Continuing from Part 3 of this series. . . .

In the previous post we noted the impact of modern historical studies on the traditional view of the Bible as the reliable foundation of Christianity. The problem posed by modern (beginning especially in the nineteenth century) historical methods was that they left large portions of the Bible irrelevant. If God revealed himself in historical events that were the foundation of biblical narratives, and if we could not recover what those historical events really were, then we had a problem.

If the best solution was for scholars to read into biblical accounts “traits and motivations derived from contemporary culture”, then one had to conclude “the impossible”, that the Bible’s religious significance derived in large measure not from the Bible itself but from modern minds! Theoretically there could be as many different interpretations as there were interpreters.

If scientific historical methods were to be applied to the Bible (as many scholars were beginning to apply them in particular to the Old Testament), one had to assume that God did not literally intervene in human affairs to change the course of events.

The only message of the Bible that was left for scholars to pass on was that God was “benevolently disposed” towards the human species,

but nothing more substantial than signals of paternal affection and filial trust and obedience can get through [the window between God and the world to the eye of faith]. (p. 74, quoting T. W. Manson).

The third solution

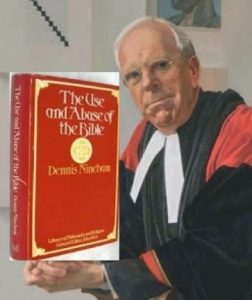

So Bible scholars were able to bypass the challenge of the natural sciences with relative ease and to meet the challenge of modern historical methods by withdrawing to the bare minimum of what was required of their God to maintain any presence at all among the faithful. But that latter retreat left many of the devout unsatisfied. So there was what Dennis Nineham calls a “third movement”: one that showed God was not just a distant image but a dynamic force in world affairs. This was

a movement back to the Bible which shows God actively doing things in the world to guide history and save men, and offers authoritative interpretations of his actions instead of leaving each man to be his own interpreter. This movement sought to give full weight to its observation that in the Bible historical statements and theological interpretation go closely together. The typical biblical statement, it was argued, is logically of the form: ‘Such and such an event occurred, and it constituted a divine intervention in this world by which God’s redemptive work was carried forward in such and such a respect.’ (p. 74, my bolded emphasis)

We begin with arguably the most influential theologian of the twentieth century, Karl Barth.

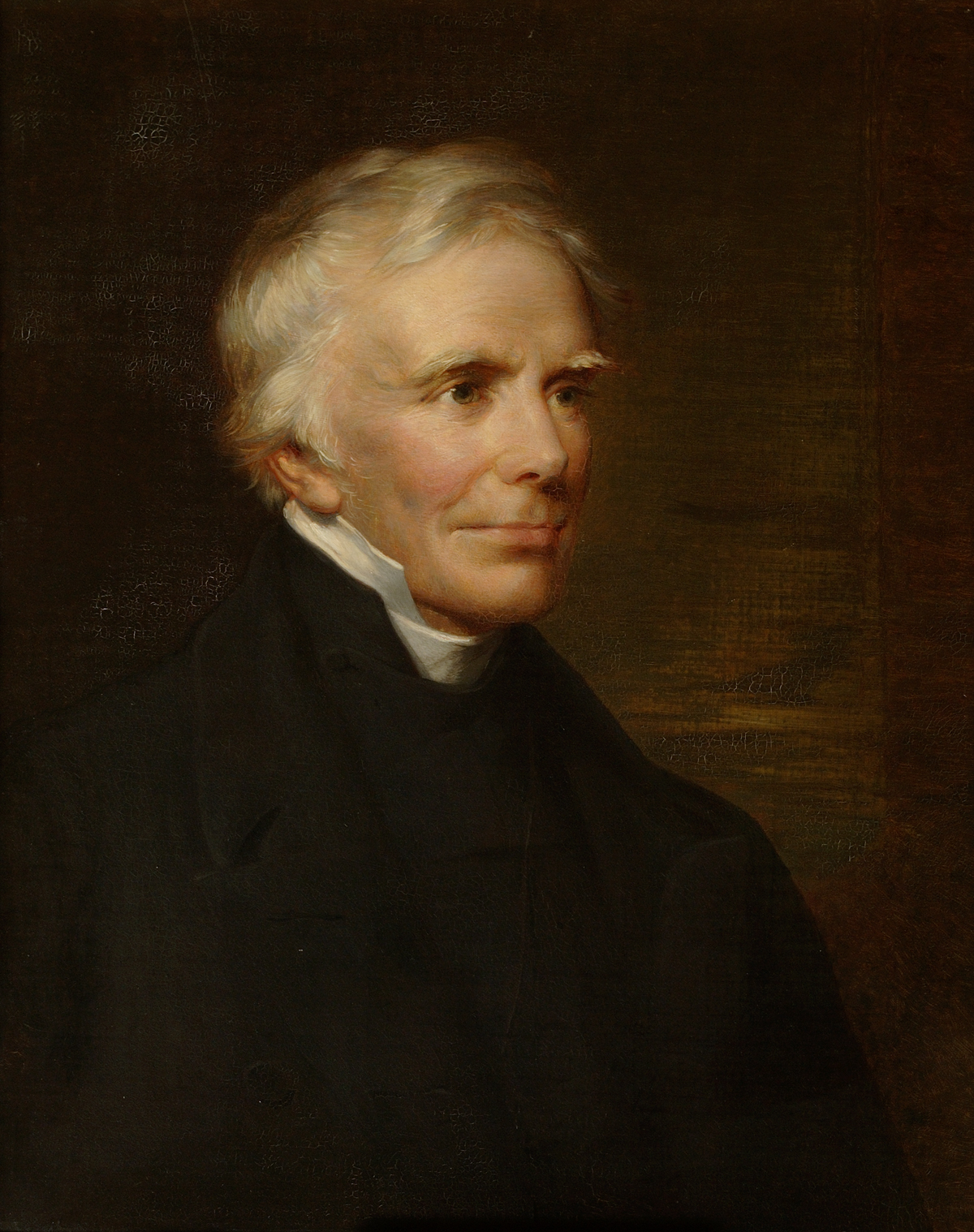

Karl Barth

Karl Barth attracted widespread support around the time of the first world war when he expressed dissatisfaction with the view that Bible scholars were, in Nineham’s words, in

unnecessary bondage . . . to the canons of historical study. And that study itself . . . was in bondage to the prejudice that the course of events is always completely uniform, that nothing ever happens for the first time and that nothing can be allowed as having happened in the past of a kind which is not experienced as happening in the present. (p. 75)

In other words, theologians had fallen into bondage to the godless view that the course of battles or public movements can be explained entirely as having human and natural causes.

But that’s not what the Bible says about historical events. If the message of the Bible were even only “partly true” — that God at least sometimes intervenes to disrupt the normal flow of human affairs — then historians were doing “a disastrous injustice to the biblical text.”

We now follow Dennis Nineham as he leads the discussion into a curious direction, yet one well-trodden by theologians. He infers that this secular view of how historians view the world derives from a singular and now outdated philosophical school of thought. This view of history, he suggests, can be traced back to Hegel, that is, to philosophical underpinnings that have long since been left behind. Accordingly, all reasonable scholars should, by rights, be fair and give serious consideration to the view that there is a God who intervenes in historical events.