonia. As for 2 Kings 17:30, there were certainly East Semitic deportees settled in Samaria by the Assyrians. The Samaritans’ culture, as detected from archaeology, was almost entirely not East Semitic. Can you give examples of these resettlements?

What I am questioning is the likelihood and possibility of any deportees of any kind taking with them into exile written annals of their kings. What is the reason you see for this material being preserved by “Judahite deportees to Babylonia”?

My comment on 2 Kings 17 was not to deny forced resettlement of Samaria, but to raise the question of the value of 2 Kings 17 as a historical source.

John Day also has an article about how the details of the Genesis flood story more closely those of Berossus than of the Enuma Elish.

Will do a few more from Grimkin and no doubt cover this aspect, too.

I have been taking Berossus into account a long time. I’m thinking we now know that Hesiod’s theogony (or the essence of it)went to Mesopotamia in the Enuma Elis.

Oannes being identified with the serpent in Eden may, or, may not be correct. Though, I believe the serpent is Enki’s agent, or, protege, as Oannes was. John the Baptist is the one “keeping wisdom in the world” as Enki’s protégé in Mark’s gospel. We are actually seeing the folkloric “companion”, which became the animal helper, whereby the hero obtains help. That’s why Enkidu is “the strong comrade who sends help in time of need”, Eve is a “help meet” for Adam, and, Lazarus means “God has helped”. Lazarus is the one (and only ever) guy who actually did have a personal relationship with Jesus.

The fish can be an equivalent symbol to the serpent, however.

I am working on my book, Magic Jesus.

Price went about as far as to say Berossus wrote parts of Genesis.

You might actually identify John The Baptist with Leviathan as easily as with Ea/Enki, as with Oannes.

Would you like to elaborate on your comment?

John The Baptist is a hero character bearing the traits of the river serpent so ubiquitous the Hebrew Bible (Leviathan, Rahab, Tiamat/Tohu), and echoes the cursed Nuhushtan. Whether he is the protege of Enki, Leviathan, or other serpent/river god is somewhat beside the point. But, I would choose the Enki myth. Like Enki/Ea, John is the water bearer (camel hair), but reflects the curse of autochthonous spirits throughout mythology, the funny walk.

The serpent in the garden is cursed to go on his belly and eat the dust of the ground, as rivers do, because it represents the river deity. These heroes are associated with the craft gods, tektons like Oannes.Oannes wears the Apkallu fish costume, John the camel hair, bearing the water, (Ea IS Aquarius). Echoing John’s role is “Kyrene”, Simon (Shimeon-moon god) Of Kyrene’s title names the goddess, Kyrene, who is a woman in a man’s role, as John is a man in a woman’s role.

She is the same as John (but for Greek girls), the priest/priestess of the initiation into adulthood, which is circumcision/marriage/coming of age . John is a male birther, Kyrene, a female warrior.

Oannes wears the Apkallu fish costume, John the camel hair, bearing the water (Ea IS Aquarius) through the wilderness. Moreover, Kyrene is a twin, a favorite device of Mark. She is “The Second Artemis”.

Circumcision was originally the coming of age ritual. John embodies the circumcision and baptism, essentially equating the rituals, and potentially even ending the circumcision requirement as Jesus ends the blood sacrifice requirement.

More about marriage later- Magic Jesus, And The Wizards Of God (book project).

Pardon the poor edit above.

Moreover, as Price shows, Genesis is like Zeus flicking Hephaestus off Olympus, the serpent being cursed to lose his legs, the etiological myth which explains serpents having vestigial legs. Oedipus, another lame autochthonous hero, lends his hero power to Athens. John lends his to Jerusalem/Israel.

But, the curse of Yahweh upon the seed of the serpent and the seed of Eve is an allegory for circumcision and deflowering, the bruised or wounded serpent heads (foreskins) and serpent heels (hymens). The woman is typically reborn on her wedding night, the man at circumcision, now at baptism.

I’m saying we’re reading allegorized ritual.

Hercules wrestles the hydra, the original Greek Leviathan, and channels rivers to clean the Augean stables. It has to do with extensive instrumental use of water by urban areas, whereby the water spirits are demonized. You have the same thing in the combat myths of Mesopoatamia, which Genesis is a variant of.

Leviathan, Lotan, Ea/Enki, Rahab, Nehustan, all versions of the river god. And, “Peniel” in Genesis is Greek “Peneus”, the river god, FATHER OF KYRENE.

Philip– what you have given are allegorical interpretations. What interests me is something else. I am looking at literal connections and sources.

The World of Berossos

Johannes Haubold, Giovanni B. Lanfranchi, Robert Rollinger, John M. Steele, The World of Berossos: Proceedings of the 4th International Colloquium on “The Ancient Near East between Classical and Ancient Oriental Traditions”, Hatfield College, Durham 7th-9th July 2010. Classica et Orientalia, 5. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2013. vii, pp. 332. ISBN 9783447067287 Table of Contents: https://d-nb.info/1026220297/04

Book Review: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2014/2014.05.50/