Would the Gospels be any more credible if their authors clearly left their names in them, along with a little biographical information clearly linking them to known historical persons, and if they at every point in their narrative informed readers of their sources for each set of sayings by Jesus and for each incident? Some sources they would explain were oral witnesses, some were official documents, maybe even some inscriptions that could be verified by any person in the region in their day.

Supposed a critic still dismissed them as fabricated tales. Would we be outraged that such a critic was completely biased against the Gospels and that she would never be so sceptical of secular writings with such an abundance of confirming testimony?

The answer ought to be that “it all depends”. It all depends on a critical analysis of all of that information. That would not be being biased against the Gospels. It would be treating the Gospels in exactly the same way scholars worth their salt treat their secular sources.

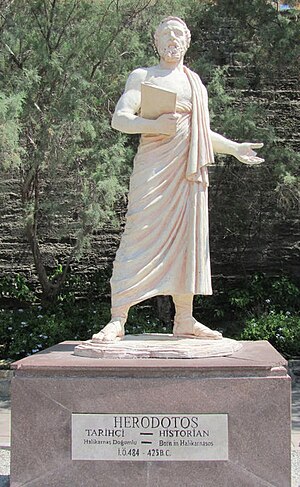

Take studies of Histories by Herodotus for instance. Herodotus has long been considered an essential source for our knowledge of the ancient world. By his own testimony he traveled widely, examining cultures first hand and gathering information from a wide range of sources, oral and written. Sure some of his tales are clearly fabulous, but why should we doubt that even those have some historical core in many cases?

1989 saw the English translation of Detlev Fehling‘s Herodotus and His ‘Sources’: Citation, Invention and Narrative Art, originally published in German in 1971. I will post from time to time on aspects of this book but for now let me outline his main arguments as summarized by Katherine Stott in Why Did They Write This Way? Reflections on References to Written Documents in the Hebrew Bible and Ancient Literature (2008):

Fehling expresses strong reservations about the picture that Herodotus paints of his investigative procedures and argues that his source designations cannot be taken as genuine. He suggests that Herodotus’ citations follow certain principles that betray their artificiality. He labels the first principle, according to which Herodotus invented his sources, “the principle of citing the obvious source.” For Fehling, this means that “Herodotus consistently cites as his sources those that are the most probable and natural ones if we assume that the events recounted are fact and the story is a genuine record of them.”

Often he “cites the inhabitants of the places in which the events occurred or from which individuals in them originated. . .” For example, when he relates a story about the Egyptians, he generally claims that the story derived from them as well. Fehling calls this a “national citation,” most instances of which, he argues, follow this “principle of citing the obvious source.”

It is hard to believe, claims Fehling, that Herodotus would have always stumbled on information from the “obvious source,” and this is what betrays the device as artificial. It also helps explain why his foreign informants tell stories that reflect Greek tradition.

According to Fehling, when Herodotus deems it inappropriate to ascribe material to the “obvious source,” he follows a set of additional principles to designate material to fictitious sources. These principles, claims Fehling, can also be demonstrated to follow a consistent pattern that betrays their artificial nature.

For example, Herodotus sometimes does not ascribe a story to the obvious source because he could not credibly have derived information from that source. Fehling calls this the “principle of regard for credibility.”

Other times, Herodotus does not ascribe a story to the obvious person or group because it would not have been in the interest of this party to tell such a story, perhaps because it was disadvantageous to do so. Fehling calls this the “principle of regard for party bias.”

Herodotus also often provides two or more variants of one story. In these instances one version either corroborates the other or corrects the other on a specific point. According to Fehling, it is hard to believe that stories that Herodotus often claims derive from widely distanced sources could so frequently and so neatly “dovetail” together. Suspicion of Herodotus in this regard has led Fehling to think that Herodotus often took a single story, broke it up into sections, and distributed it among several different fictitious sources according to the principles outlined above.

In Fehling’s opinion, “the purpose of this practice is quite clear. It produces a powerful illusion that a multiplicity of different and variously interrelated reports are being collected by the author’s tireless and wide-ranging investigations and piece together into a single narrative.” (pp. 20-21, my formatting)

That is all very theoretical so I will have to post some specific case-studies from Fehling’s book itself.

Hermeneutic of charity among non-biblical historians, too

Till then, I can’t bypass one footnote from Fehling’s book that is a sober reminder that not all historians are “good” historians. Too many are lazy and naive in both biblical and non-biblical historical studies. Apologists are not only found in theology departments:

Many scholars believe that every tradition has to be considered true until there is absolute proof to the contrary, as if there were some law of nature that prevents false traditions from arising wherever there is no means of checking. That is a principle that must inevitably lead to an over-credulous attitude in general and indeed to a degree of credulity in inverse proportion to the amount we know. It is a very partisan approach, since all undecided cases are counted in favour of one side, the apologists’, which thus extends to science the judicial rule of giving the accused the benefit of the doubt. In my own view the burden of proof passes to the apologists’ side once it has been established for a given category that (a) a sufficient number of cases are not authentic and (b) not a single case is demonstrably authentic. (p. 87)

So one can imagine that Fehling’s work, influential and enduring though it has been, has also been met with controversy. W. K. Pritchett, for example, charmingly designated Fehling and his followers “the liar school”. As one might expect, many attempts to counter Fehling’s arguments have fallen into the methodological trap of concentrating almost entirely upon those instances where Herodotus “could indeed be providing an eye-witness account.” (Stott, p. 22)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

what would be the difference all accounts being equal theoretically, in believing the geresene demoniac story as opposed to herodotus’s account of rats the size of city buses in india. herodotus may have been a bad historian, my goodness he’s pretty much inventing it as he goes along, but in my view he’s still the gold standard for that period at least. thucidides probably got more battles and politics correct.