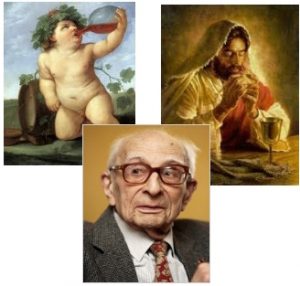

No, I am not going to argue that Christianity grew out of the worship of Dionysus or that the original idea of Jesus was based upon Dionysus. Rather, I am exploring the possibility that the portrayal of Jesus that we find in the Gospel of John is in significant measure a variant of the Greek Dionysus myth.

No, I am not going to argue that Christianity grew out of the worship of Dionysus or that the original idea of Jesus was based upon Dionysus. Rather, I am exploring the possibility that the portrayal of Jesus that we find in the Gospel of John is in significant measure a variant of the Greek Dionysus myth.

This possibility arises, I suspect, when we bring together the following:

- the insights of theologian Mark Stibbe into the way the Jesus story is told in the Gospel of John

- an understanding of the techniques used by ancient authors to imitate earlier literary masters (this goes well beyond Stibbe’s own contributions)

- the various ancient versions of the myth of Dionysus (this is preparatory to the fourth point . . . . )

- an anthropologist’s structural analysis of myths, in particular the methods of Claude Lévi-Strauss (this brings together key themes and information from the above three areas in a manner that strongly indicates the Jesus we read about in the Gospel of John is a Christian variant of the Dionysus myth.) — And yes, I will take into account the several works of Jonathan Z. Smith supposedly overturning the possibility of such connections.

This should hardly be a particularly controversial suggestion. Most theologians agree that the Christ we read of in the Gospels is a myth. These posts are merely attempting to identify one source of one of those mythical portrayals.

Let’s look first at what Mark Stibbe (John as Storyteller: Narrative Criticism and the Fourth Gospel) tells us about the literary affinities between the Gospel of John and the Bacchae, a tragedy by Euripides. Though the Greek play was composed five centuries before the Gospel it nonetheless remained known and respected as a classic right through to the early centuries of the Roman imperial era. Moreover, we have evidence that as early as Origen (early third century) the Gospel was compared with the play. See Book 2, chapter 34 of Origen’s Against Celsus.

But Stibbe does not argue that the evangelist directly borrowed from the play. Despite the many resonances between the two he writes:

It is important to repeat at this stage that I have nowhere put forward the argument for a direct literary dependence of John upon Euripides. That, in fact, would be the simplest but the least likely solution. (p. 139)

It certainly would be the simplest solution. The reason Stibbe thinks it is the “least likely” option, however, is the fact of there being significant differences between the gospel and the play. What Stibbe has failed to understand, however, is that literary imitation in the era the Gospel was characterized by similarities and significant differences that generally served to set the new work apart on a new thematic level. The classic illustration of this is the way Virgil imitated Homer’s epics to create the Aeneid. The differences that are just as important as the similarities and that even establish the very reason for the imitation. But all of this is jumping ahead to the next post.

Let’s look for now at the similarities, similarities that according to Stibbe may well be explained simply by the evangelist’s general awareness of the “idea of tragedy” in his culture.

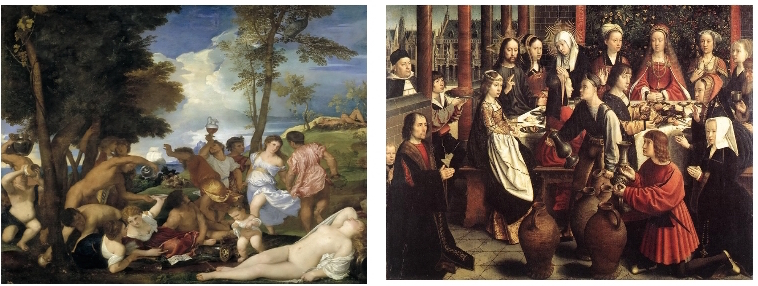

Water into Wine

It is often noted that Jesus’ miracle of turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana reminds us of the myth of Dionysus turning water into wine. Stibbe writes that such a miracle is entirely possible

Whether or not we agree with Fortna’s description of the wine miracle as legendary (it is, after all, possible that the miracle is historical and that the storyteller has given it a Dionysiac resonance) . . . . (p. 132)

and he has the support of the ancient naturalist Pliny the Elder who, on the authority of the consul, governor and respected author, Mucianus, assures us that a god was indeed responsible for performing such a miracle annually on the island of Andros:

In the island of Andros, at the temple of Father Bacchus [another name, from ‘grape’, for Dionysus], we are assured by Mucianus, who was thrice consul, that there is a spring, which, on the nones of January, always has the flavour of wine; it is called διὸς θεοδοσία (Gift of the God Zeus?) (Pliny the Elder, Book 2, chapter 106)

and

According to Mucianus, there is a fountain at Andros, consecrated to Father Liber [another name, meaning “free one”, for Dionysus], from which wine flows during the seven days appointed for the yearly festival of that god, the taste of which becomes like that of water the moment it is taken out of sight of the temple. (Pliny the Elder, Book 31, chapter 13)

This date was settled with the Julian calendar at 5th January and the arrival of wine from the subterranean spring was a form of the birth of the god of the vine.

But we leave this vignette aside for now to focus on something far more literary and comprehensive. This is where we begin to examine the first of the four types of study mentioned at the outset and that we will bring together to make a case that the Gospel of John’s Jesus is to a significant extent a variant of the myth of Dionysus. This first part — the insights of theologian Mark Stibbe into the way the Jesus story is told in the Gospel of John — will take two posts to complete.

Bacchae, the play

It is important to keep in mind that Euripides was adapting the myths into a tragic play and so inevitably created a version of the myth that was different and new in many respects. At this point I should ask all readers who have not yet read the play to do so before continuing. But easy-going softie that I am I will give everyone a Stibbe-Coles Notes summary instead. The following is largely an adaptation of Mark Stibbe’s own summary pages 132-134. But really, if you don’t know the play you will find reading it much more enjoyable than the following, and it’s not all that long. One online site is the Perseus Tufts page.

Prologue

Dionysus enters stage

He tells the audience that

he is the son of Zeus, the father of the gods;

he has come back to Thebes, the land where he was born;

he comes to his homeland unrecognized; though a god he is disguised as a man;

and though his father is the supreme god, his mother was a human, Semele, and her tomb lies outside the royal palace of Thebes;

Semele’s sisters are still alive and they are slandering their deceased sister, Dionysus’s mother, by saying that Zeus did not really father Dionysus — that is, that Dionysus is not divine at all and was born in disgrace;

Only Semele’s father, Cadmus, has continued to defend the name of Dionysus by honouring his daughter’s tomb;

Dionysus has come to avenge his and his mother’s reputation. He strikes Semele’s sisters with a frenzied madness — they go off to the hills to act out their ecstatic dances and rites of Dionysus (Bacchus);

That is just the beginning of his punishment upon the unbelievers. He next proceeds to reveal to mortals that he is indeed the son of Zeus by confronting the king, Pentheus, himself;

Dionysus informs us that the new king of Thebes is Pentheus, the grandson of Cadmus. Pentheus is an unbeliever and hostile towards the worship of Dionysus.

Pentheus enters

He criticizes the Dionysiac worship as an obscene scandal, and accuses Dionysus of being a ‘charlatan magician’.

He mocks Cadmus and the blind prophet Teiresias on seeing them in their Dionysiac costumes.

Teiresias rebukes Pentheus with a warning, telling him that Dionysus, son of Semele, is the supreme blessing of mankind because he is the inventor of wine that takes away the suffering of mankind. He gives the true medicine for misery.

Pentheus tells them they are mad.

Arrest of Dionysus

Pentheus arrests the effeminate stranger, the disguised Dionysus, who has “duped” the old men.

Dionysus accepts arrest. (Keep in mind that as far as the Thebans are aware Dionysus is an unknown stranger who has come to Thebes with a train of women devotees of the god Dionysus. They don’t know he is himself really Dionysus.)

He is brought before Pentheus.

In the ensuing exchange Dionysus responds to Pentheus’s interrogation with riddles, unexplained allusions, all amounting to mysterious or nonsensical answers as far as Pentheus is concerned.

Pentheus orders Dionysus to be bound in the darkest prison.

Dionysus breaks free

Great earthquake, the palace falls into ruins and the prison gates are opened.

Dionysus walks free, unhurt, from the jail.

Pentheus’ mother (Agave) in the Bacchic frenzies

Pentheus hears his mother and her sisters are engaged in Bacchic frenzy outside the city;

He decides to take out an army to rout the women;

Dionysus persuades him to secretly go out and spy on their proceedings;

To remain inconspicuous he persuades him to wear women’s clothes;

Once there, Dionysus helps him to the top of a tree for a better view.

Pentheus hoisted by the fir tree

Pentheus is helped to the top of the fir tree;

The women, led by Agave, see him, attempt to stone him from a distance;

They tear him to pieces, thinking they are tearing apart a lion.

The recognition scene

Agave returns to Thebes with the head of Pentheus, believing it to be the head of a lion;

Soon Agave and the women recover from their madness;

Agave recognizes she has killed her son;

Dionysus has thus inflicted severe penalties on them all for their unbelief and his divinity is reestablished among the Thebans.

Stibbe’s list of “very broad similarities” with John’s Gospel

We now get into some of the detail of Mark W. G. Stibbe’s observations we find in John as Storyteller.

- In both the play and the gospel the prologue introduces themes of a divine being going to his home but being rejected by his family and his own people;

- The protagonist is an unrecognized deity, a stranger from heaven, facing intense hostility and unbelief from the ruling elite of the city;

- The goal of each deity is to alleviate man’s sufferings, and this through wine or symbolic wine;

- The tragedy in both works lies in a failure to recognize a promised one who is really their own (Pentheus is actually a cousin of Dionysus — Cadmus was their grandfather);

- In both the final suffering (passion/pathos) consists of

- being dressed in humiliating garments;

- being led out of the city to a cursed hill;

- being hoisted on to a tree;

- and there killed.

- In both stories the women fulfill the role of the true worshipers of the visiting deity;

- The enemies attempt to stone each deity;

- “In both stories, the deity is ambiguous and elusive, often speaking and acting in such a way as to escape definition and capture.”

- Each story is set a city that was noted as the centre of institutionalized worship, and becomes infamous for its unbelief;

- Both Jesus and Dionysus have miraculous powers;

- The tragic action is not centred on one hero only: the Jews and Pilate are also major victims in the gospel, as are Pentheus, his mother and Cadmus in the play.

But the interesting devils are always in the details. They will be the study of the next post in this series.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Interesting, Neil. I also stumbled across this thread not long ago:

The Dionysus Connection

http://freethoughtnation.com/forums/viewtopic.php?p=26273#p26273

I hope any similarity between what I write and what you read on freethoughtnation will be purely coincidental. D. M. Murdock’s method is, from what I have been able to gather, to find as many parallels as possible (I note she studiously avoids that pejorative word in her comment, always using synonyms like common attributes or correlations) and throw them all together without much more ado.

As a result we find arguments that link concepts to be very shallow: e.g. the horns of Moses are said to be related somehow to the horns of Dionysus — but a little scratching of the surface and one finds that Moses’ horns are the result of a mistranslation in the Vulgate, so the idea that Moses had horns did not, evidently, arise until late antiquity.

Similarly, motifs that do not emerge in the evidence until centuries after the founding of Christianity are pulled back and read into the Gospels and associated with the very origins of Christianity itself.

I see Murdock also infers that her views about Moses and Dionysus have been rejected because scholars don’t know Greek. In reality, they have a lot more to do with the history of the “history of religions” school and the works of Jonathan Z. Smith.

I hope my own articles are a little more methodical and grounded than any of that. Not that I deny there are some very interesting connections between the Moses and Dionysus stories.

The most striking one the Bacchic devotees striking a rock with a sacred staff to bring forth flowing water. There is a similar motif among some Australian aboriginals. To understand that we need to take all the evidence into account, including what the aboriginal motif may contribute to the discussion, and that means informing ourselves more widely about literary relationships and evidence for when the various stories emerged, and not least to attempting an explanation of these relationships grounded in solid data and credible theory.

After following the above Freethought Nation link it appears that Acharya S has responded:

Moses and Dionysus with Horns

http://www.freethoughtnation.com/forums/viewtopic.php?p=27856#p27856

Her sources check out from where I stand. Any thoughts or corrections you’d like to make or, perhaps, an apology for the insults seems in order?

I have no interest in reading anything she has said over there. Is she saying I’ve insulted her again, is she? If you have any issues with what I’ve written in this post or if there is any error with what I’ve written in my comment then I would welcome it being pointed out here. Murdock or others are also welcome to do so — the only condition is that they refrain from personal abuse in doing so.

Let’s not forget Acts12.

And there’s something else—

those Bacchic women you locked up, the ones

you took in chains into the public prison—

they’ve all escaped. They’re gone—playing around

in some meadow, calling out to Bromius,

summoning their god. Chains fell off their feet,

just dropping on their own. Keys opened doors

not turned by human hands. .

(Translation copyright Prof. Ian Johnson. http://records.viu.ca/~johnstoi/euripides/euripides.htm

Here’s a Vridar-style comparison table.

Bacchae

Followers imprisoned by unbeliever

Followers chained

Chains fell of their feet

Prison doors opened by themselves

Followers escaped.

Acts 12

Follower (Peter) imprisoned by unbeliever

Follower chained Acts 12:6

Chains fell off Peter’s wrists. Acts 12:7

Prison door opened by itself Acts 12:10

Peter escaped Acts 12:11

No, this is out of place in this series and with the argument I am making. There are still other places in the Bible where an allusion to the Bacchae can be found or is likely, but that’s not what I’m working towards. We know the author of Acts drew upon a wide range of other literary influences, but what I’m addressing is a major influence in the making of the Christ depicted in the Gospel of John — and we will see that it goes beyond a set of allusions to a Greek play. This is just the beginning.

O.K.

I’ll wait to see where you are going wiht this.

(Though the influence of the Bacchae in other parts of the NT as well as in John leads me to suspect that the play – and perhap Dionysian religion – was a major influence in Early Christianity in general.)

Yet another source for the Jesus story. So far, we have Homer’s Odysseus, Julius caear, Vespasian, Titus, Asklepios, and Philo’s Logos. Either the gospel writers were brilliant or they were mad!

There are many threads from the wider religious-philosophical-literary culture that have been woven into the New Testament. I am specifically interested here in the adaptation of the Dionysus myth in the creation of the Jesus in the Gospel of John. This is a long way from suggesting Christianity or the Jesus story itself originated in the Dionysiac myth.

Very interesting these correspondences between the Gospel narrative and the work of Euripides.

But in John there is certainly an episode that is a close correlation between Jesus and Dionysus, that is the wedding at Cana.

I give my interpretation that is based on research of solar allegories in the Gospels (we’ve already talked about this as in “The Gospels were (and are) allegorical stories” https://www.academia.edu/4494891/The_Gospels_were_and_are_allegorical_stories ) and to this intuition does not escape some passes of John.

The miracle at the wedding of Cana can be interpreted as an allegory of the wine gift given to mankind by Jesus similar to what Dionysus and Bacchus did.

After meeting John the Baptist, where happends an exchange of roles (between John-Dying Sun and Jesus-Rising Sun), Jesus meets two disciples, Andrew and another not named (John 1,35-39).

They ask him where he lives, and Jesus takes them, and in that place, unspecified, they stop and hold.

John is at pains to tell us that’s, or it is almost, night if the tenth hour is understood as our four in the afternoon.

There is no other logical possible explanation of this step except into thinking that the night is approaching and they no longer have the time to go back.

The evangelist wants to tell us that the episode takes place at the winter solstice when we have the shortest day of the year, and shows us that Jesus house is where the sun sets.

If you add the days elapsed since the first encounter with John the Baptist, the canonical 25 december day of rebirth of the sun, to the wedding at Cana (Jn 2,1-11), they spend more or less seven days (you’ll notice that the evangelist count them one by one) and we are at the early January. If at Saint Martin, on November 11, you can taste the new wine, to drink good wine (“but you have kept the good wine until now,” said the master of the feast to the bridegroom) must wait the new year, is always this the case on thousands of years.

And this corresponds with the arrival of wine from the subterranean spring of Andros, or with the period in which the vinification perfects.

I fear that interpretations like these are another form of that error scholars who believe they can “see through” the text into events behind what is written. Many scholars seem to treat the text like a complex set of barriers that they must pull aside to see what lies beneath — that is, what “historical events” are there behind what is written. Is not an interpretation like the one you have given here doing the same sort of thing?

The problem is that we are losing sight of the text itself and treating it as a collection of discrete codes to be interpreted in terms of something outside the text. But if we attempt to understand the text as a whole and how it is all put together as a literary whole, then we are more likely to interpret the arrival at Jesus’ house at the tenth hour — where they “abide” with him — as pointers to the climactic events and words at the end of the gospel: Jesus is about to die and comforts his followers with a promise they will abide with him.

It is quite likely that there are allusions to the Dionysiac water to wine miracle, but if so, surely it is a more consistent explanation to see the evangelist declaring the superiority of the gift of the spiritual wine over the alcoholic “pagan” event.

If so, the message is the superiority of Christ to Dionysus and not their equivalence. As for the setting/rising sun images, I know of nothing in the text that suggests such links. Again this is a matter of looking through the text, using the text as a code for something else. (Again, this is the methodological error of scholars who use the texts as a “code” of sorts for historical events behind the scenes.) By examining the text in relation to other texts to which it clearly alludes we come to see that the two figures, the passing old and the rising new, have more to do with the transfer from the days of the Law and Prophets, Moses and the world, to the time of grace and truth — as set out in the prologue, the passage that sets the frame of reference for the rest of the narrative.

Yes these scholars, who believe they can “see through” the text, think, believe, that this text is a “code”, or better, an “allegory”.

“They have also writings of ancient men, who were the founders of their sect, and who left many monuments of the allegorical method. These they use as models, and imitate their principles”

For further details and source quotations on archetypes in the Dionysus mythos prior to the Common Era, (in particular, in rebuttal to statements by Gary Habermas during his infamous debate with Tim Callahan) see-

http://akhified.wordpress.com/2014/06/17/gary-habermas-on-dying-rising-gods/

The work of Dennis R. Macdonald, Jo-Ann Brant, George Mlakuzhyil and others surely put beyond reasonable doubt that the Fourth Gospel is a religious drama suitable for Greek theatre. It would make a good opera today.