Continuing the story in Book 1 (links to Seaton’s translation) of the Argonautica. It is one of many ancient works of literature that deserve to be read alongside the Bible to keep everything in perspective. [This is the second part of my little series of posts reading the Bible in the context of popular ancient fiction, specifically with the Argonautica.]

Prayer, promise, loss and suffering

Before embarking on their quest for the golden fleece, the leader of the expedition, Jason, utters a lengthy prayer to Apollo, the god of his fathers. His prayer reminds Apollo of promises the god made to him in the past, seeks protection, offers devotion, and announces that all will be done for the god’s glory. Following the prayer a number of sacrifices are offered. In their wake, one of the crew, Idmon, pronounced a prophecy declaring final success for the mission, but only through many trials and tribulations, including death for himself. The crew listened with mixed feelings, rejoicing in the promise of eventual success, but mournful at the fate of Idmon.

Jason’s prayer is matched by Solomon’s prayer at the inauguration of the Temple and the beginning of the new era for Israel under God. God is reminded of his promises, protection is sought, and God’s name is to be glorified. At the Amen, the sacrifices begin. But with the prayer are hints that not all will be well. Readers are reminded of the history of failure of Israel. There are many such prayers throughout the Bible. Jesus prays for the safety of his followers, conceding that one must be lost according to the divine pre-ordained will. All prayers acknowledge the necessity that the godly must suffer severe trials before they reach their final reward.

The leader sets himself apart, and is challenged, but music restores the calm

The crew, the argonauts, quickly forget the sober moment when evening falls and it is time to rest, tell stories and feast with wine. Their leader Jason, however, cannot share with them their carefree spirits. He is too burdened with the full awareness of the dangers ahead, and his responsibility of leading them all safely. Like Homer’s Odysseus before him when he knew too well the dangers that faced his crew, and who likewise left them in their carefree state of mind to go off alone to pray, Jason withdrew himself.

But one of Jason’s followers notices his master’s withdrawal and heavy looks, and rebukes him:

And Idas noted him and assailed him with loud voice:

“Son of Aeson [i.e. Jason], what is this plan thou art turning over in mind. Speak out thy thought in the midst. Does fear come on and master thee, fear, that confounds cowards? Be witness now my impetuous spear, wherewith in wars I win renown beyond all others (nor does Zeus aid me so much as my own spear), that no woe will be fatal, no venture will be unachieved, while Idas follows, even though a god should oppose thee. Such a helpmeet am I that thou bringest from Arene.”

Idas rebukes his leader for fearing the worst. Idas reminds Jason that he will never desert him, but protect him in any circumstance. No harm can come to him with Idas by his side. But Idas is proud, and trusts his own will and strength more than the grace of Zeus.

Idmon, the one whom prophecy had foretold would die, turned on Idas to rebuke him for his proud arrogance, warning him that such a boastful speech and rebuke against Jason was sure to bring down divine punishment upon him. Proud Idas in turn reviled him with heated scorn.

Only the intervention of Jason himself and his comrades prevented the quarrel breaking out into violence. Calm was restored, the evil passions banished, when Orpheus then took up his lyre and began to sing.

Jesus also was too conscious of the fate that lay ahead for him and his disciples to share their petty chatter and worldly concerns. He also left them to go off alone to pray for strength to face the coming trials. His comrades were too unaware of the dangers they faced to appreciate his troubled soul or stay awake with him.

His disciples could only think of how much the ointment used on him cost. They were indignant, one of them so much so that he went off to betray him. (Why is it that Idas looks like it should sound somewhat like Judas?)

Another disciple, Peter, had twice admonished Jesus, like Idas, that no harm need come to him while he stood beside him, and that he, Peter, would never desert him or let him down. Jesus had to rebuke him that he was mindful of proud human ways, and not the ways of God. Even at the last supper the disciples quarreled about who should be greatest in the kingdom, and Jesus had to rebuke them to restore peace and right thinking.

Absalom also criticized the ways of his father David.

The prophet Elisha also had to call for a musician to help restore calm and peace of mind (1 Kings 3:14-15); David found himself required to play music and sing several times to appease the evil spirit in Saul; and even the disciples with Jesus sang a hymn between the tense moment of the last supper and going out to Gethsemane.

Sacred vessels, lots and etiologies

The Argo itself contained a timber beam from an oak that had been sacred to a shrine to the Mother Goddess Dione (Dodona) and accordingly had the gift of prophecy. A strange sound from the harbour itself joined the Argo in urging the Argonauts on to their mission. Then, lots having been cast to assign where each hero was to sit in the Argo, the voyage began.

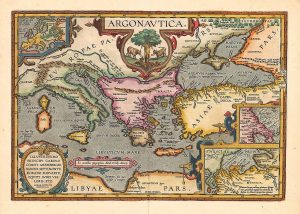

The details of the journey are listed, the places they pass, the descriptions of them receding out of site as new places up ahead come into view, whether the places are covered in mist, where the shore is calm, where they see cornfields or tombs, when they face difficult headwinds — the reader is immersed in the “eyewitness realism” of the richness of the author’s imagery. Some places where the Argo berthed to pause for fairer weather or to allow the crew to offer sacrifices were subsequently named after the Argo, such as the beach known as Aphetae [=Starting] of Argo.

Another sacred vessel, the ark of the covenant, would cause statues to fall down before it (1 Samuel 5), and rivers to part (Joshua 3). In the stories of Jesus voices were heard speaking from heaven (Mark 1:11; John 12:28-29). At the beginning of the church’s launch, a great sound of a wind came from heaven (Acts 2:2) around those chosen to lead its mission.

Lots were cast to see who should share in that mission, just as lots were cast to learn the will of God in the days of the ark of the covenant.

The journeys of the Patriarchs, and then of the Israelites under Moses as they wandered through the Sinai, and even the travels of the apostles in the New Testament, are all dotted with place names and accounts of special happenings at many of them. Anyone with passing acquaintance with ancient tales like the Argonautica must surely question biblical authors who insist such details betray the historicity of the account.

Many of the travel tales are etiologies. Names are assigned to places where something memorable was experienced, such as the naming of Bethel (House of God) where Jacob had a dream that he was at the entrance of God’s house.

Women!

On the island of Lemnos lived women who had all united in murdering their husbands, their female slaves and all their sons who might otherwise have avenged them. They were led by Hypsipyle who had secretly spared her own father by hiding him in a chest and floating him out to sea. He was eventually rescued by fishermen. The women of Lemnos were thus left to tend the work of the fields that the men had once done (which was “easier than the works of Athena” that had once preoccupied them), yet they lived in constant fear of their crime being discovered. So when they saw the Argo approaching their queen, Hypsipyle, called and assembly to discuss plans of action.

After hearing one option advanced by Queen Hypsipyle — to keep the sailors out of their city, give them what they needed, and send them quickly on their way — Hypsipyle’s aged nurse, Polyxo, staggered on her withered feet and bending over her staff proposed an alternate, and wiser, plan. Her presence is adorned by the mention of four virgins seated beside her. She advised the assembly to think of their future, how they would all one day age as she, and would need younger ones to do the work to supply their needs. Invite the men in. Let them become protectors of them against their fears of vengeance, and father children to take care of them in their old age. Her counsel proved the most persuasive and the assembly agreed to her plan.

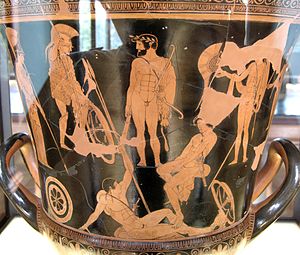

Messengers were sent and Jason and he prepared to meet the queen by dressing in his most glorious robes prepared for him by the goddess Athena. Readers are invited to see every detail of this “purple mantle of double fold”, with its woven multi-coloured scenes of Olympian gods, pastoral settings, chariot races, and more.

Dressed in divinely woven garments Jason awed the onlookers as he made his way to Hypsipyle. The queen invited Jason and his men to stay with them and make Lemnos theirs, explaining to him that their menfolk had betrayed them for other women they had captured in raids, and left them to fend for themselves.

Jason replied that he could not stay, but he did stay longer than Heracles liked. Heracles, with a few chosen comrades, kept himself back from the temptations of the women and refused to enter their city. In irony he complained that his men were not delaying because of “murder of their kindred” but for the preferring to marry strangers rather than women from their own countries.

Heracles rebuked them all with these accusations, and like shamed children they lowered their eyes and silently returned to the Argo and their rightful calling.

This trope is found over and over. In the Odyssey, in the Aeneid, the heroes and their followers are for varying periods of time led astray by women whether sorceresses or human. Often a god has to intervene to remind them to get up, leave, and get on with their journey.

The partings from such unions are often narrated with compassion. Though Jason has been foolish in delaying with Hypsipyle they part with Jason leaving instructions for the future of their son expected from their time together.

The saving of one person in a casket floated out to see reminds us of the Moses story, of course. There are many parallels in the literature.

The calling of the assembly and the ensuing speeches are favourite scenarios in epic and popular literature of Hellenistic times. Kings and lords would gather and poets delighted to deliver rival speeches through each of them and invite the hearers to witness the impact each had on their assemblies. We find this at the centre of the Acts romance, with the Jerusalem conference called for church leaders to debate the issue of gentile converts. First one gets up and speaks, then another rises to give an alternative view point. The matter is finally settled when one venerable wise one delivers a word all agree is the most inspired. In the Old Testament it is a wise woman who saves a city from doom with her words, too (2 Samuel 20). Paul’s stay with Philip, an inspired evangelist, is made more notable by the mention of his four virgin prophetess daughters.

Modern readers quickly tire of all the minute detail of the descriptions of the curtains of the tabernacle, the priestly garments, and measurements of the buildings. But these details were in demand by ancient readers, as we can learn from the regularity with which similar minutiae of the artistic work that has gone into battle shields, cloaks of royalty, and temple measurements.

The Bible, of course, has the same topoi of the women who tempt men to divert them from their calling. Eve was only the first. The Moabite women lead all the Israelite men astray, though the Bible modestly stresses their sin as worshiping their pagan gods. Such a high minded devotional lot they all were, even under the sway of feminine temptations. (Numbers 25). Only Phinehas and a few chosen (such as Moses himself) kept themselves from temptation. Phinehas did better than Heracles, however. Rather than waste time with words he put a stop to the shenanigans by thrusting his spear through a couple of bodies in one blow. But there was an earlier moment when words were enough, well almost, when Moses shamed them all for having “made merry” around the golden calf while he had been spending his time collecting commandments from God on the mountain.

Though David committed adultery with Bathsheba he was still permitted to have a son with her to be his heir. Solomon was also led astray, and he, too, was rebuked, but without effect. By the time of the New Testament, sex sins have become a metaphor for idolatry or apostasy.

War and peace

The Argonauts are attacked by Earthborn monsters hurling huge ragged rocks, but Heracles and others defeat them with their arrows and spears. In the evening the crew return unknowingly to a place they had earlier been during the day. They had first been welcomed and entertained with all hospitality by the Doliones, but in the evening, the same Doliones believed the landing crew were their enemies. Confusion on both sides led to a battle in which Jason and his men slew those who had earlier been their hosts. For three days the Argonauts mourned with funerary rites. The wife of the Dolione king hanged herself in grief. Then fierce tempests arose to keep the crew from sailing for twelve days and nights.

The prophet Mopsus interpreted the prophesying of a halcyon bird above the sleeping Jason, and so was able to instruct Jason in the offerings required to appease the deities for the atrocity that they had committed. Eventually favourable omens appeared, including the spontaneous gushing forth of a new stream from a rock. The storm ceased, and the Argo continued on its way.

Israel also had to contend with giants. The promised land was inhabited by them, and Joshua and Caleb attempted to exhort their people not to fear them. Sometimes a kings of Sihon or Og would come out to attempt to thwart the progress of the Israelites (Numbers 21), but under the leadership of Moses they always prevailed.

The best of intentions cannot avoid fate. The last people the Argonauts ever wished to slaughter were their hosts, the Doliones. Likewise Jephthah was trapped by the chance of his daughter being the first to see him after he had performed a vow, and he was thus compelled to slay her as a sacrifice. Mourning preceded this inevitable tragedy.

The Bible frequently narrates how Israel was held in check or defeated because of an unintended or unknown sin. The priests and sometimes prophets were on hand to direct the leaders to make the right sacrificial atonement.

Thy will be done

When against contrary tides the crew were too weary to continue rowing, Heracles alone kept the Argo in forward movement with his oar. But then his oar snapped in the middle, and soon afterwards they beached once again for the evening.

Ashore, the argonauts made friendship with the hospitable inhabitants of the land, and set about preparing for their evening meal and rest. Heracles went off to find a suitable piece tree from which to hew a new oar, while his young companion, Hylas, searched for fresh water. Heracles soon found what he was looking for and in with typical lack of subtlety pulled the tree from the ground, roots and all.

At the same time Hylas found water but a water nymph saw him first and lovingly embraced him dragging him down to his marital doom. His gurgling wedding scream caught the ears of Polythemus who went running after him, only to meet the returning Heracles. Both then went in search of Hylas fearing he had been kidnapped.

That was when favourable winds signaled the time for the Argo to set sail under Jason’s orders. Only once at sea did they realize they had left their companions back ashore. One of the crew, Telamon, expressed the feelings of all the others by berating Jason for not turning back immediately to recover their three abandoned comrades. It was not as if Jason did not care. He was, according to our translator, silently “eating his heart out” over those left behind. But silence can be taken for indifference and Telamon accused him of callously “Sitting there at your ease!”

The sea-god Glaucus intervened, fortunately, grabbed hold of the Argo’s keel to make sure everyone stopped to listen, and made it clear to all that everything was just as it should be: Zeus himself had decreed that Heracles was to go off and perform his famous twelve labours before dwelling with the immortals, Polyphemus was destined to found a great city, and Hylas was fated to be loved by a goddess.

It is not known at this point in the narrative, but Heracles’ being left behind will also turn out to be a means of the argonaut’s salvation in the future.

Telamon immediately sought Jason’s forgiveness for his rebuke, and Jason was perfectly understanding.

And this story explains the rites of the inhabitants who, to this very day, still enact the search for Hylas.

The same dramatic motifs fill the biblical stories. David is cursed by a hot-blooded scoundrel like Shimei (2 Samuel 16) who fail to appreciate that God’s will is being done, not David’s, that it is was no will of David that Saul should be slain. And David is big enough to let it pass, accepting the rebuke as part of God’s will also. (At least for the time being.) Peter and the disciples also rebuked Jesus a number of times, such as when he was planning on going to Jerusalem where danger waited for him, or when he failed to show care for them in the midst of a storm at sea.

The righteous and deserving are sometimes ordained for a different destiny by God, and that is part of the Bible’s theological message too, just as it is the same kind of message among the Greek poets. Moses cannot enter the promised land. The righteous, such as the likes of Enoch, are taken away to avoid the pains and torments of their companions, and to become immortal through other destinies instead, like Heracles.

Jesus is taken away from his companions, too, but it is for their salvation.

And the Old Testament narratives likewise have a quaint way of establishing the authenticity of their accounts by rounding off this and that scenario with a statement that account for this or that still to be found “to this day” — Jair of Manasseh named a place that is still called by the same name “to this day (Deut. 3:14); and Achan was buried beneath a mound of stones that can be still seen “to this day” (Joshua 7:26). Ah, the little tricks to add that touch of authenticity!

End of Book 1

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!