I conclude the series on From Adapa to Enoch with this post.

I conclude the series on From Adapa to Enoch with this post.

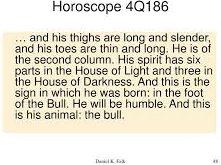

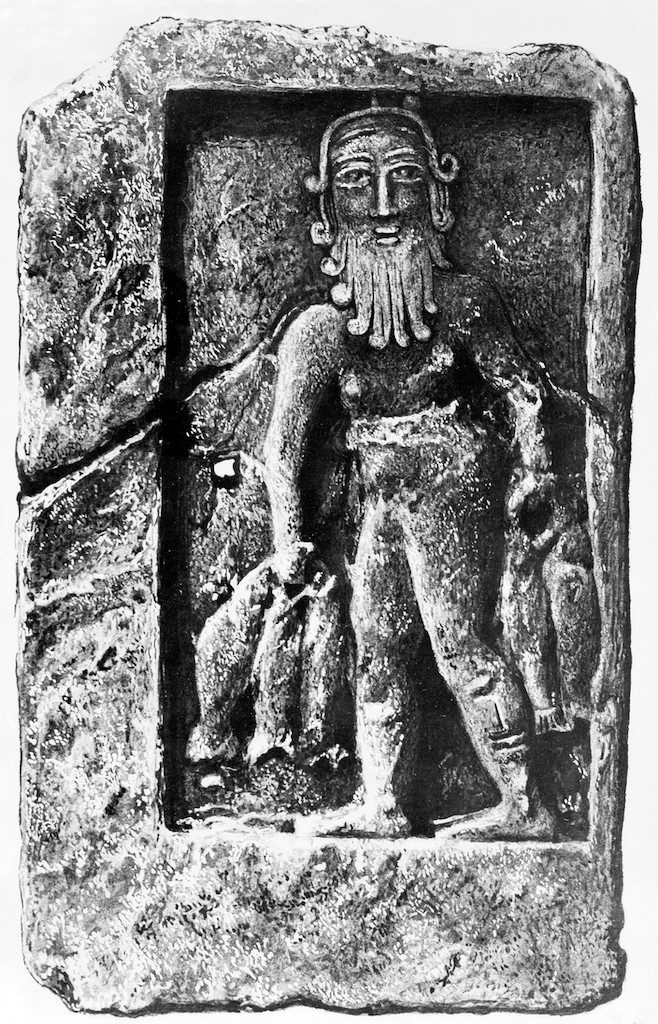

Ancient scribes were taught to see the world through the eyes of mythical heroes like Adapa and Enoch. They were taught to write in the voices of the likes of Adapa and Enoch. Through ritual mortals could even become the presence of those mythical figures. Even the early Christian writings declare the ability of human worshipers to bear the shining glory of God and sit with him in heavenly places. “Shining glory”, in that Mesopotamian-Persian-Hellenistic thought world was a corporeal entity that could be taken off and put on like clothing. We need to set aside our idea of dualism that posits an unbridgeable divide between the natural and supernatural realms. Dualism in the time we are discussing happened entirely within the realm of the single cosmos: the physical bore signs of the spiritual; a mortal could ascend into heaven and share in the divine glory and yet remain mortal. The entire universe was a system of signs. To be able to read the stars was to learn the language of the gods and to understand the secrets of the universe. A word had power to change the events in the physical world. The world was even created by words in the Judean myth.

Categories that are problematic for us to understand, like how a scribe could experience supernatural revelation or think that his words were of similar essence to preexisting revealed text, assume a radical distinction between the natural and the supernatural. But our Judean scribes, like Babylonian scribes, had no separate category for the merely material world as opposed to their culturally determined speech or God’s purely supernatural miracles. They had a semiotic ontology in which the universe was shaped by God in language-like ways. The … “reckoning, calculation” of speech can be implanted in the mind of the speaker of the [Thanksgiving Hymns], or God can cause him to perceive the [measurements] that govern the movement of sun and year. God organized essential pieces of human language in precisely the same way as he organized other mysteries and calculations of the universe.

(Sanders, 235. Highlighting and [] substitutions of technical expressions mine.)

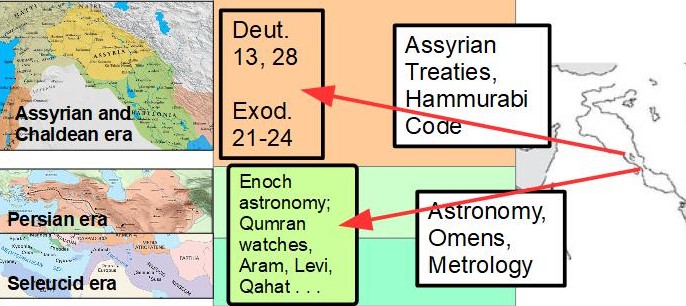

If this kind of knowledge had its origins in Mesopotamia, according to the thesis argued by Seth Sanders in From Adapa to Enoch, it found its way throughout the Near East, including Judea, in the “Parchment Period”, when new writing media (script, language, container) superseded clay and cuneiform. (We are talking fifth century B.C.E.)

Judean scribes made consistent changes to the Babylonian forms of knowledge that came their way:

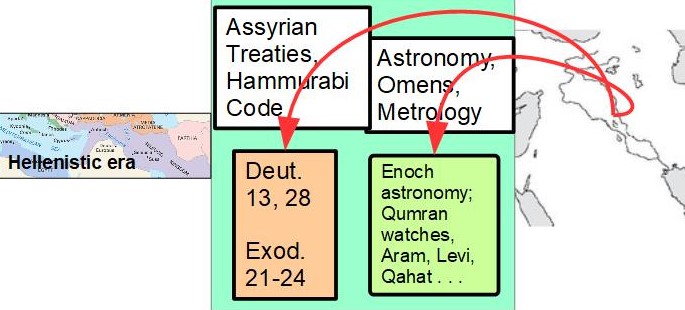

[I]n its adaption of Babylonian knowledge, Judea shows a pattern of narrativization. All known cases of Babylonian into Jewish literature involve a genre change into narratives of the ancient past. Whether ritual (the treaty-oaths of Esarhaddon), legal collection (the laws of Hammurapi), or astronomical and mathematical tables (Mul.Apin, Enüma Arm Enlil 14, the standard cuneiform fraction sequences), all were transformed into stories about ancestors, from Moses to Enoch to Levi. This reflects a dominant and widely recognized Judean literary value by which scribes conducted other major acts of text-building such as the Pentateuch (cf. Baden 2012, Sanders 2015, Schmid 2010).

(Sanders, 232 f. My highlighting)

To sidetrack for a moment into the Sanders 2015 citation above, Sanders sees the sources of the biblical narratives as being very the classical Mesopotamian literature. For example, the Genesis story of the Noah Flood appears to be based at least in part on a source like the Epic of Gilgamesh. Where the Genesis narrative differs from any Mesopotomanian narrative model is in its doublets (everything is narrated twice) and even in the fact that many of those doublets are inconsistent or contradictory. The possibility of a Greek influence never arises. A question in my mind relates to Greek historical narratives that do contain doublets with contradictions and other inconsistencies (see, e.g. Explaining (?) the Contradictory Genesis Accounts of the Creation of Adam and Eve). Other Greek literature even sets out a narrative structure that seems to foreshadow what we read in the larger story of the Flood and return to civilization through “Babel” (see, e.g. Plato and the Bible on the Origins of Civilization). Of course the narrator keeps himself in the background in the Primary History (Genesis to 2 Kings) so there is no personal intrusion to alert readers before introducing a second (and contradictory) version of events as we find in Herodotus. Questions remain.

Question 1: How does the above Mesopotamian/Near Eastern view of the conceptual unity of the material-cultural-supernatural worlds compare with Classical Greek and Hellenistic concepts? (Do we encounter evolution of ideas?)

Question 2: If the answer to Q1 points to differences then do we see these differences surface in the canonical and extra-canonical literature up through the Hellenistic and early Roman eras?

Question 3: Can we look more closely at the claimed extension of the above ideas to their early Christian analogs (e.g. Christians now sitting on thrones in heaven and reflecting more and more of the glory of God)?

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.