Once or twice a year, Academia likes to email me a link to Anthony Le Donne’s page, highlighting the third chapter from his magnum opus. In that chapter, entitled “History and Memory,” he introduces us to Maurice Halbwachs and his “seriously deficient” La topographie legendaire des evangiles en terre sainte: Étude de memoire collective. I had once held out some hope that Le Donne would fix this chapter’s more obvious errors, such as calling Helena Constantine’s wife, but that’s never going to happen. So each time I read it, I sigh and shake my head.

The “Deficiencies”

In what ways, specifically, is La topographie lacking? Le Donne noted Halbwachs’s first deficiency was that “he relied heavily upon the account by the pilgrims [sic] of Bordeaux and neglected any part that Constantine played in the localization of holy sites.” It appears by his reference to “pilgrims,” Le Donne doesn’t understand that the first chapter of Halbwach’s book refers to a single Christian pilgrim who probably wrote this work in or soon after 333 CE.

The oldest testimony that we have of a traveler who went to Jerusalem on pilgrimage is a work called “The Account of the Pilgrim of Bordeaux.” We can place the exact date after the phrase: at Constantinople “albulavimus, Dalmatio et Zenophilo consulibus, d.III kal. Jun. Chalcædonia, etc.,” which is to say, 333 CE – 300 years after the passion and death of Christ, 263 years after the destruction of Jerusalem in by Titus, 198 years after the reconstruction of this city (Ælia Capitolina) by Hadrian. The voyage to Jerusalem by Helena, the mother of Constantine, occurred around 326 CE. (Halbwachs 1941, p. 11, my translation)

[translator’s note] Wess. 571, 6-8, “Item ambulavimus Dalmatico et Zenophilo cons. III. kal. Iun. a Calcedonia et reversi sumus Constantinopolim VII kal. Ian. cons. Suprascripto.” In the year 333, CE, these two men – Flavius Valerius Dalmatius and Marcus Aurelius Zenophilus – served joint consuls. See: Cuntz Otto and Gerhard Wirth. 1990. Itineraria Antonini Augusti et Burdigalense. Stuttgart: Teubner. See also: Stewart Aubrey and C. W Wilson. 1887. Itinerary from Bordeaux to Jerusalem [Itinerarium Burdigalense]: “The Bordeaux Pilgrim“; (333 A.D.)

Any fair reading of the text must recognize the heavy reliance on the pilgrim’s work. After all, it starts on page 11 and rambles on for 52 pages. Why did Halbwachs spend so much time referring to the pilgrim’s itinerary? He was forthright about his reasons for doing so.

Consider this text: how could we not take some time to study it? It is a unique remnant, closest to the period in which the events recounted in the gospels would have taken place, before which we find only a few texts in the writings of the early Church Fathers, but no continuous account from someone who witnessed the places. (Halbwachs 1941, p. 11, my translation)

He reminds us that the next instance we have of such an itinerary comes fifty years later with the Peregrinatio ad loca sancta by the Galician nun, Egeria (Ætheria).

Fifty years is a long time in a century where, after the construction of Constantine, many new traditions were quickly established. Moreover, in this second 60-page text, Ætheria’s journeys to Sinai, Mount Nebo, Mesopotamia and Cilicia – i.e. places mentioned only in the Old Testament – take up a significant part. Ætheria lived in Jerusalem for three years. She emphasizes ceremonies that take place on different days of the year around the Holy Sepulcher and Calvary, on Mount Zion, at Eleona, and on the Mount of Olives. She describes them meticulously and vividly; but there are only a few topographical indications. (Halbwachs, 1941, p. 12, my translation)

A Foundation

Notwithstanding this heavy reliance, a fair reading of the text must also acknowledge that Halbwachs does not rely solely upon our pilgrim, but quite often uses his work as a kind of baseline — a foundation upon which to compare other descriptions and analyses. Each successive account gives us a new perspective, but the pilgrim’s account is the first nearly complete itinerary of the sites — all the more valuable, because it describes the situation directly after Constantine and Helena made their marks on Palestine.

(I will note here that Halbwachs mentioned Constantine by name over 30 times, which I think you’ll agree is a rather unusual way to “neglect” the emperor. We’ll return to that theme later on.)

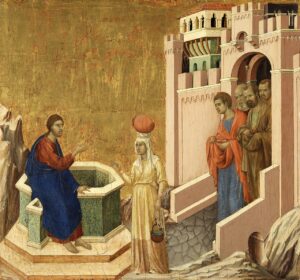

Remember, too that Halbwachs himself visited some of the same sites and had his own memorable experiences. Take, for example, Jacob’s Well (later believed to be place where Jesus met the Samaritan woman): Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 14: Halbwachs and the Pilgrim of Bordeaux”