Joel Watts, now a master of theological studies, has posted The Schizophrenia of Jesus Mythicists. Since I am always on the lookout for serious arguments addressing the Christ myth argument I had hoped that, despite a title imputing mental illness to those who argue Jesus was a myth, I would find engagement with a mythicist argument. But, sadly, no.

Joel Watts, now a master of theological studies, has posted The Schizophrenia of Jesus Mythicists. Since I am always on the lookout for serious arguments addressing the Christ myth argument I had hoped that, despite a title imputing mental illness to those who argue Jesus was a myth, I would find engagement with a mythicist argument. But, sadly, no.

Watts does not want anyone to think he is merely defending a faith-position. He explains that his post is about “verifiable proof” and is not a “matter of faith”.

I can accept that approach. Faith is about things we cannot prove or see. Verifiable proofs would undermine faith. One can only believe Jesus was resurrected and is God etc. by faith. (Does not N.T. Wright undermine faith in the resurrection of Jesus when he claims to have historical proof of the resurrection?)

But here Watts is talking about the historical man, Jesus. His faith presumably would be harder to sustain if there were no generally recognized human of history at the start of it all. So, like Marxists, he must first believe in history.

Here is his argument against mythicists and for “verifiable proofs”:

Remember, the birth narratives aren’t in Mark, but were added by both Matthew and Luke. I would say it was added by Matthew and expanded by Luke. Notice Matthew’s pattern of the validation of Jesus by the Old Testament. This is where the idea of prophecy must be understand (sic) as employed by Matthew. It wasn’t about making predictions and fulfilling them years, decades or centuries later, but for Matthew, it was validation of the mission of man of Jesus. For instance, the arrival from Egypt is put next to Hosea as a way of validating Jesus as the incarnation of Israel. So then, literally speaking, the naming of Jesus to mimic Joshua could have been ‘invented’ by Matthew as a further validation of Jesus and his mission. This doesn’t take away from the reality of Jesus as a historical person (or even the idea held by Jesus and his disciples that he was to be the second Joshua), but follows Matthew’s actions of validating Jesus through the Hebrew Scriptures. Names signify missions and were a special dispensation of God.

I can fully agree with nearly everything Joel Watts has written here. No argument. Early Christians used the Jewish scriptures to “validate” Jesus and even their own place in history as evangelists for this Jesus. The only quibble I have is the implication in his last sentence that God gave Jesus his name. If we are talking about verifiable proofs and not matters of faith I would suggest it is more reasonable to think that Jesus acquired his name in a manner consistent with how anyone acquires their public name.

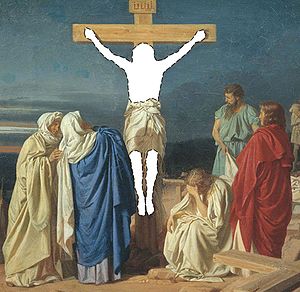

One more thought (put into my head by Tim, so blame him for this). It is easy to structure an argument around the clearly mythical nature of the birth narratives. But mythicists that I have read don’t use those to clinch a case that Jesus was mythical any more than historicists use them to argue Jesus was historical. But the Passion Narratives are surely just as mythical, filled with as much supernatural happenings and validated just as thickly from OT scriptures as the birth narratives. Angels appearing in Gethsemane, disciples fleeing according to the prophecies, Jesus silent before his accusers according to the prophecies, miraculous darkness at noonday, Jesus’ clothes parted according to the prophecies, Jesus’ last words according to the prophecies, Jesus miraculously resurrected from the dead. Why do historians generally dismiss the birth narratives as having no historical basis while at the same time generally accepting the Passion narrative as historical?

Anyway, Watts continues:

The problem with mythicists, and there are many, boils down to the simple fact that they still take Scripture as if it was written with the same standard of fact which Westerners have and they miss the subtle things which are extremely important in decision making. Simply because Matthew validated Jesus’s mission by various Old Testament passages, this does not take away from the reality of Jesus’ existence. I mean, Vespasian’s reign, and in some ways, his existence, was validated by the Jewish Scriptures as well, and yet, no one doubts that he was actually Caesar. An excellent book on evidence of Jesus outside the New Testament can be found here. I doubt that I’ll get to blog through it anytime soon, but hopefully.

I don’t follow the first sentence here. By using the word “Scripture”, whether applied to the OT or NT, it seems to me that Watts is viewing the writings of the Jews and Christians as faith documents. But even if not, I don’t know anyone (apart from fundamentalists or conservatives) who consider them as genuinely factual narratives.

I do, however, follow and agree with the next sentence: “Simply because Matthew validated Jesus’s mission by various Old Testament passages, this does not take away from the reality of Jesus’ existence.”

True. Agreed. But only if we have established the reality of Jesus’ existence to begin with. One might just as plausibly express the same idea as: “Simply because Matthew validated Jesus’ mission by various OT passages, this does not mean Jesus was himself a myth”.

That is 100% true. No argument.

I have said many times — it is a simple truism — the fact that Egyptian, Greek and Roman kings and emperors identified themselves with various gods or semi-divine heroes does not mean that these figures did not exist in real life. It is silly to suggest otherwise. So what makes it different with Jesus? What makes it different is that when you remove all the mythological claims that were attached to a clearly historical figure we are left with lots of the historical figure left over that is not mythical. We are left with many other accounts independently testifying to the historicity of these figures. With Jesus, however, remove the mythical — that is, remove the “Christ of faith” from the gospels — and you are left with empty pages. Nothing is left remaining.

This is why historical Jesus scholars say they cannot rely on the Gospels as historical documents and why they must, as they say, “dig beneath” the words of the Gospels. They speak of “getting behind” the narrative about Jesus.

The question then should be: how will one know what it is that one finds “behind the text”? How will one know whether what one imagines to be there is anything other than an imaginary figure? Is not such a figure going to be yet another Jesus of faith? The doppelganger of one’s Christ of faith?

I happen to think there are valid ways to reach a valid conclusion.

If one finds that a narrative is made up of phrases and ideas from other literature, and there is nothing to the narrative of Jesus that cannot be identified as a borrowing from other literature, then is it not a valid conclusion that Jesus was a literary creation?

.

Watts links to a book by Van Voorst as if that volume supplies all the evidence for historicity that one might need. I found Voorst’s book so redundant and elementary I have not bothered to write about it much. Only passing references here and here. But Earl Doherty has done a fuller treatment of it here. Now what I’d like to see is a scholar seriously engage with that critique, but I will not be holding my breath.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“The problem with mythicists, and there are many, boils down to the simple fact that they still take Scripture as if it was written with the same standard of fact which Westerners have…”

Perhaps because its peddled that way in the churches. When you say to a Westerner, or rather make him quote from a creed saying “I affirm that the Bible is the inspired, inerrant, and infallible word of God, and that all of it is true” then you are tricking him into thinking you mean it is true in a rational Western sense. If he knew you meant that its true the way any old Eastern fairy-tale is “true” then he would stop attending church and paying you the tithe! So, the “schitzophrenic” who is trying to have it both ways is the Christian pastor, not the mythicist.

Speaking of schizo…

…phrenia…

What, no gay Jesus? When in Singapore I saw pictures of a Hindu Jesus, too.

If one finds that a narrative is made up of phrases and ideas from other literature, and there is nothing to the narrative of Jesus that cannot be identified as a borrowing from other literature, then is it not a valid conclusion that Jesus was a literary creation?

I’m not sure. The fact that nothing but the literary Jesus remains wouldn’t seem to be quite enough to establish that the literary Jesus is all there ever was. I

It is not a dogmatic conclusion. But it is valid one. There are additional arguments that strengthen the case for a more certain mythicism. But the validity of the entirely literary Jesus lies in the fact that the literary IS an explanation in the absence of other evidence (of the sort usually undergirding historical persons) that such a Jesus exists.

I think we have enough examples of historical people becoming heavily mythologized that it is reasonable to believe that a real person could become so heavily mythologized that nothing historical could be recovered. I think we have few examples where we can verify that an entirely mythological or literary creation came to be accepted as a historical person in the way that mythicism proposes. That does not make mythicism impossible or implausible, but I do think it makes it hard to assess it as most likely.

Most human beings who lived in first century Palestine left no mark in the historical record whatsoever so I’m not sure how the absence of evidence of the sort usually undergirding historical persons would warrant anything other than agnosticism.

‘I think we have few examples where we can verify that an entirely mythological or literary creation came to be accepted as a historical person in the way that mythicism proposes. ‘

Apart from the Magi, Adam, Eve, Cain, Abel, Moses, Noah, Jannes and Jambres, Melchizedek, Abraham, Elijah, Baal, etc, etc, we have very few examples.

I wonder if there are any Enoch-agnostics out there? (asked the Jesus agnostic)

I don’t think the mechanism by which those characters came to be thought of as historical is quite the same as what mythicists think happened with Jesus.

Would you agree that a good number of HJ scholars view Judas Iscariot as a mythical figure? By what process do you think such a character became historicized?

Judas seems to be playing a role in a literary creation. Beyond that he is Judea personified, betraying the Messiah, and becoming responsible for his death. I think the fact that scholars can imagine a process by which Judas went from fictional scapegoat to “real, live, historical guy” means that we do have at least one example “where we can verify that an entirely mythological or literary creation came to be accepted as a historical person in the way that mythicism proposes.”

Tim,

I don’t think that imagining is verifying. I think the nature of our sources for Jesus are so problematic that the best a historian can do is to lay out some possibilities and I think that mythicism is one that belongs in the mix. However, to say that mythicism is the most likely explanation of Christian origins would seem to me to require something more than that.

Also, it seems to me that using a character within the New Testament tradition to draw conclusions about other characters within the same tradition is not as compelling as finding examples from outside the tradition.

Would a character from the apocrypha be compelling, or do we need something further afield?

Ned Ludd is frequently offered up as an example, but I’m told his case isn’t compelling either. I’m not sure why that is. Perhaps he’s too modern to be a compelling example.

Are we looking for an example from ancient history? To help us with our aim, where are the goalposts?

I think that Ned Ludd is a good example that this kind of thing can happen, but I don’t know it mandates the conclusion that it did happen in the case of Jesus.

Obviously the more examples we have from more diverse times and cultures, the better chance we would have of generalizing the factors that distinguish a purely literary creation from a heavily mythologized historical person. I’m not sure how much it would take though.

I think Juan Diego is a great example, but I guess I’m one of the few.

Fascinating the way that the linked Doherty article he refers to “Price” (who I assume to be Robert M. Price) and attempts at refuting mythicism. Dr. Price is himself now a mythicist. If I recall correctly, he was convinced by the arguments of Doherty and Wells.

I find your comment interesting, because of a confusion I had anticipated.

That is exactly the mix-up that I feared could happen when I was reading the “Alleged Scholarly Refutations of Jesus Mythicism (with comments on “A History of Scholarly Refutations of the Jesus Myth” by Christopher Price)”.

I was struck by the repeated mention of the bare name of “Mr. Price” or “Price” in the text, pages and pages away from the title, whereby I had to stop and wonder whether Earl Doherty meant “our” Price, that is Robert M. Price. I had to conclude it couldn’t be, given the whole context of the critique.

But I immediately feared that many readers might think that the mention was of Robert M. Price, a name that anybody interested in Jesus mythicism is familiar with, while few people are aware of this “Christopher Price”. Even though he is well presented in the introduction to the articles, but soon forgotten as one plunges into the ocean of text.

I alerted Earl Doherty by email that it was a mistake not to spell out the full name of “Christopher Price” to prevent the spontaneous confusion with Robert M. Price.

I didn’t hear from him on this subject, and I have not checked out since if he has made the correction in his original text.

Indeed. I was actually telling Dr. Price about it and ge was shocked because he didnt think he had ever said those things. As I was sending him the URL I noticed that it was Christopher Price. Doh!

JOEL

Names signify missions and were a special dispensation of God.

CARR

Joel hits the nail fairly on the head with his insights.

Philiippians 2

And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death– even death on a cross! 9 Therefore God exalted him to the highest place and gave him the name that is above every name, 10 that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, 11 and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

It should be pointed out that mainstream scholarship is unanimous in claiming that when Paul says that every tongue will confess that ‘Jesus Christ is Lord’ they will be using ‘Lord’ as a name. You might think ‘Lord’ is a title, but it is not. It is a name.

Or alternatively that when Paul stresses that it is the name of Jesus that bows every knee, he does not mean the name ‘Jesus’. He means some other name which is not mentioned by him or any other Christian anywhere.

In fact, any explanation will do which removes any suggestion that when Paul stresses how the name of Jesus bows every knee and that everybody confesses that ‘Jesus Christ’ is Lord, he is talking about the name ‘Jesus’ as being an important name,

Sorry, Josh. “Price” throughout my ‘Refutations’ article refers to Christopher Price, a fairly well-known (or at least he used to be) apologist on the Internet. I made this clear at the beginning of the three-part article, but I should have ‘reminded’ the reader regularly throughout.

My apologies, too, to Robert Price.

I might add the comment that my “Alleged Refutations of Jesus Mythicism” article (my thanks to Neil for linking to it) stands up very well after some six years, although many discussions in them were much expanded in Jesus: Neither God Nor Man. The only exception is my tentative “agreement” with the view that the reference to Christ and Christians in Tacitus is probably genuine. I now regard it as almost certainly an interpolation, considering that no Christian commentator before around 500 CE indicates any knowledge, not simply of the Tacitus reference, but of any persecution and martyrdom of Christians by Nero as perpetrators of the Great Fire. (One of these days I’ll get around to going through my website articles and bringing points like that up to date!)

I’m curious. Can anyone offer a “so heavily mythologized” figure in world history that nothing of an identifiable historical nature is recoverable about him/her, yet we can ‘know’ that he or she was indeed historical, and on what basis? Does Watts?

Earl: “. . . and on what basis? Does Watts?”

I think you need to hear voices in your head to know the answer to that question. So I guess that means you’re a schizophrenic, because you can’t hear those voices.

It’s an odd sort of mental disease you have there — you don’t have imaginary friends, you don’t see things that aren’t there, and you don’t believe in things you can’t prove. How long have you had this illness?

Totally coincidence, but while Neil and I were talking about the ahistoricity of the Passion narrative, Mark Goodacre was cooking up a post that features this old clip of John Dominic Crossan introducing his theory of “Prophecy Historicized”:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=EUxTVGiHLco

What Crossan is describing here is exactly the model advanced by the argument that Jesus was a mythical/theological/literary creation. The only difference is that Crossan says it was made up by people who knew nothing about the death of Jesus but who had had contact with Jesus before his death, while mythicists say it was made up by people who nothing about a historical death, period.

In other words, the only difference is accounting for the background to the (unknown) authors of the story.

Judas? “Made up.”

Centurions at the cross? “Made up.”

Jairus? “Made up.”

Bethlehem birth stories? “Made up.”

Passion narrative? “Made up.”

Jesus? “Made . . . oops. I mean, why would anybody make it up?”

Joel Watts, having the entire resources of Biblical scholarship on his side , is reduced to defending his position in his article by calling people ‘insane’.

They said Jesus was insane, too. . . . So we are in good company, yes????

“I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Him: I’m ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don’t accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

How ironic that you would post pseudoepigrapha (not merely quoting C.S. Lewis, but posting under his name as if you were Lewis himself), but do so while completely missing the point of the topic of this and many other posts on this blog. The Lewis Trilemma (“Lunatic, Liar, or Lord”) fails to account for both of the positions being discussed here: Legend (that is, a fairly ordinary historical man around whom a body of embellished tales arose) and Lore, a.k.a. “mythicism,” the theory that Jesus was originally revered as something akin to a “channeled entity” like Ramtha or Seth in the modern New Age movement, his existence, nature, and deeds being “discovered” via a mystical reading of the Hebrew Scriptures as a “Bible Code” along with various mystic visions and experiences. Or in other words, Jesus was a mythic deity comparable to Osiris or Hercules and never had any historical existence as a man on Earth. So now we have five options (Liar, Lunatic, Lord, Legend, Lore) instead of the three Lewis would have wanted us to choose from. The existence of Legend and Lore as options (something that simply cannot be missed if you read any post on this blog, including the one to which you replied) completely de-fangs Lewis’ gambit.

You are, of course, not the first Christian to engage in the practice of pseudoepigrapha, writing under the name of a renowned figure of the past. That’s how the “pastoral” epistles (supposedly by Paul), the epistles of Peter, and much other Christian and Jewish literature (e.g. the Book of Enoch) was produced.

So, we have a perfect trifecta: pious fraud, willful ignorance, and the use of arguments that completely fail to engage the positions you’re arguing against.