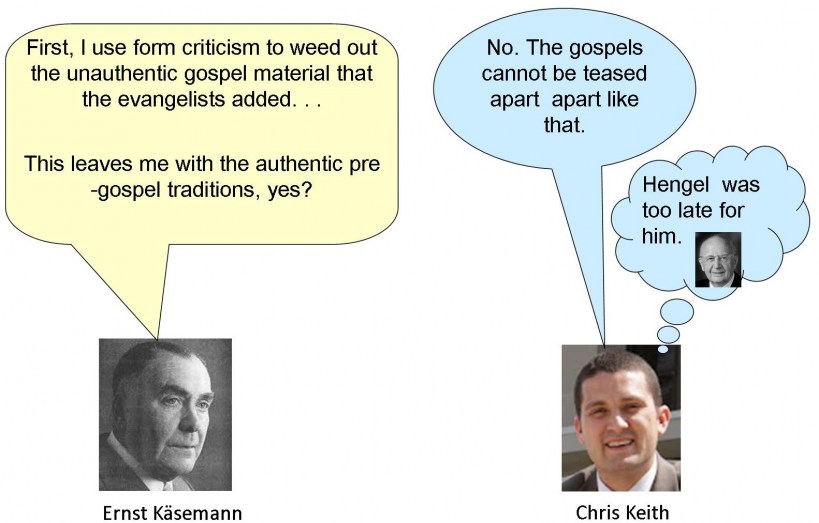

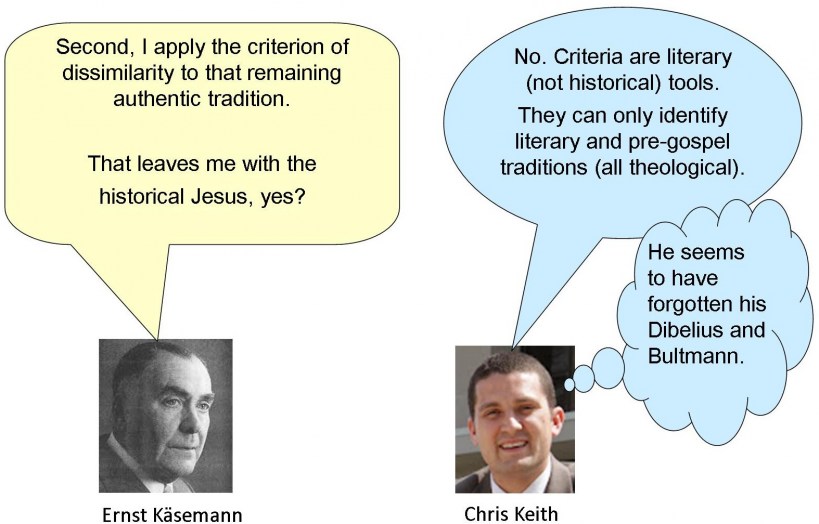

The above exchange is the message of Chris Keith’s opening chapter of Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity. My “idiot’s guide” is a tad unfair to Käsemann, however, since he did have willing accomplices and Keith mentions Norman Perrin and Reginald H. Fuller as guilty of formalizing more criteria of authenticity. The above may also be unfair to Morna D. Hooker whose arguments Chris Keith is supporting. But this post is about what I see as the good, the interesting and the missed opportunity in Keith’s chapter, so he gets the starring role above.

The above exchange is the message of Chris Keith’s opening chapter of Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity. My “idiot’s guide” is a tad unfair to Käsemann, however, since he did have willing accomplices and Keith mentions Norman Perrin and Reginald H. Fuller as guilty of formalizing more criteria of authenticity. The above may also be unfair to Morna D. Hooker whose arguments Chris Keith is supporting. But this post is about what I see as the good, the interesting and the missed opportunity in Keith’s chapter, so he gets the starring role above.

The title of this chapter is “The Indebtedness of the Criteria Approach to Form Criticism and Recent Attempts to Rehabilitate the Search for an Authentic Jesus”.

In the first part of this chapter Keith shows how the criteria used by historical Jesus scholars (criteria of embarrassment, of multiple attestation, of coherence, of dissimilarity, etc.)

- originated as a tool for form criticism;

- rely upon the discredited form-critical assumption that it is possible to distill pre-literary traditions from theological narratives of the Gospels;

- were designed to identify pre-gospel oral traditions, not actual history (or historical persons) behind those traditions.

After discussing this and briefly the second part of this chapter I will conclude with a return to Anthony Le Donne’s arguments for “triangulation” and “memory refraction”, this time with another critic’s more positive evaluation, than I raised in a recent post.

But before getting into the detail of the chapter here is my explanation of the “cartoon” above:

The form critics (led by Dibelius and Bultmann) worked on the assumption that the Gospels consisted of units of oral tradition that had been woven together into a literary narrative by later scribes of “the Church”. These gospel authors (evangelists) imposed their church’s theological interpretation upon their material as they stitched it together into our Gospels. The Gospel of Mark, being the first of the Gospels, is the primary target. (Matthew and Luke incorporated large chunks of Mark into their own accounts, again with modifications to serve their own theological leanings.)

Since these Synoptic Gospels are largely composed of pre-literary oral sources tied together this way, and mixed with other tales to fabricated by the Church or evangelists for their own purposes, it should be possible for the astute critic to analyse the Gospels and sift out what served Church interests from what did not. If a “life-setting” (Sitz im Leben) of the Church could be found for any Gospel material then that material was set aside in the ‘unauthentic’ pile. That was the evangelist’s fabrication. What was left over was, theoretically, the original oral tradition that had been extant before the Gospels were written.

But form-criticism pioneers Dibelius and Bultmann always understood that what was being unearthed (with the aid of “criteria”) was pre-Gospel tradition. This was the material picked up and used by the evangelists. There was no suggestion that this tradition relayed genuine historical fact.

But since Ernst Käsemann’s pivotal 1953 lecture that inaugurated the Second or New Quest for the historical Jesus initiated a new development. Henceforth ‘Questers’ would focus on that pile of Gospel material that had no Sitz im Leben in the Church responsible for those Gospels, and treat this as if it were potentially the original historical fact about Jesus. Form-critics had always understood they were dealing with traditions, literary or pre-literary. Never history per se.

In 1973 and 1974 Judaism and Hellenism by Martin Hengel was published in German and English and it effectively became clear to many that there was little discernible difference between Palestinian and Hellenistic Christianities. Other studies followed and the idea that the Gospels could be so neatly put through a sieve to separate Church-Hellenistic theology from pre-gospel “Palestinian” traditions was undermined.

Result:

The very foundations of form-criticism — that the Gospels could be analysed so as to separate late Hellenistic from pre-literary Palestinian Christianity — were undermined.

Criteria were applied by form-critics to identify literary strata according to the Sitz im Leben of the Church that produced them. They were never thought to be able to uncover “authentic history” behind any particular tradition.

But from the New/Second Quest for the Historical Jesus on, scholars took those form-critical tools of “criteria” and used them to supposedly identify genuine “historical” deeds and sayings of Jesus.

Since criteria appeared to have an objective ring to them, they were lapped up by scholars and treated as if they were truly scientific tools capable of uncovering real history.

Meanwhile: Morna Hooker’s warning that “real history” was not what they were designed to achieve went unheeded.

Scholars no longer take for granted the assumption that the Gospels can be neatly separated into theological Church/evangelist creations and pre-gospel/pre-theological oral traditions.

So form criticism falls to the ground and the tools of criteria must fall with it. Criteria cannot be salvaged by pretending they were designed to uncover something for which they never were designed (i.e. real history).

That, in sum, is the argument against using “criteria” to uncover a “historical Jesus”.

Now for the outline of the chapter:

Chris Keith opens at the point of Morna D. Hooker’s 1970 and 1972 publications that criticized the way “authenticity criteria” were being used in historical Jesus studies. (I recently discussed her 1972 article in a previous post as background reading for this post.) Keith’s “primary argument is that

Hooker is still correct — the criteria of authenticity, even in modified forms, simply cannot deliver what they are designed to deliver.” (p. 26)

Chris Keith shows us that even though “authenticity criteria” actually grew out of form-criticism, many scholars who have used these criteria simultaneously reject the methodological foundation from which they emerged. In other words, many have used these criteria for a purpose they were never meant to serve and even reject the original rationales for these criteria.

Why was Morna Hooker ignored?

Chris Keith comments:

From the perspective that hindsight enables, it is nothing short of amazing that the criteria approach to the historical Jesus managed to stagger out of the blow that Hooker dealt it in the early 1970s and attain such prominence in subsequent scholarship, particularly in the Third Quest for the historical Jesus where scholars as diverse as the Jesus Seminar and John P. Meier both affirm the criteria approach in one form of another. (pp. 26-27, my bolding here and in all quotations)

How could this happen? Keith suggests that the reason for criteria not only surviving but thriving was largely because scholars “overlooked or underappreciated” the fact that those criteria were directly born from, and justified by, form criticism — notwithstanding Hooker’s warning that this relationship with form criticism was their “primary problem”.

Many Jesus scholars simply forgot the origins of the criteria and without any reference to form criticism embarked on using them as if they were self-contained tools that could be used quite apart from their original purpose.

.

Unrealistic ambitions

Why were the criteria of authenticity detached from form criticism?

Chris Keith suggests two main reasons:

- In the New and Third Quests “criteria reached a quasi-canonical status” because they offered the appearance of “objective scientific common ground” among scholars of various beliefs.

In the excitement and effort to function like the hard sciences, then, scholars overlooked (or were simply unconcerned with) the criteria approach’s foundations. (p. 28)

- The criteria approach came to be seen as standing above and beyond any particular Quest. Theissen and Winter even traced elements of the criterion of dissimilarity back to Martin Luther in 1521. They came to be seen as neutral tools independent of use for any quest of any age for an historical Jesus.

The key point is that criteria of authenticity were detached from their rationale and came to be seen as a force in their own right without any reference to form criticism.

.

The irony

Morna Hooker wrote her critiques of the way authenticity criteria were being used at a time when form criticism dominated New Testament studies.

Today, however, most mainstream scholars have come to reject the foundations of classical form criticism as pioneered by Dibelius and Bultmann. But that hasn’t stopped them from using authenticity criteria that were crafted from the form-critical approach that they reject.

.

Form criticism gave birth to criteria

Chris Keith refers frequently to the various quests for the historical Jesus, in particular the New (or Second) Quest, the Third Quest and the period of No Quest. See the Wikipedia article for an outline of what each of these was. In brief:

- First Quest: Reimarus to Wrede, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

- No Quest: Schweitzer to Käsemann, first half of the twentieth century. (Bultmann)

- New/Second Quest: Began with a 1953 lecture by Käsemann

- Third Quest: Generally said to begin with the 1970s

Ernst Käsemann explained that form criticism was still “the only proper means of investigating Jesus.” Form criticism must first identify the Gospel material that can be identified as originating in a life-setting (Sitz im Leben) in the Church. This was the “unauthentic” material that was theological or narrative addition supplied by the Gospel author to meet the needs of the Church. He then applied criteria to the left-over “authentic” (pre-Gospel) traditions to discover the historical Jesus.

But Chris Keith says “no!” when Kasemann asks “yes?”

R. H. Fuller explicitly stated that he took the criterion of dissimilarity (“criterion of distinctiveness”) from Bultmann’s formulation for similitudes — thus being a prime example of a scholar who took form-criticism’s criterion for an oral tradition and applied it to a search for the historical Jesus.

Keith informs us that at this time it was taken for granted that scholars who used criteria of authenticity were also form critics or acknowledged their debt to form criticism.

Therefore, those who initiated the search for authentic Jesus tradition via criteria of authenticity, those who developed the criteria of authenticity further, and the peers of these scholars who assessed their work, all acknowledged that his approach to the historical Jesus is inherently dependent upon a form-critical methodological framework. (p. 31)

.

Use of criteria depends upon two assumptions

When a scholar applies criteria of authenticity he or she is assuming two things:

- that it is possible to separate the Gospels into two different types of traditions:

- one that reflects the traditions of the pre-Gospel past;

- another which reflects the Christian or early Church traditions that influenced the way the Gospel was written.

- that the above can be achieved “by identifying those traditions that reflect early Christian theological interpretation.”

Chris Keith will question these assumptions and conclude that distilling different traditions from the Gospels like this cannot be done. But first he looks at the historical background.

.

What form criticism is about

The separation of the written Gospels by means of identifying the interpretive work of later Christians is at the heart of form criticism. (p. 32)

So the form critic’s task is to separate the various strata in the Gospels. Some details belong to “the original historical tradition” and other strata belong to the author. How to separate these is the aim of form-criticism.

But why should there be a difference between the “original historical tradition” and the overlay from the author?

The form critic answers this by pointing to another assumption: that the gospels were composed by “Hellenistic Christians” who were removed from the original Palestinian Christians who were responsible for creating the earliest traditions about Jesus. The Palestinian Christians initially created oral traditions, not literary ones. It is these oral traditions that were taken by the later literary Christians and reshaped into written narratives expressing a particular theological point of view.

The form critic’s job was to break apart the units of early Jesus tradition from the theologically influenced narrative of the Gospels.

Once this was done the form critic would use these “free-standing units” to reconstruct the earlier oral tradition of the Palestinian church.

Keith stresses the importance of understanding that this is what form-criticism was about:

I underscore again, therefore, that separating the written Gospels into two groups — one belonging to the past behind the text and the other belonging to the present of the author responsible for the text — is at the very core of form criticism. (p. 33)

.

Form criticism becomes a historical tool

With the period of the New or Second Quest scholars began to use the same methods of form criticism to search for something different from that pre-Gospel oral tradition.

Form criticism was meant to discover the pre-literary oral tradition.

From the 1950s on scholars sought to discover something else: they sought to find the authentic Jesus traditions — the historical Jesus with the tools that had been designed to find the pre-Gospel tradition.

Now, form-criticism was to be used firstly to remove anything unauthentic — that is, anything whose Sitz im Leben could locate it as a product of the early Church.

The New Quest scholars sought the historical figure of Jesus rather than a prior state of the tradition found in the written Gospels, as had their predecessors. But they sought that historical figure with form criticism’s understanding of the nature and development of the gospel tradition — and thus form criticism’s methodology for recovering a past entity that predated the Gospels. (p. 33)

Käsemann made it clear. Form criticism’s role was to identify (and by implication invalidate) traditions anything in the Gospel that might be a late addition to the original sources:

Form Criticism is concerned with the Sitz im Leben of narrative forms and not with what we may call historical individuality. The only help it can give us here is that it can eliminate as unauthentic anything which may be ruled out of court because of its Sitz im Leben. (p. 33)

Käsemann himself noted that the new Quester turned his gaze from the Form Critic’s attention upon the “unauthentic” additions of the evangelist to that other pile of traditions — those supposedly “authentic”.

.

Spot that sleight of hand

Chris Keith writes:

New Quester scholars have simply substituted the historical Jesus for the pre-literary oral tradition. As one example, Bultmann advocated the criterion of dissimilarity for the recovery of similitude forms as they existed in the time of Jesus, that is, he sought a state of the oral tradition. Käsemann, Perrin, and Fuller left the logic of the criterion intact but instead sought the historical Jesus (via “authentic” tradition). (p. 34)

Compare Bultmann’s student Ernst Fuchs’ 1956 lecture, The Quest for the Historical Jesus:

For the question of the historical Jesus our first source can only be the Synoptic Gospels. New Testament scholarship today is generally agreed that these Gospels owe their form to kerygmatic considerations, and their matter subserves this form. The evangelists were not mere compilers of their material, but had what may be described as a theological plan. For example the author of the Gospel of Mark did not simply collect all the available material, but undoubtedly selected what his plan demanded (e.g. Mark 4.33). It is possible to separate the material from its framework. (pp. 34-45)

Fuchs’ thus also begins with form-critical assumptions but uses the criteria not for form-critical ends (to identify literary strata) but to uncover history itself.

Hooker spotted it

Precisely this usage of form-critical tools for historical ends caused Hooker to blow her whistle on the criteria approach. (p 34)

That returns us to my recent post on Morna D. Hooker’s 1972 article.

.

Chris Keith’s summary

In sum, therefore, the New Quest for the historical Jesus, which Käsemann initiated and others developed further, sought the historical figure of Jesus rather than the pre-literary stage of the Jesus tradition, as did form criticism. It borrowed its assumptions about how to recover that past entity from form criticism, however, as is clear in its explicit dependence upon a form-critical understanding of the nature of the Gospels. In particular, the criteria approach inherits from form criticism the assumption that scholars can and should separate the written tradition by extricating some Jesus traditions from the theology of later Christians such as the author of Mark’s Gospel. In this sense, the criteria of authenticity are little more than historiographical means of accomplishing the form critical task reflected in the following statement of Dibelius: “Since the evangelists merely framed and combined these materials, the tradition can be lifted without difficulty out of the text of the Gospels.” (pp. 35-36)

.

What does “Authentic” mean?

So just as the form critic believed it possible to extricate “authentic” pre-gospel oral traditions from the presumed later theological framework supplied by the evangelists, so historical Jesus scholars assumed it was possible to recover “authentic” historical Jesus material the same way.

“Authentic” is thus defined in the first instance in contradistinction to later Christian interpretation. . . . criteria of authenticity were designed upon, and assume, a definition of that word that amounts essentially to “does not reflect the theological interpretations of the Gospel authors and their communities.” (italics original)

.

Closer to core?

Not that all scholars were naïve enough to think that there is any tradition or memory that can be without any interpretation, but they did believe that there were nonetheless getting closer to “raw facts” and more reliable history by sifting through to “older layers”.

Conzelmann even spoke of “the core of the passion story” and tradition that passed the criterion of dissimilarity as “authentic . . . in the sense of historical fact.”

What was deemed to be a pre-Gospel source was essentially considered to be “Palestinian” and “lacking theological interpretation”.

This shift aided and enabled the perception of the criteria as objective scientific tools and reflects the criteria approach’s genesis in the Modern Era. (p. 37)

.

In the concluding post on this chapter I will cover why the form-critical assumptions that it is possible to prise apart various traditions — Hellenistic from Palestinian — in the Gospels, why it is fallacious to think that one can separate tradition from interpretation, and recent attempts to rehabilitate the criteria approach — including a return to Le Donne’s turn to memory theory.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Hi Neil, anthony here. Thanks for your very elaborate review! I realized that I hadn’t added your blog to our blogroll. This oversight has been corrected. Looking forward to more segments.

http://historicaljesusresearch.blogspot.com.au/

Hi Anthony, I am always worried when doing a review or summary presentation of a work that it is too easy to misrepresent or misunderstand something in the original. So don’t hesitate to point out any corrections or modifications as you see fit.

http://historicaljesusresearch.blogspot.com.au/2012/09/over-at-vridar.html

It seems to me that the Questers’ form-critical faces considerable danger of question-begging. As described in the post, it sounds as if they’re using a process something like this:

1) Assume there was an oral “Palestinian Jewish” proto-Christianity/Jesus movement.

2) Assume there was a later, written “Hellenized Diaspora/Gentile” proto-Christianity.

3) Go to the Gospel texts and use form criticism to sort out one from the other.

4) The “oral Palestinian Jewish material” thus identified is either authentic historical material or the closest we can get to such material.

In order to sort “oral Palestinian Jewish” proto-Christianity from “Hellenistic” proto-Christianity in the Gospels, we’d have to have a pretty good idea of what each would look like. How would we know that? If scholars start out assuming “oral Palestinian Jewish proto-Christianity” would look like X, then apply form criticism to sort out whatever parts of the Gospels look like X, then sure enough, the “oral Palestinian Jewish proto-Christianity” they identify would look like X! Furthermore, where do scholars get the idea of an oral Palestinian Jewish proto-Christianity in the first place? From the Gospel narratives, which portray the movement starting out with Jesus of Nazareth and his little group of peasant fishermen. Since peasant fishermen were very likely to have been illiterate, they must have passed down the words and deeds of Jesus as an oral tradition. But this assumes the very thing that historicists are trying to demonstrate: that there was a Palestinian Jewish proto-Christianity originating as an oral tradition from peasants organized around an historical Jesus.

How would we know if the “Palestinian Jewish” proto-Christianity, if there was one, was not itself Hellenistic in character? If it originated in Sepphoris or Caesarea, it could easily have been as “Hellenistic” as any proto-Christianity from Corinth or Antioch. The Gospels and the letters of Paul do seem to reveal a conflict in early Christianity over the question of observance of the Jewish law. Matthew’s Jesus upholds every jot and tittle of the Torah as valid “until all things are fulfilled,” whereas John’s Jesus is so estranged from it that he is portrayed several times using the formula “It is written in your law, X, but I say Y,” as if he is a Gentile and it is not his law as much as it is theirs. In Paul’s writings, especially Galatians, Paul argues against “Judaizers” who show up in his proto-Christian communities trying to impose Jewish observance.

The thing to note though, is that there does not seem to be any real argument in these earliest sources over the nature of Jesus himself. We do not see Paul arguing that Jesus was a divine, celestial being while harshly condemning the Judaizers for saying he was just a man they knew, a prophet, but not a Mystery Religion god-man. The Gospel writers sometimes portray Jesus appearing to deny divinity, but at other times accepting worship and claiming rights ostensibly belonging to God alone (e.g., the authority to forgive sins), and in gJohn, his pre-existent, universe-creating nature as the Divine Logos is stated explicitly. However they may disagree on details (such as at what point Jesus was proclaimed to be the Son of God), all portray him as a supernatural being. Whatever disputes may have existed, they were not sufficient to warrant whole discourses in the Gospels explaining Jesus’ nature and arguing against contrary ideas. Paul explains his concept of a heavenly Christ in considerable detail, but makes no arguments against or condemnations of a “Palestinian Jewish” concept of Jesus as a peasant prophet/shaman/social reformer. He claims to have “set forth” his gospel before James and the “Pillars,” yet the dispute that emerges is over circumcision and eating Kosher, not the nature of Jesus. So, if James was in fact kin to the historical Jesus, he apparently agreed with Paul that his brother created the Universe.

So, even though it is possible to identify a “pro-Torah observance” faction and an “anti-Torah observance” faction in the proto-Christianity of Paul’s era and that of the Gospel writers, there don’t seem to be pronounced “traditional Jewish” and “Hellenistic Mystery Religion” concepts of the nature of Jesus. How would we know which comes first: the Hellenistic chicken, or the Jewish egg? The Questers seem to just assume that a more traditional and orthodox “Palestinian Jewish oral tradition” came first, with Paul and the Hellenizers coming later. Apart from some kind of evidence for this prior to employing form criticism to sort out the “authentic” “Palestinian Jewish oral tradition” as the earliest layer, this is question-begging.

I think the absence of a major dispute over Jesus’ nature in the earliest writings comparable to the arguments over observance of Torah laws strongly implies that Paul’s heavenly god-man was not shocking to the “Jewish” (Palestinian or otherwise) branch of the proto-Christian community. This in turn implies that the “Jewish” branch was not traditional and orthodox, except when it came to observance of Torah regulations. Since they seem to accept a sophisticated Hellenistic conception of Jesus’ nature, they don’t appear to fit the picture of carriers of a conservative, rural Jewish oral tradition centered on a mortal man and his illiterate peasant disciples.

At the very least, we can’t just assume that such a tradition exists, and that it’s the earliest stratum of proto-Christian belief.

Spot on. Exactly. This blog has nothing more to offer you! 😉

Wouldn’t everyone be surprised if one day we learned that 1 Peter really were written by Peter and that he was literate after all and the fisherman portrayal was nothing but an allegorical type of the one who wrote the letter. Not being serious. Just musing on the nature of the house of cards that constitutes Jesus scholarship.

I agree about the question-begging, but I am not convinced that the dispute that arose in the mid-50s about Torah observance was unconnected with differing views about the nature of Christ.

Until the mid-50s “Paul” had been left pretty much to himself by the Jerusalem community. And we know that when his teaching did begin to be questioned, his Christ-doctrine had undergone some kind of change from what it was at an earlier point in time:

I think his abandonment of a kata sarka view of Christ could in turn have affected his view of Torah observance. Scholars generally hold that “Paul” must have, at least unconsciously, made some kind of distinction between the ritual or cultic or ceremonial part of the Torah and it moral part. The ritual part was abolished in Christ, but the moral part remained in force. But I find it strange that he never speaks explicitly of such a distinction in his letters. The distinction he does love to dwell on is between the pneumatic or spiritual and what is merely sarki, en sarki, or kata sarka .

So I suspect that the real Torah distinction that Paul had in mind was between its spiritual commands and the commands that involved material things. Foreskins were material, so, in his eyes, the command to clip them was a kata sarka command. And, as such, it could not have come from the highest God. It must have come from the lower stoicheia (“element spirits”). And that is why he viewed reception of circumcision by his Galatian flock not as submission to God, but as a return to bondage under the stoicheia. The element angels who made the material world enacted laws that involved material things. A Christ who is not kata sarka freed us from the spirit princes of this world and their kata sarka laws.

As you may have noticed, the above explanation is quite similar to what Simon of Samaria taught:

The decrees of the angels who made the material world (including the Jewish creator god) should be ignored. Their intent was to enslave men. One need only obey real laws, i.e., the ones that are spiritual and put in place by the Holy Spirit of God.

A distinction between spiritual commands and commands involving material things? Or a distinction between literal (worldly?) interpretation of commands rather than spiritual interpretation or allegorization? Thinking of his application of the command over not muzzling the ox being interpreted allegorically; circumcision being of the heart and not of the flesh . . . .

I think that during the earlier period of his Christian career—-and especially on the occasions he had reason to fear his teaching would be reported back to the Jerusalem pillars—-he did simply resort to allegorical interpretation of laws that dealt with material things. But at some point he crossed the line and assigned them squarely to the stoicheia. That turning point can still be detected in Second Corinthians and Galatians—even though the text we have of those letters has been tampered with. I expect that when, shortly afterwards, he went up to Jerusalem for the last time, the pillars confronted him with his crossing of the line, and he refused to back down. Henceforth Simon was an apostate and never again claimed that he and the pillars were on the same page. To him they were false apostles with a false Christ and a false gospel. And to them he was a blasphemer who had demoted the creator God of Israel and attacked His Law. By that blasphemy Simon earned the dubious distinction of being the first Christian heretic and the Father of Christian Gnosticism.

Fortunately for the survival of Christianity, a reconciliation of sorts did occur about seventy years later when a collection of some of Simon’s writings was reworked by the proto-orthodox and put out under the name “Paul”.

What was the title of Hooker’s article?

“On Using the Wrong Tool.” Theology 75 (1972): 570–81.