I have been recently addressing some common misconceptions about mythicist arguments. Another one is that “mythicism” places strained interpretations on passages that refer to Jesus as “the seed of David” and as being “born of a woman.” This post does not explore all the ins and outs of the arguments, but briefly points to what is overlooked by many of the historicist critics.

I have been recently addressing some common misconceptions about mythicist arguments. Another one is that “mythicism” places strained interpretations on passages that refer to Jesus as “the seed of David” and as being “born of a woman.” This post does not explore all the ins and outs of the arguments, but briefly points to what is overlooked by many of the historicist critics.

Other misconceptions I have recently addressed:

Mythicism’s alleged reliance on arguments from silence and too many assumptions:

/2010/08/16/doherty-the-sublunar-realm-and-paul-correcting-some-disinformation/

Mythicism’s alleged reliance on arguments for interpolations and metaphors (this includes a comment on the specifics of this post – seed of David and born of woman):

James the brother of the Lord:

/2010/05/02/applying-sound-historical-methodology-to-james-the-brother-of-the-lord/

and /2010/03/11/the-plot-driven-need-to-create-siblings-for-jesus/

Doherty’s sublunar realm discussions:

/2010/08/16/doherty-the-sublunar-realm-and-paul-correcting-some-disinformation/

So what about the “seed of David” and “born of woman” readings?

Mythicism per se does not hang on any particular reading of either of these passages in Romans and Galatians.

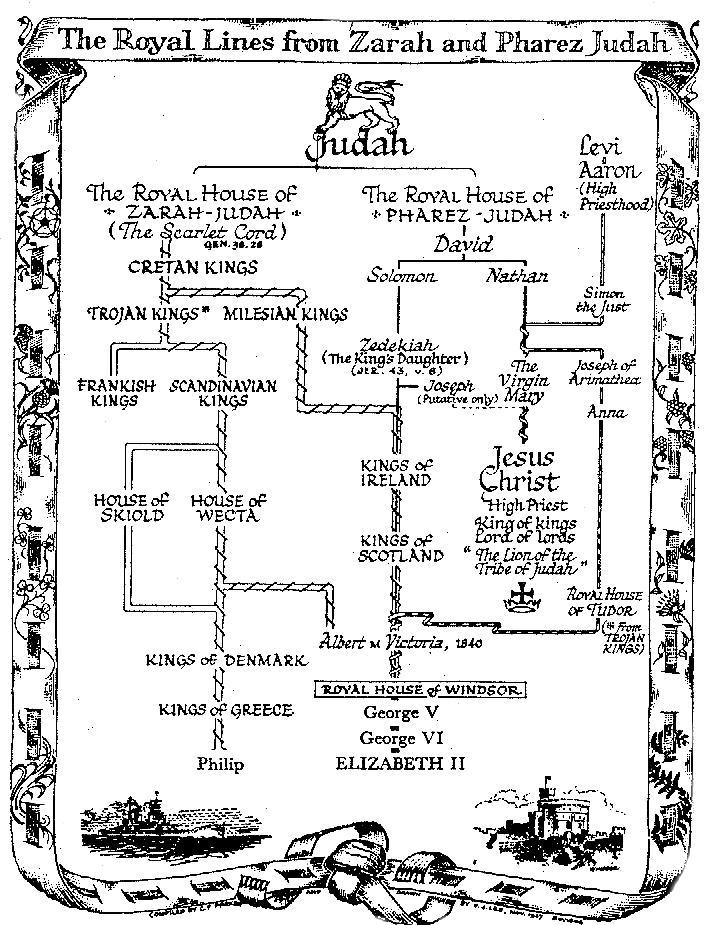

For example, there is nothing odd at all in the notion that a mythical character might be descended from a famed royal line or be born of a woman. Look at the mix of mythical and historical persons in the chart long cherished by British Israelites, for example.

It is worth keeping in mind that, in the light of recent scholarship and archaeological research, it is extremely unlikely that there ever was a “family of David” recognized as such throughout the Second Temple period. Major investment in institutional hedges would need to be maintained to guard its lineage in some identifiable sense if there were. Otherwise probably every Simon, Judah and Joseph in Palestine could have claimed a family tie to such an ancestor just as countless nobodies today across the continents can literally trace some family ties to the British Royal family.

As for the “born of woman” passage, it is unnecessary to single out examples of mythical characters who have been “born of women”.

My point here is not that this is what “mythicists” believe or argue in connection with these verses in Paul. It is to point out that the common default response of historicist critics does not rebut “mythicism” or establish the argument for the historicity of Jesus.

It is Doherty’s interpretation of these passages that has gained some prominence on the net, and I think many critics of mythicism have simply assumed that Doherty’s arguments are to be equated with “the mythicist” arguments — not that I have seen any evidence that these critics generally are aware of the nature of Doherty’s specific arguments.

Doherty’s argument is not “the mythicist” argument, but one of several arguments found among mythicists. In this respect, there is little difference from what we find among historical Jesus scholars who debate widely varying interpretations of the historical value of certain passages, their meanings, and conclusions to be drawn from them. Doherty examines the “seed of David” passage in comparison with similar phrases and terminology in Paul’s letters, and argues that it ought to be read as a mystical or spiritual meaning. One thinks of the way Kochba was presented as a Davidic Messiah, and the ambiguity of the Davidic references in Mark’s gospel, as well as the clearly spiritual meaning Paul invests in his “seed of Abraham” references.

But Doherty is not mythicism. He is one of a number of proponents of mythicism. One can disagree with Doherty’s interpretations, but that will no more dent the core case for mythicism than an argument against a Bultmannian interpretation of a Gospel passage will shake an argument for historicity.

So look at another well-known mythicist, one for whose arguments R. Joseph Hoffmann has expressed some measure of respect: G. A. Wells.

Here is what Wells has to say of the “seed of David” passage, with reference to the “born of woman” verse:

The earliest mention of Jesus’ Davidic descent is Paul’s statement (Rom. 1:3-4) that he is God’s son, “descended from David according to [i.e. in the sphere of] the flesh, and designated son of God in power according to the spirit of holiness [that is, in the sphere of the holy spirit] by his resurrection from the dead.” Paul, we recall, believed that Jesus had alway existed as son of God before coming to earth. Hence he is not here saying that Jesus was “designated” or “appointed” son of God only after his resurrection, but rather that he was designated son of God in power after that event . . . On earth he lived, according to Paul, obscurely and humbly, but after his resurrection was properly enthroned as God’s son. Thus his Davidic existence on earth was part of his act of humbling himself by assuming human form. Paul says that Jesus, “though he was in the form of God,” nevertheless “emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men” (Phil. 2:6-7). Thus “descended from David according to the flesh” of Rom. 1:3 is parallel to “born of a woman, born under the law” of Gal. 4:4, in that in both cases submission to something humiliating is implied.

Conservative scholars conjecture that Paul derived his information that Jesus was descended from David from the original community of Christians at Jerusalem, who, they believe, had known Jesus personally. But nothing that Paul says supports this. When he affirms Jesus’ Davidic descent, his intention is surely to state an article of faith on which both he and the Christian community at Rome which he is addressing (and which he never visited) are agreed. He must therefore have reckoned that his tenet was current there, and it is clear from his letter that — as one would in any case have expected — Christians at Rome about AD 60 were Gentiles or Diaspora Jews (in both cases Greek speaking). And so nothing in the evidence necessarily points to any connection with a Palestinian Jesus and Aramaic-speaking disciples. (The Historical Evidence for Jesus, p. 175)

So it is misguided of opponents of the mythical view of Jesus to dismiss the whole case primarily over disagreements with interpretations of a handful of arguments that they seem to deploy as simplistic proof-texts for the historicist position.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

‘Born of a woman’ is in Galatians 4, which talks about ‘the Jerusalem above’ and about allegorical meanings of children born to women.

Is it really such a stretch to claim that religious writers make up things to illustrate theological points even though they know they are not ‘real’?

I think you either misunderstand or underestimate the importance of the reading here. It might not be paramount to all muythicist readings, but for Doherty it is imperative that he is right here.

Remember it is not simply Doherty’s position that Jesus wasn’t real; it’s that Jesus wasn’t real and Paul knew it.

So it isn’t enough to suggest that mythical characters were given divine or royal parentage. It needs to be established that, while such myths developed, people knew full well they weren’t “real.”. And that such worldviews were widespread enough for Paul not to need to explain.

Some would have it that Doherty hasn’t adduced any evidence in favor of this at all. I’m not sure that I’d go that far, but it doesn’t matter. Certainly there are far more instances of “born of a woman” meaning born of a woman than there are it meaning born of a woman in a sublunar incarnation.

To recapitulate my main points:

1) It is imperative for Doherty that he is 100 percent correct. If he’s not then his entire reading of Paul is flatly contradicted by Paul himself.

2) While “strained” is perhaps not the best term, by the numbers the evidence is against Earl. That doesn’t mean he’s wrong, but it does mean that his reading can’t go much beyond the possibility that it’s a possibility. While his overall case might force the balance his way, if we are to deal exclusively with this issue, his reading is possible, but less supported.

I intentionally avoided the details of Doherty’s argument because I don’t see their relevance to mythicism per se. Mythicist arguments have been around prior to Doherty and exist independently of Doherty.

To dismiss mythicism because one disagrees with what one understands of the arguments of one mythicist is an indication one is not really interested in sincerely engaging the fundamentals that are largely shared by all.

(I’m not meaning here to express my own doubts about Doherty’s arguments. I have a different take again on the passages as I’ve indicated several times, but I have rarely seen anyone actually grappling with the details of Doherty’s case.)

Carr, concerning 2., thats nice but there is nothing about Paul’s use of figurative women in 4:21-31 that indicates that it is a figurative woman in mind at 4:4, unless to say that it shows Paul can use women in a figurative sense but who doubts that? Virtually any human being can use women in an allegorical way. Why should we believe that Paul means it allegorically at 4:4? Because it has to be if Paul doesn’t believe Christ had a human existence on this Earth? If I take born of a woman to mean that Jesus gestated in a womb before emerging from her uterus, I think I’m making a safe assumption based on the meanings of the words. It tells me the person wasn’t hatched from an egg or carved from stone.

Neil, so would it be fair to say that while you like Doherty’s theory of the action of Christ death and resurection taking place in a kind of spirit world, you don’t like his arguments from the Pauline epistles because you don’t share his assumption that they are Paul’s?

I find Doherty’s arguments plausible. Doherty’s arguments are not based, even in part, on this passage, by the way. Doherty, IIRC, seeks to explain why this passage is consistent / not inconsistent with his larger argument.

Three scholars who are specialists in the relevant fields are also on record as saying Doherty’s thesis is plausible and worth serious consideration. Three scholars who have strongly contradicted this view have, when I have asked them what they have read by Doherty himself on which they base their criticisms, equivocated (aggressively) or failed to reply at all.

As for the specific argument about David, I personally think that there are strong reasons for believing the passage to be a later insertion into Paul’s letter, and have based this view on my reading and application of one mainstream biblical scholar’s criteria to the specific points of another scholar’s arguments: http://vridar.info/xorigins/Romans/1_2-6.htm

This passage about David in Romans looks odd. The whole introduction looks strangely defensive and polemical in comparison with the tone of the rest of the letter. The reference to David does not fit anywhere else, or seem to have any relevance to anything else, in any of Paul’s letters. So I have personally seen little need to get too involved with Doherty’s arguments in relation to this passage. Doherty is much more conservative than I am with respect to interpolations.

Paul states that “Christ in you” is the hope of glory and that the the body of Christ is “the church.” Unless Jesus has two bodies his body is those who believe in him, according to Paul. In that sense, as the revelation of Christ from the scriptures, rather than historical events, is seen by Paul as the gospel, and because this revelation came first to those who were literally the seed of David, who collectively were the body of Christ, then Christ in that sense is of the seed of David.

Carrier makes a big deal out of Paul’s wording that Jesus was “made” out of the seed of David, not “born,” the same wording Paul uses for how Adam was formed. In response to that, I would say being “made” or “formed” simply indicates how the ancient Jews thought of conception. We see this understanding of “making” or “forming” in, for instance, Jeremiah 1:5, and Isaiah 49:5. And this agrees with Paul’s interpretation. Paul says “But who are you, O man, to talk back to God? Shall what is formed say to Him who formed it, “Why have you made me like this?” 21Does not the potter have the right to make from the same lump of clay one vessel for special occasions and another for common use?… (Romans 9: 20-21).”

Ehrman and many others have had a lot to say about the term, too. See Ehrman’s discussion quoted at https://vridar.org/2012/07/07/hoffmanns-mamzer-jesus-solution-to-pauls-born-of-a-woman/#EhrmanGal4

Also: https://vridar.org/2014/01/16/the-born-of-a-woman-galatians-44-index/ (and https://vridar.org/2018/01/15/the-function-of-the-term-born-of-a-woman/ )

I just read an article that said in some gnostic texts (I think Nag Hammadi) the Holy Spirit is referred to as the Holy Seed. I can’t see that this has been discussed at Vridar. Is it interesting or important and the Jesus mythology arguments?

Yes, “holy seed” is a different concept from the one we find in, say, the Gospel of John. I am currently attempting to bring myself up to date with gnostic studies, in particular with relation to gnostic origins. It may be some time before I get around to discussing anything in that area, though.