Robert Alter opens his book, The Art of Biblical Narrative (winner of the National Jewish Book Award for Jewish Thought), with a fascinating analysis of a small vignette that for most of us appears to interrupt the larger story of Joseph.

Robert Alter opens his book, The Art of Biblical Narrative (winner of the National Jewish Book Award for Jewish Thought), with a fascinating analysis of a small vignette that for most of us appears to interrupt the larger story of Joseph.

He takes the Hebrew texts of the Jewish bible and subjects them to the kind of critical analysis one might apply to Shakespeare or Proust. He tries to show, on the whole with success, that the astonishing literary effects often achieved by the Authors of the Bible are the results of art and not of artlessness. — J. M. Cameron, New York Review of Books, cover blurb.

So here we are, reading the book of Genesis and enjoying its familiar series of tales, and nearing the climactic final chapters we come to the story of Joseph. Joseph the young lad is given his famous coat of many colours; he’s then sold by his jealous brothers into slavery. But then just as we want to know what happens next we are diverted by a seedy chapter that has given us the word “onanism”. The chapter goes on to relate the patriarch Judah’s misdeeds, his daughter-in-law acting as a prostitute and the birth of his grandchildren. We then return to the Joseph drama with Joseph being taken to Egypt as a slave where he is purchased by Potiphar.

Why did the Genesis author break the Joseph story like that? (Or for those who are more discriminating with their sources, Why did the author of the J document break up the Joseph story like this?)

Robert Alter begins with the few verses preceding the Onan and Judah story. I have used much of Alter’s translation because he maintains the Hebrew word order and meanings that are significant for his argument.

Joseph’s brothers sold him into slavery then stained his tunic in goat’s blood to deceive their father.

32 They had the ornamented tunic, and they bring it to their father, and say, `This have we found; recognize, we pray thee, whether it [is] thy son‘s coat or not?’

33 And he recognized it, and saith, `My son’s tunic!

an evil beast hath devoured him;

torn — torn is Joseph!’34 And Jacob rendeth his raiment, and putteth sackcloth on his loins, and becometh a mourner for his son many days,

35 and all his sons and all his daughters rise to comfort him, and he refuseth to comfort himself, and saith, `For — I go down unto my son, to Sheol, mourning,’

and his father weepeth for him 36 and the Medanites sold him

unto Egypt, to Potiphar, a courtier of Pharaoh, his chief steward . . .

The phrases highlighted in bold are the focus of Alter’s argument.

The sons are the masters of subtlety in the way they lead Jacob to decide for himself what has happened to his son Joseph. Their lie is not direct, but takes the form of indirectly leading their father to come to the wrong conclusion himself. Their indirectness is matched by the author’s manner of narration: the narrator tells us they brought the cloak not to Jacob but to “their father” and asked him not of Joseph but of “his son”.

What does their lying for them is “this”, the object they hold before Jacob. The object, “this” [zot], is given the prominence in the exchange — going before them all as the leading prop and going first syntactically.

Jacob is asked to “recognize” [haker-na] it. This is a keyword that will tie together the themes of this and its bracketed story of Judah and Tamar. And Jacob did recognize [vayakirah] it. That act of recognition trapped him in the lie.

The narrator then has Jacob pronounce what he is certain has happened to his son in majestic verse (a perfect rhythmically parallelism in the Hebrew), not mundane prose.

Poetry is heightened speech, and the shift to formal verse suggests an element of self-dramatization in the way Jacob picks up the hint of his son’s supposed death and declaims it metrically before his familial audience. (p. 4)

The dramatization of his speech is matched by the overdramatic portrayal of his acts of mourning. His grief is expressed in as many as six separate acts:

- he tore his clothes

- he put sackcloth on his loins

- he mourned many days

- when his sons and daughters attempted to console him he refused to be consoled

- he wept, bewailed his son

- he proclaimed he would go down to his son in the underworld mourning

Jacob’s mourning is not only expressed in actions but in a series of small speeches, too. He declares his wish and will to mourn, and even “to go down to his son” in Sheol mourning. That turn of phrase also carries a weight of irony since as the story progresses we will find that Jacob does indeed “go down to his son”, but in Egypt.

To grasp how striking this depiction is we only have to compare two other mourning scenes just before and just after this one.

Before this scene, when Reuben (who had wanted to spare Joseph’s life) had returned to the pit expecting to find Joseph still trapped there, he expressed mourning for him by rending his garments. He then returned to his other brothers to discuss the situation.

29 And Reuben returneth unto the pit, and lo, Joseph is not in the pit, and he rendeth his garments,

30 and he returneth unto his brethren, and saith, `The lad is not, and I — whither am I going?’

We will see, by way of contrast, that Judah is not said to mourn for the deaths of his own sons, and his mourning for the death of his wife, is also depicted perfunctorily.

The extravagance with which Jacob’s mourning is depicted is finally underscored by the way the narrator shifts the scene back to Joseph. A literal translation captures best, Alter tells us, the irony of the seamless link between Jacob mourning Joseph while the Midianites are selling Joseph as a slave.

At about that time — moving to the story of Judah

At about that time Judah parted from [literally, “went down from“] his brothers and camped with an Adullamite named Hirah.

There Judah saw the daughter of a Canaanite named Shua, married her, and lay with her.

She conceived and bore a son, whom they named Er.

She conceived again and bore a son, whom she called Onan.

Then she bore still another son, whom she called Shelah; he was in Chezib when she bore him.

Judah got a wife for his firstborn, and her name was Tamar.

Er, Judah’s firstborn, displeased God, and God took his life.

Judah said to Onan: “Lie with your brother’s wife and fulfill your duty as a brother-in-law, providing seed for your brother.”

But Onan, knowing the seed would not be his, let it go to waste on the ground whenever he lay with his brother’s wife, in order not to give seed for his brother.

What he did displeased God and He took his life, too.

Then Judah said to Tamar his daughter in law, “Stay as a widow in your father’s house until Shelah my son grows up,” for he thought, “He, too, might die like his brothers.” And Tamar went off to dwell in her father’s house.

This new episode is tied to the preceding story with an ambiguous “at about that time” setting. Bizarre though this little story appears to be to modern readers, and with no apparent connection with the Joseph narrative, Alter shows that from the very opening it is indeed tightly linked to the larger surrounding narrative. (I have used Alter’s translation above.)

Going down

Judah “went down from” his brothers. He was separated from them, in other words, as has been the theme till now with Joseph separated from his brothers and father. The end of the story will see Jacob being “brought down” to Egypt. The same verb [hurad] is used. Compare also Jacob’s ironical insistence that he will “go down to” his son just before this scene.

So we open this narrative with the same theme of “going down”, or parting from the family.

Firstborn and reversals

There is also a common theme in the status of Joseph and Judah. Joseph is the first of the youngest of the sons of Jacob, and despite his “youngest” status, is destined to rule over all his brothers in his own lifetime. Judah is the eldest of Jacob’s sons and it is his destiny to father the line that will rule over Israel when the tribes become a kingdom.

With this in mind, recall one of the most persistent themes throughout Genesis — the way the divine will overturns the natural order of the elder son being the primary heir to the father. God regularly reverses the natural order and will of the actors involved by raising the youngest to the first place.

So here the larger story of Joseph is broken by a smaller story of the eldest son, Judah.

While the first story concluded with Jacob mourning the death of his son, the new story opens with the bare and stark details of a father taking a woman, lying and conceiving with her, followed by the birth, then naming, of sons. Then with no other narrative filler, we come to the marriage of the first son and his ensuing death.

The familiar theme of the demise of the firstborn is woven into this new narrative, too. As Alter says, “the firstborn very often seem to be losers in Genesis by the very condition of their birth. Er is identified as the firstborn at the time of his death — almost as if being the firstborn was what necessitated his death in the eyes of God.

The briskness of this second narrative, with its passing over of any mention of Judah mourning for the deaths of his own sons, forces the reader to register quite different perceptions of Jacob and Judah.

The author knows how to elicit different views of his characters simply by placing bare narratives beside each other, as if they must inevitably comment on one another. Jacob’s excessive mourning is set against the apparent absence of feeling in Judah.

Judah is depicted not as mourning but as responding matter-of-factly with instructions to his next son and daughter-in-law.

Tamar’s thoughts and feelings are never revealed. Is this because she is silently submissive or simply an indicator that she has no legal or practical options?

Alter points to one hint in the narrative that does remind us of Judah’s wrongdoing here. He unnecessarily points out to us again that Tamar is Judah’s daughter-in-law. This may be a reminder to the reader of Judah’s legal obligation to her that he is evidently reluctant to fulfill.

A long time afterward

The next verse is introduced by a new time-marker and begins a new phase of the story, one that is drastically slowed down in time:

A long time afterward, Judah’s wife, the daughter of Shua, died; after being consoled, he went up toward Timnah to his sheepshearers, together with his friend Hirah the Adullamite.

This verse presents essential information for what follows. Tamar’s argument to come (and accusation against Judah) is justified by what we read here.

A “long time” has passed. Tamar has been left abandoned by Judah for “a long time”.

Judah, unlike his father Jacob, “is consoled”. Literally this means that the official period of mourning comes to an end.

Tamar can now understand that her father-in-law is in a state of sexual neediness. So she sets about her plan:

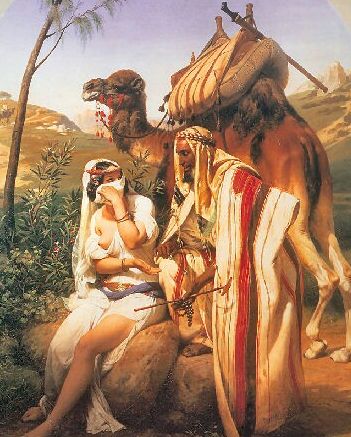

And Tamar was told, “Your father-in-law is coming to Timnah for the sheepshearing.”

Then she took off her widow’s garments, covered her face with a veil, wrapped herself up, and sat down at the entrance of Eynaim on the road to Timnah, for she saw that Shelah was grown up and she had not been given to him as a wife.

Judah saw her and took her for a harlot because she had covered her face.

So he turned aside to her by the road and said, “Look here, let me lie with you,” for he did not realize that she was his daughter-in-law. She answered, “What will you give me for lying with me?”

He replied, “I’ll send you a kid from my flock.” She said, “Only if you leave a pledge until you send it.”

And he said, “What pledge should I leave you”? She replied, “Your seal and cord, and the staff you carry.”

He gave them to her

and he lay with her

and she conceived by him.Then she got up, went away, took off her veil, and put on her widow’s garments.

Judah sent the kid by his friend the Adullamite to redeem the pledge from the woman, but he could not find her.

He inquired of the men of the place, “Where is the cult-prostitute, the one at Eynaim by the road?” and they answered, “There has been no cult prostitute here.”

So he went back to Judah and told him, “I couldn’t find her, and the men of the place even said, ‘There has been no cult prostitute here.'”

Judah said, “Let her keep the things, or we shall become a laughingstock. I did, after all, send her this kid, but you could not find her.”

Here we find Tamar, now sensing the injustice done to her, dramatically exploding from a tame, passive object, always “acted upon — or, alas, not acted upon — by Judah and his sons”, always the one who is forced into compliance and retreat, into “rapid, purposeful action, expressed in a detonating series of verbs”. She

- takes off

- covers

- wraps herself

- sits down at the strategic location

Then after her encounter with Judah she just as actively

- got up

- went away

- took off her veil

- put on her widow’s garments

Alter compares this quick series of actions with those of Rebekah who earlier was acting out a plan to deceive her husband, Isaac, into giving the primary blessing to her son Jacob.

Judah’s refusal to delay his sexual appetite leads him into the trap set by the one he had left to linger indefinitely unfulfilled, a childless widow.

The exchange is “wonderfully businesslike . . . reinforced in the Hebrew by the constant quick shifts from the literally repeated “he said” . . . to “she said” . . . .

Wasting no time with preliminaries, Judah immediately tells her, “Let me lie with you” (lit. “let me come to you,” or even, “let me enter you”), to which Tamar responds like a hard-headed businesswoman, finally extracting the rather serious pledge . . . a kind of Near Eastern equivalent of all a person’s major credit cards. (p. 9)

Tamar’s role is as the channel for the seed of Judah. So the keeps the reader hewed to relevant facts: Judah gave Tamar her price, so he was able to enter her, so she conceived.

When Judah sends his friend to redeem his pledge the one sought out is discreetly said to have been a “cult prostitute” [qedeshah] as opposed to a common whore [zonah]. (The former would not have been associated with the “base mercenary motives” of the latter.) The community correctly points out that no such woman has been there. The reader knows Tamar is far from being a qedeshah but a wronged woman seeking justice.

Climax

We now come to the climax of the story:

About three months later, Judah was told, “Tamar your daughter-in-law has played the harlot [zenunim].” And Judah said, “Take her out and let her be burned. [hotzi’uha vetisaref].

The naked unreflective brutality of Judah’s response to the seemingly incriminating news is even stronger in the original, where the synthetic character of biblical Hebrew reduces his deadly instructions to two words . . . (p. 9)

The same stark brevity (lost in the English translation) is continued . . .

As she was being taken out [vehi mutz’et], she sent word to her father-in-law, “By the man to whom these belong, by him am I with child.” And she added, “Please recognize [haker-na], to whom do these belong, this seal and cord and staff?”

Judah recognized [vayaker] them and he said, “She is more in the right than I for I did not give her to my son Shelah. And he had no carnal knowledge of her again.

The vignette concludes with Tamar giving birth to double her desire. Not one, but two sons (twins) are born to her. The one who appeared at first to be destined to be the last born suddenly “burst forth” to come out first. He was the ancestor of the line that led to King David.

If some readers may have been skeptical about the intentionality of the analogies I have proposed between the interpolation and the frame-story, such doubts should be laid to rest by the exact recurrence at the climax of Tamar’s story of the formula of recognition, haker-na and vayaker, used before with Jacob and his sons. The same verb, moreover, will play a crucial thematic role in the denouement of the Joseph story when he confronts his brothers in Egypt, he recognizing them, they failing to recognize him. (p. 10)

Alter drive his this point home:

This precise recurrence of the verb in identical forms at the ends of Genesis 37 and 38 respectively is manifestly the result not of some automatic mechanism of interpolating traditional materials but of careful splicing of sources by a brilliant literary artist. (p.10)

Of course (though Alter does not spell this out), simpler than “a careful splicing of sources” is a creative artist equally responsible for both the main and sub plots.

The pattern here relates a classic tale of the deceiver himself being deceived. Judah might be said to be the one primarily responsible for the selling of Joseph and deception of his father, Jacob, since he had proposed selling Joseph rather than killing him. If we see him as the leader of the brothers in their plot to deceive their father, we can see him, as the representative of all the brothers, now being the one who is, quite justly, deceived in turn.

God’s will of election and who is to carry the seed is done despite human plans to the contrary.

In the most artful of contrivances, the narrator shows him exposed through the symbols of his legal self given in pledge for a kid . . . , as before Jacob had been tricked by the garment emblematic of his love for Joseph which had been dipped in the blood of a [kid] goat.

Finally, when we return from Judah to the Joseph story (Genesis 39), we move in pointed contrast from a tale of exposure through sexual incontinence to a tale of seeming defeat and ultimate triumph through sexual continence — Joseph and Potiphar’s wife.

Robert Alter proceeds to discuss the way Jewish scholars in early medieval/late antiquity also noted the remarkable parallelism of these words and accordingly played on them to develop esoteric theological midrashic explanations. Alter then goes on to discuss the way the author of the Hebrew text dwelt upon ambiguity and “indeterminacy” for the readers to work out their own understandings of the characters’ motives, character, and psychology.

I will conclude here with a quotation from Robert Alter’s book that I recently used in another post here:

It is a little astonishing that at this late date (his book was published in 1981) literary analysis of the Bible of the sort I have tried to illustrate here . . . is only in its infancy.

By literary analysis I mean the manifold varieties of minutely discriminating attention to the artful use of language, to the shifting play of ideas, conventions, tone, sound, imagery, syntax, narrative viewpoint, compositional units, and much else; the kind of disciplined attention, in other words, which through a whole spectrum of critical approaches has illuminated, for example, the poetry of Dante, the plays of Shakespeare, the novels of Tolstoy.

The general absence of such critical discourse on the Hebrew Bible is all the more perplexing when one recalls that the masterworks of Greek and Latin antiquity have in recent decades enjoyed an abundance of astute literary analysis, so that we have learned to perceive subtleties of lyric form in Theocritus as in Marvell, complexities of narrative strategy in Homer or Virgil as in Flaubert. (pp. 12-13)

In short, it is misguided to assume that the books we read in the Bible are necessarily unliterary attempts to crudely cut and paste, from a mess of disparate sources, some rough narrative idea. Once we are prepared to accept that proposition, we must open our minds to the possibility that the narrative content we read is also the product of a creative imagination.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Joseph was the first of the youngest of the sons, you say. Yes that is true, but the youngest son is Benjamin. I have seen it suggested, since house of Joseph could be used as a synonym for the people of the Kingdom of Israel (aka Samaria, aka Ephraim, aka BethOmri ) as opposed to Judah, that in an earlier version Joseph was the youngest and beloved son with Ephraim, Manesseh and Joseph as his sons. This would fit in with the meaning of Benjamin, son of my right hand i.e.southerner, as the most southern part of Israel. Judah was an entirely separate kingdom.

It fits with Philip Davies theory of how the remnant name Israel became applied to Judah, that this version of the Joseph novel was developed in the Benjamin region with a mild criticism of fictional David’s fictional ancestors.

Not the main point of your post which is entirely convincing.

Friedman (The Bible With Sources Revealed p.94 bottom) makes a similar observation. He also points out, how the story points both backward and forward: Using Joseph’s coat to deceive Jacob is payback for the time when Jacob cheated his own father, Isaac, at his deathbed:

Here’s a good video of Robert Alter talking about some of these issues:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZSQqde4y-Vc

Brilliant, Thank you.