Continuing my little series of posts reading the Bible in the context of popular ancient fiction, specifically with the Argonautica.

Continuing my little series of posts reading the Bible in the context of popular ancient fiction, specifically with the Argonautica.

Book 4 — Seaton’s translation of the fourth and final book of the Argonautica. (Ignore the chapter numbering in the title.) This post covers only the early portions of this book.

Escape adventure and happily disbelieving reunion

Having thrown her lot in with Jason Medea flees her father’s palace under cover of darkness fearing his wrath. As she rushed forth from her home,

the bolts of the doors gave way self-moved, leaping backwards at the swift strains of her magic song. . . . Quickly along the dark track, outside the towers of the spacious city, did she come in fear; nor did any of the warders not her, but she sped on unseen by them.

Peter is not a semi-divine being as Medea is (she is a granddaughter of the sun god Helios and has magic powers) so he needs an angel to help him out when it is his cue to enter this Hellenestic adventure motif of fleeing for his life, past guards unseen, with doors opening of their own accord:

And he went out, and followed him; and wist not that it was true which was done by the angel; but thought he saw a vision. When they were past the first and the second ward, they came unto the iron gate that leadeth unto the city; which opened to them of his own accord: and they went out, and passed on through one street; and forthwith the angel departed from him. (Acts 12:9-10)

When Medea comes near to Jason’s camp she calls out to her nephew Phrontis who had earlier joined him and the Argonauts. They were by no means expecting Medea to turn up like this, and in their surprise, both knew and did not know her voice:

Then through the gloom, with clear-pealing voice from across the stream, she called on Phrontis . . . and he with his brothers and [Jason] recognizes the maiden’s voice, and in silence his comrades wondered when they knew that it was so in truth. Thrice she called, and thrice at the bidding of the company Phrontis called out in reply . . .

The crew led by Jason then went out to fetch her and bring her into their company.

Peter is also recognized by his voice when he comes to the assembly of the brethren. Yet for joy they think it must be the voice of his angel, and not really of Peter. He must stand there a while longer until he is allowed to join them. It’s a wonderfully entertaining and moving scene worth repeating in any adventure tale.

And when he had considered the thing, he came to the house of Mary the mother of John, whose surname was Mark; where many were gathered together praying. And as Peter knocked at the door of the gate, a damsel came to hearken, named Rhoda. And when she knew Peter’s voice, she opened not the gate for gladness, but ran in, and told how Peter stood before the gate. And they said unto her, Thou art mad. But she constantly affirmed that it was even so. Then said they, It is his angel. But Peter continued knocking: and when they had opened the door, and saw him, they were astonished. (Acts 12:12-16)

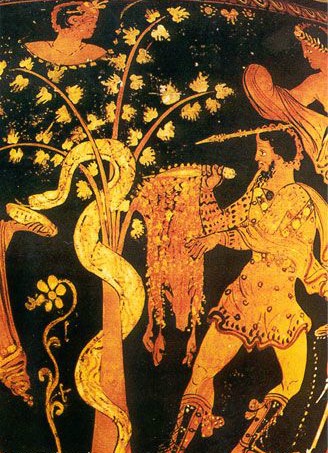

The serpent and the fruitful tree

Medea offers to use her powers of sorcery to enable Jason to now take the golden fleece from the sacred oak tree guarded by the serpent. (This is now Jason’s right by virtue of his having passed the contest set by King Aeetes.) When she charms the serpent to sleep Jason takes his prize.

Medea is then hailed as “the glorious saviour of all Achaea” and the reputation of all Greece is bound up in the success of Jason and the Argonauts:

And now in our hands we hold the fate of our children and dear country and of our aged parents; and on our venture all Hellas depends, to reap either shame or failure or great renown.

The Bible’s first adventure story is about a famous tree and snake and divine sanctions and needs no elaboration. What is interesting is the recurrent theme that such adventures worth the telling are important enough to have implications for a far larger stage than the immediate setting. Similar critical moments in the Bible involving individual acts of courage or folly affect the whole of a nation, or tribe or city or the entire human race.

Medea enables Jason to take the fleece by inducing the serpent to sleep. It may sound banal to draw attention to sleep as a motif, but I do find it intriguing the way sleep is used at critical junctures in both popular secular literature and critical moments in certain Bible stories. In Homer’s Odyssey, the hero Odysseus goes off alone to pray when he knows his followers are facing a supreme temptation that could lead their deaths, and it is while he falls asleep in prayer that his followers fall into that very sin against Apollo by sacrificing his sacred cattle. It was while Samson slept that he lost his strength. And of course we have the sleeping disciples of Jesus in Gethsemane. In this moment in the Argonautica, it is the evil power that is put to sleep, not the righteous one. (Sleep is also the time when God/the gods send dreams and messages and lives change direction. Sleep is also a universal metaphor for death.)

Opposition and crisis

Once Medea’s acts on behalf of Jason, and her fleeing from her family, were known to her father, the king Aeetes, he assembled all his army and threatened their own lives if they failed to recover his daughter. Aeetes placed Medea’s brother, Apsyrtus, at their head. Thus was launched a massive army in “so mighty a host” of a “fleet of ships” that it resembled “a countless flight of birds, swarm upon swarm . . . clamouring over the sea” in pursuit of the single ship, Argo, fleeing with Jason, his crew and Medea.

The Bible loves this trope, too. The moment the Israelites flee from Egypt, Pharaoh feels he has been tricked and leads his entire army out in pursuit of them. So the suspense is maintained. The reader knows how small or comparatively helpless the heroic ones in flight are against the might of the pursuing army.

King Saul, like Aeetes, in his haughtiness issues a vain threat against his own army (and son) when in pursuit of his enemies (1 Samuel 14). Wicked kings traditionally took extreme measures to kill off those who had crossed them or were deemed a potential threat. Herod is another.

Medea’s flight from her homeland was accompanied by a sacred rite too holy for the author to describe.

Now all that the maiden prepared for offering the sacrifice may no man know, and may my soul not urge me to sing thereof. Awe restrains my lips, yet from that time the altar which the heroes raised on the beach to the goddess remains till now, a sight to men of a later day.

Israel’s momentous escape was also associated with the sacred rite of the Passover, and that story is told as a memorial of that escape, just as Medea’s escape is told as the reason for a sacred altar of a later generation.

Change of course, guiding heavenly fire — and a new series of adventures

Jason had been earlier warned by the prophet Phineus to return by a different route from which they came to the golden fleece, and was at this critical time reminded of that warning. But by taking this new route they will find themselves facing a new set of adventures before they return to their homeland.

The new way for them to travel was revealed to them by “a trail of heavenly light”

and the gleam of the heavenly fire stayed with them till they reached Ister’s mighty stream.

But their pursuing foe knew a short cut and cut them off at the pass:

then indeed the Colchians [King Aeetes’ army led by Medea’s brother, Apsyrtus] went forth into the Cronian sea and cut off all the ways, to prevent their foes’ escape.

The same dramas resonate in the Bible, especially with the Exodus story. The Israelites had planned to return to Canaan by the same route that their fathers had entered Egypt, but were warned by God to take a different route, one that would involve them in many hard trials for 40 years.

Similarly, when Jesus’ family were returning to their home they were warned by an angel to take a different route and avoid the areas where potential enemies still lurked.

The pillar of fire that showed the Israelites their way needs no further mention. In Acts, the fire falls in tongues upon the apostles, showing all witnesses that “the way” was now with them.

And the Egyptians trapped the fleeing Israelites against the Red Sea as surely as Aeetes’ army trapped the fleeing Argonauts.

Escape, sin and the reproach on womankind

Jason acknowledges his plight and sensibly makes a gentleman’s agreement with the commander of the enemy forces, Apsyrtus, who is also Medea’s nephew. King Aeetes only wants his daughter, Medea, returned. He acknowledges he lost the golden fleece in a “fair contest”. Jason and Apsyrtus agree to place Medea in a holy temple of Artemis (a neutral space) until a neutral king should decide her fate, whether she should return to her father or go with Jason.

This is when Jason learns it is never a good idea to elope with a woman who can weave magical spells (i.e. a witch). Medea, “seething with fierce wrath“, cowers Jason as she reminds him of his oath to rescue her from her father in return for enabling him to win the golden fleece, and that as a result of her betrayal of her father she has “poured on womankind” “a foul reproach!” Jason tried to get her to see reason: that if the “monster-teaming” army of Apsyrtus slaughtered them all they would force her back to her father anyway with even greater indignity as a captured maid. But it was a male-female thing so he had no chance of winning the argument.

Medea tells him how to keep his promise. She will trick her nephew, the army’s commander, into falling into an ambush to be set by Jason. Jason would murder him, hide his body, then escape with her and his crew. Once the enemy forces discovered their leaders’ death they would disperse and leave them alone. Such is the evil wrought by the god of Love.

Ruthless Love, great bane, great curse to mankind, from thee come deadly strifes and lamentations and groans, and countless pains as well have their stormy birth from thee. Arise, thou god . . . as when thou didst fill Medea’s heart with accused madness.

So Jason treacherously murdered Apsyrtus. As part of the rite to atone for such a duplicitous murder he licked up his blood and spat it out again three times, but this did not remove the necessity to hide the victim’s body. The treachery would also lead them into a renewed set of trials before their final homecoming could be permitted.

And of course it is also the woman’s fault that man sins in the Bible, too. There it is Eve who became “a foul reproach poured on womankind.” Paul’s and the Pastoral epistles reinforce this message.

Likewise, when Israel escaped from Egypt they immediately fell into the sin of faithlessness, and were also doomed to change course and wander through many more trials for 40 years before reaching their new homeland.

The same theme is “disembodied” or “spiritualized” in Christian literature, where it is “Christ who is made sin” that brings about the hardships of persecutions and heroic endurances and overcomings upon all those who follow Him.

Next: “chapter 6” continuing this fourth book of the Argonautica

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!