Along with his contradictory rationalizations to (1) declare the parallels between Jesus son of Ananias and the gospels’ Jesus to be “hopelessly flimsy”, yet at the same time are real and strong enough to (2) point to real-world parallel historical, socio-political, religious and onomastic events and situations anyway, Tim O’Neill further adds a common sophistical fallacy in a misguided effort to strengthen his argument:

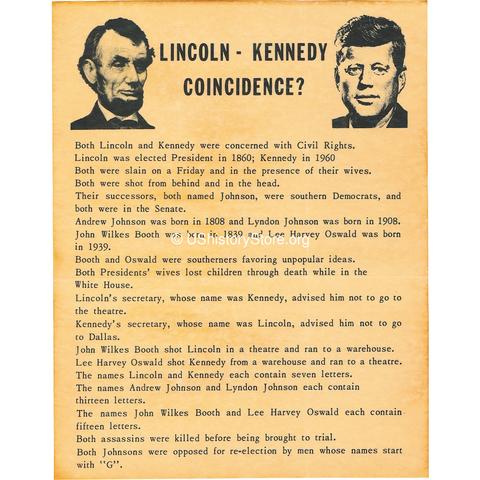

Even if we were to accept that the parallels here are stronger and more numerous than they are, parallels do not mean derivation. A far stronger set of parallels can be found in the notorious urban legend of the supposedly eerie parallels between Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lincoln%E2%80%93Kennedy_coincidences_urban_legend), but any future fringe theorist who concluded that, therefore, JFK’s story was derived from that of Lincoln would be laughably wrong. This is why professional scholars are always highly wary of arguments of derivation based on parallels. The danger is that if you go looking for parallels, you will find them. It is always more likely that any parallels that are not artefacts of the process can be better explained as consequences of similar people doing things in similar contexts rather than derivation of one story from the other.

Again O’Neill informs readers of what he seems to assume “professional scholars always” think and write. (Yet we will see that the fallacy of this analogy is the same as comparing apples and aardvarks.) Recall that Tim O’Neill is presumably attempting to inform his readers

of what is scholarly and credible and what is not.

Let’s see, then, how a scholar does respond to that same Lincoln-Kennedy parallel when it is laid on the table in the middle of a discussion about the two Jesuses parallels, son of Ananias in Josephus’s Jewish War and the Gospel of Mark’s Jesus. Brian Trafford posted to the Crosstalk2 discussion on 10th March 2003 the following (my bolding and formatting):

Brian TraffordMar 10 12:16 PM

I have a fundamental difficulty with attempts like this to read

meaning into parallels, especially when the possibility of mere

coincidence is dismissed too casually. For example, if one goes to

http://fsmat.at/~bkabelka/titanic/part2/chapter1.htm one can see a

number of parallels between the sinking of the fictitious ship Titan

in a book called _The Wreak of the Titan_ published in 1898, and the

real life sinking of the Titanic in 1912. In another article found

at http://www.worldofthestrange.com/wots/1999/1999-01-25-03.htm we

find a listing of some of the more astonishing parallels between the

assassination of Abraham Lincoln and that of John Kennedy. They

include:1. Lincoln was elected president in 1860. Exactly one hundred years

later, in 1960, Kennedy was elected president.

2. Both men were deeply involved in civil rights for Negroes.

3. Both me were assassinated on a Friday, in the presence of their

wives.

4. Each wife had lost a son while living at the White House.

5. Both men were killed by a bullet that entered the head from behind.

6. Lincoln was killed in Ford’s Theater. Kennedy met his death while

riding in a Lincoln convertible made by the Ford Motor Company.

7. Both men were succeeded by vice-presidents named Johnson who were

southern Democrats and former senators.

8. Andrew Johnson was born in 1808. Lyndon Johnson was born in 1908,

exactly one hundred years later.

9. The First name of Lincoln’s private secretary was John, the last

name of Kennedy’s private secretary was Lincoln.

10. John Wilkes Booth was born in 1839. Lee Harvey Oswald was born in

1939, one hundred years later.

11. Both assassins were Southerners who held extremist views.

12. Both assassins were murdered before they could be brought to

trail.

13. Booth shot Lincoln in a theater and fled to a barn. Oswald shot

14. Kennedy from a warehouse and fled to a theater.

15. Lincoln and Kennedy each have seven letters.

16. Andrew Johnson and Lyndon Johnson each has 13 letters.

17. John Wiles Booth and Lee Harvey Oswald each has 15 letters.

18. In addition, the first public proposal that Lincoln be the

Republican candidate for president (in a letter to Cincinnati

Gazette, Nov. 6, 1858) also endorsed a John Kennedy for vice

president (John P. Kennedy, formerly secretary of the Navy.)Obviously it would be easy, based upon this list, to conclude that

the story of Lincoln’s assassination served as the template used by

later creators of the story of Kennedy’s death.Very simply, if one takes two events and looks for potential

parallels, one can very often create a list that, on the surface

looks rather impressive, but on closer examination does not really

tell us very much. More importantly, it should make us cautious in

claiming that superficial similarities means that the earlier report

served as a template for creative fictionalizing by the later source

(in whichever direction one wishes to propose). I think that this is

the case with the parallels between the two Jesus’.https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/crosstalk2/conversations/messages/13026