Richard Carrier is interviewed by John Loftus on “Debunking Christianity”and the topic is mythicism and the place of Bayes’ Theorem. If mathematics helps clarify the thinking of many then it can only be a good thing. I personally have not seen that it is necessary, and that worthwhile thinkers routinely seek to identify and account for the assumptions, the details and identifying fallacies in their arguments. Good arguments do make explicit all the assumptions etc without the need for mathematics to draw them to our attention. That one is reading a story about an event and not directly accessing an event, the ability to examine the nature of the story itself, for example, or being able to justify clearly why an argument is “not persuasive or plausible” instead of just saying “that’s not plausible or that’s weak”, or why an event is more or less probable, and the careful weighing (with intellectual honesty) the alternative explanations, and that any chain of reasoning ultimately has to factor in its weakest link. . . .

The good and diligent historians do make these things explicit and clear. It is the muddle-headed ones, one might say, that don’t. If Bayes is going to help the latter then that’s not a bad thing. I really do think that much of the problem among theologians who identify themselves as historians have never really been “trained” in historical studies and have never been trained in logic or philosophy. Clear thinking skills — as evidenced by the regularity of circular arguments, special pleading, unexamined assumptions — seem minimal in all too many of their works that relate to “the historical Jesus”.

But as Richard implies, such clarity of thinking does not come to us naturally. It does take a lot of “training”. But I don’t agree that this sort of training need be the preserve of “experts”. Those with enough interest and effort can learn how to improve their ways of thinking and how they read works and formulate their own ideas. (And much of that training can come from wide reading of the very best in the field.)

Here are a few excerpts of the bits that particularly appealed to me:

Richard: As I go on to explain there, it really doesn’t matter to me, in the way it does to believers. I’m not invested in any theory proclaiming otherwise, and the historical Jesus, or perhaps I should say Jesuses (as there are several) proposed by mainstream scholars today pose no challenge to my worldview. If my method can be used to prove Jesus existed, I’d count that a win. Then we can finally move on to something else. I just don’t think that’s how it’s going to pan out in the end. But that’s calling the game too early. Let’s see what happens. . . .

. . .

Richard: Basically, every scholar who looks at the same evidence comes up with a completely different Jesus. As I show in the book, I’m not the only one noticing this. Many scholars in the field have been complaining about this for almost a decade now. If everyone applies the same method to the same facts and comes up with a completely different answer, there is clearly something fundamentally defective about that method. . . .

. . .

Richard: Quite simply, too many historians (and not just in Jesus studies; in every field) think they have made their case if they can come up with any plausible explanation. “Well, it could have been…” is assumed to be a sufficient rebuttal to anything. But that’s fallacious. . . .

The most obvious example of this mistake appears in fundamentalist “harmonizations” of Gospel contradictions: they think they have “rebutted” the conclusion that the Gospels are contradicting each other if they can think of “any” possible way to harmonize the accounts, developing a fanciful “just so” story that makes everything fit, by assuming a hundred things not in evidence. But that ignores the fact that that account is actually extremely improbable. That Matthew is deliberately contradicting Mark because he is arguing against Mark is vastly more probable than that Matthew and Mark are correctly describing exactly the same events. . . .

. . .

Richard: Not just sayings, by the way, but all facts, such as actions, events, and facts (like whether he was really ever a resident of Nazareth). I spent the most time on the argument from embarrassment because it is the most used, the most crucial for establishing historicity, and the most important for understanding why it is invalid. It then becomes an excellent model for seeing the deficiencies in all the other criteria, which are often much easier to see the faults of. The basic reason it doesn’t work is that it rests on assumptions that aren’t true most of the time, especially when applied to the documents we have for Jesus. . . .

When it comes to the crucifixion argument, the basic version you hear is that that was so embarrassing no Christian would claim it unless it were true. But this can be refuted with a single example: the castration of Attis was also embarrassing, yet no one would argue that therefore there must really have been an Attis who really did castrate himself. Arguably this was even more embarrassing than being crucified, as heroically suffering and dying for one’s beliefs was at least admirable on all the value systems then extant, whereas emasculating yourself was regarded as the most shameful of all fates for any man. Yet “no one would make that up” clearly isn’t a logically valid claim here. Attis did not exist, and a non-existent being can’t ever have castrated himself. So clearly someone did make that up. It’s being embarrassing did not deter them in the slightest. And in fact that is true throughout the history of religions: embarrassing myths were (and in all honesty, still are) the norm, not the exception. . . .

. . .

Richard: We do what honest historians have always done when this happens (and in my field, ancient history, it happens a lot): we conclude that we don’t know what happened. We might be able to say that some things are somewhat more likely than others, but that also several of those alternatives are not too improbable to rule out.

For example, did Alexander the Great ambush the Persians at Granicus, or charge pell-mell across the river and wage an amazing hand-to-hand melee with them in the water? The latter we have from an eyewitness. The former we have from a later informed expert. But the former is vastly more probable on prior evidence (of how battles and wars are typically waged, and how generals as successful as Alexander typically make engagement decisions, and what unit tactics we know Alexander relied on to defeat the Persian empire generally). So at best they seem equally balanced; and in fact, I am inclined to doubt the eyewitness. You could go either way. Certainly one of them is false. The evidence simply isn’t sufficient to know for sure. I think all honest historians who examined all the arguments pro and con would side against the eyewitness, but none of us would bet our lives on that conclusion. And so it goes. . . .

The full interview is here: http://debunkingchristianity.blogspot.com.au/2012/02/interview-with-richard-carrier-about.html

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

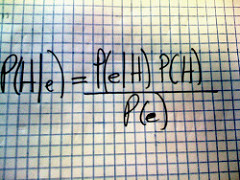

I’m afraid I’m inclined to disagree that the mathematics are not necessary, and that tightening up the reasoning can be done without it.

Many *accepted* forms of evidence are fundamentally flawed and yet are accepted by both lay and professional historians. Using Bayes’ Theorem as the backdrop for sound historical arguments is the equivalent of requiring biologists and psychologists to ground their work in sound statistical analyses. It’s tedious, but it is what keeps plausible sounding (but ultimately flawed) arguments from carrying the day. People are just naturally incompetent when it comes to assessing probabilities. I think the rigorous methodology of Bayesian analysis is required to settle what otherwise end up being conflicting, subjective probability assessments.

It does have the unfortunate consequence of making the endeavor more esoteric, but I expect that the analyses can be *expressed* and *explained* without the math–but only after they have been properly conducted according to correct Bayesian methodology.

If it’s any consolation I have in the past posted more detailed discussion about Bayes’ Theorem: Bayes’ Theorem Archive

I think the main problem I can see about the Bayes Theorem is that is sometimes difficult to quantify how much of a percentage point certain data should get. It seems that is subject to the opinion of the person inputting the data.

I am looking forward to Carrier’s book but I have seen a few implementations that he has done and I am unsure about the validity of the method for historical purposes.

The problem is not with some application of the Bayes Theorem, the fundamental paoblem is that it is applied to the writings of the NT which are in context written to image the mythical Christ of faith, not the man Jesus. The same must be said about mythicists in general, Carrier, et all.

An example that Carrier gave on one of his blog posts that convinced me that he’s on the right track went like this:

This would be a logical argument to use in history

P1: All major cities in antiquity had a public library

P2: Jerusalem was a major city in antiquity

C: Therefore, Jerusalem had a public library

This syllogism only works if we have 100 percent confidence in the major and minor premises. Even the slightest bit of doubt in either premise weakens the deductive strength of the conclusion. But usually historians might qualify their statements like so:

P1: All major cities in antiquity probably had a public library

P2: Jerusalem was probably a major city in antiquity

C: Therefore, Jerusalem probably had a public library

If we had actual numbers instead of the subjective “probably” statements, we could see how strong or weak our conclusion is. Bayes’ theorem would allow us a mathematically proven way of adding evidence (thus increasing the probability) to the major and minor premises to increase (or decrease) the strength of the conclusion or add other evidence to the conclusion.

Think of each premise as a coin flip. In order to find out the probability of flipping heads three times in a row, you have to multiply the probability of each coin flip since the next coin flip depends on the previous coin flip. The probability of flipping heads three times in a row is 50% * 50% * 50% = 12.5%. The same logic happens with the argument above. If 90% of all major cities in antiquity had public libraries, and we have 90% confidence that Jerusalem was a major city, this means there is an 81% probability that Jerusalem had a public library.

The same logic happens when using criteriology:

P1: The criterion of embarrassment says that people don’t invent things that are embarrassing

P2: The baptism of Jesus was embarrassing

C: Therefore, Jesus was baptized.

The conclusion is only as strong as the premises, yet the premises aren’t 100% certain. The only fact that we have here is that Mark wrote a story about Jesus being baptized. What is the probability that people in antiquity didn’t invent things that were embarrassing? What is the probability that the baptism of Jesus was embarrassing to Mark? If we have 75% confidence in both of those premises, this means that our conclusion is only 56% likely. Even though we have a reasonable amount of confidence in both premises, a conclusion that is only 56% likely isn’t that strong. Unfortunatley, NT historians have confused conclusions derived from criteriology with facts, when criteriology could only produce hard facts if they were 100% reliable.

Bayes’ theorem would be a way of adding to the probability strength of premises or conclusions, like finding a document in antiquity that attested to a public library being in Jerusalem. The document itself could be genuine or forged, so how much it increases or decreases the probability of Jerusalem having a library depends on the confidence we place on the document.

What Richard done has only achieved exactly what standard probabilistic analysis has done all along.

Its not as if one branch of stats and prob despises another..its just different ways..by probabilities or by experiment.

I would find it far more amusing that pieces of literature are analysed probabilistically (which would be a great outcome for Carrier and Ehrman) and extensively published as a adjunct to current dubious theological interpretations of “imported” sciences and pseudo sciences.

I am not at all sure that statements of the time are true or false and some subsequently propagated. It just they have that appearance.

In that may I add to our fellow J. Quinton, a probabilistic scenario of a genuine or forged document from a particular period BUT not before would be far easier to glean from statements around and following that period. This may be difficult to achieve, but its no where near as difficult to support as the assumptions we currently have

I’m not interested on how people interpret desires. Bayesian disproving the existence of a deity is about as relevant as evidential is no more and yet no less thorough than pointing out the ridiculous “disproving a negative” catch cry…

Normally all you can say to such catch cry is..”you have swapped your hypothesis”. All Bayesian probability says, geez, if you think this, you have badly weighted your conditional probabilities.

If anything, Carrier has been promoting what is as plain as the earth spinning in an easterly direction from where you stand from conservatism’s position of, the sun rises every day..

Its a sad reflection in this modern scientific world that Richard has to point these things out.