I expect this post will conclude my series challenging Richard Carrier’s arguments in On the Historicity of Jesus attempting to justify the common belief that early first century Judea was patchwork quilt of messianic movements. This belief has been challenged by specialist scholars* (see comment) especially since the 1990s but their work has still to make major inroads among many of the more conservative biblical scholars. We have seen the Christian doctrinal origins of this myth and I discuss another aspect of those doctrinal or ideological presumptions in this post. Carrier explicitly dismissed three names — Horsley, Freyne, Goodman — who are sceptical of the conventional wisdom, but I think this series of posts has shown that there are more than just three names in that camp. Many more than I have cited could also be quoted. Their arguments require serious engagement.

Richard Carrier sets out over forty social, political, religious and cultural background factors that anyone exploring the evidence for Christian origins should keep in mind. This is an excellent introduction to his argument, but there are a few I question. Here is one more:

(a) The pre-Christian book of Daniel was a key messianic text, laying out what would happen and when, partly inspiring much of the very messianic ferver of the age, which by the most obvious (but not originally intended) interpretation predicted the messiah’s arrival in the early first century, even (by some calculations) the very year of 30 ce.

(b) This text was popularly known and widely influential, and was known and regarded as scripture by the early Christians.

(Carrier 2014, p. 83, my formatting and bolding in all quotations)

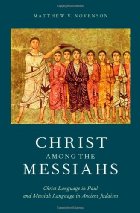

The current scholarly approach to the origins of Christology has been guided by the apocalyptic hypothesis. The apocalyptic hypothesis is that Jesus proclaimed the imminence of the kingdom of God, a reign or domain ultimately imaginable only in apocalyptic terms. Early Christians somehow associated Jesus himself with the kingdom of God he announced (thinking of him as the king of the kingdom) and thus proclaimed him to be the Messiah. If Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet, as the logic seems to have run, it was only natural for early Christians to conclude that he must have been the expected Messiah and that it was therefore right to call him the Christ.

With this hypothesis in place, the field of christological “background” studies has naturally been limited to the search for “messianic” figures in Jewish apocalyptic literature.2

…..

2. A theological pattern has guided a full scholarly quest for evidence of the Jewish “expectation” of “the Messiah” that Jesus “fulfilled.” Because of the apocalyptic hypothesis, privilege has been granted to Jewish apocalyptic literature as the natural context for expressing messianic expectations. The pattern of “promise and fulfillment” allows for discrepancies among “messianic” profiles without calling into question the notion of a fundamental correspondence. Only recently has the failure to establish a commonly held expectation of “the” Messiah led to a questioning of the apocalyptic hypothesis.

(Mack 2009, pp. 192-93)

Part (b) is certainly true. Part (a), no, not so. The apocalyptic book of Daniel was popular but it was not a key messianic text.

The book of Daniel was a well known apocalyptic work but most apocalyptic literature of the day contained no references to a messiah. Apocalypticism and messianism are not synonymous nor even always conjoined. Messiahs were not integral to the apocalyptic genre. It was more common in apocalyptic writings to declare that God himself would act directly, perhaps with the support of his angelic hosts. Very few such texts contain references to a messiah. Even when reading Daniel you need to be careful not to blink lest you miss his single reference to an anointed one (messiah). And even that sole reference, as we learn from the commentaries and to which Carrier himself alludes, is a historical reference to the high priest Onias III. There is nothing eschatological associated with his death.

Yes but, but ….

…. Didn’t the Jews in Jesus day believe that that reference was to a messiah who was soon to appear?

This is where a search through the evidence might yield an answer.

The evidence supporting “this fact”?

According to Carrier there is an abundance of evidence supporting “this fact” — by which he appears to mean both parts (a) and (b) in the above quotation.

This fact [i.e. a+b] is already attested by the many copies and commentaries on Daniel recovered from Qumran,45 46 but it’s evident also in the fact that the Jewish War itself may have been partly a product of it. As at Qumran, the key inspiring text was the messianic timetable described in the book of Daniel (in Dan. 9.23-27). (pp. 83-84) . . . .

. . . .

45. See Carrier, ‘Spiritual Body’, in Empty Tomb (ed. Price and Lowder), pp. 114-15, 132-47, 157, 212 (η. 166). The heavenly ascent narrative known to Ignatius, Irenaeus and Justin Martyr (see Chapter 8, §6) may have alluded to this passage in Zechariah, if this is what is intended by mentioning the lowly state of Jesus’ attire when he enters God’s heavenly court in Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 36.

46. On the numerous copies of Daniel among the Dead Sea Scrolls, including fragments of commentaries on it, see Peter Flint, ‘The Daniel Tradition at Qumran’, in Eschatology (ed. Evans and Flint), pp. 41-60, and F.F. Bruce, ‘The Book of Daniel and the Qumran Community’, in Neotestamentica et semitica; Studies in Honour of Matthew Black (ed. E. Earle Ellis and Max Wilcox; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. 1969). pp. 221-35.

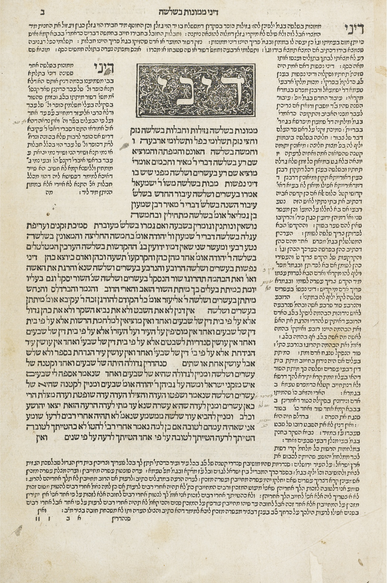

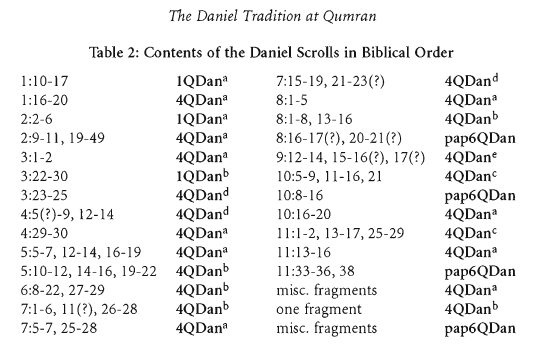

I suspect some oversight at #45 because I am unable to locate a related discussion in Empty Tomb. So on to #46. I don’t have Bruce’s book chapter but I do have Peter Flint’s. Here is his chart setting out the Daniel texts in the Qumran scrolls (p. 43):

Notice what’s missing, apart from any certainty regarding Daniel 9 as explained in the side-box. There is no Daniel 9:24-26. No reference to the anointed one. (We might see a flicker of hope with those few verses from chapter 9 in that table but sadly Flint has this to say about those:

Notice what’s missing, apart from any certainty regarding Daniel 9 as explained in the side-box. There is no Daniel 9:24-26. No reference to the anointed one. (We might see a flicker of hope with those few verses from chapter 9 in that table but sadly Flint has this to say about those:

However, the eighth manuscript, 4QDane, may have contained only part of Daniel, since it only preserves material from Daniel’s prayer in chapter 9. If this is the case — which is likely but impossible to prove — 4QDane would not qualify as a copy of the book of Daniel. (Flint 1997. p. 43)

But wait, it may not be lost, because another scroll, 11Q14 or the Melchizedek scroll, has a line that stops short where we would expect to find it, or at least a few words of it: Continue reading “Questioning Carrier: Was the Book of Daniel Really a “Key Messianic Text”?”