Professor James McGrath explains in the Talk Gnosis video interview what he believes is “the case for the historical Jesus”.

Interestingly the interviewers open the program by assuring viewers that the interview with McGrath will provide loads of fun. To be discussed is a “fun topic” and “a super fun topic”. The point is to explain whether or not “there is a good reason to believe that Jesus actually existed”.

The prime interviewer opens by asking McGrath if the reason most scholars don’t believe Jesus is a myth is because they might think there are good reasons for thinking he is historical. Makes sense.

McGrath “personally” thinks a good case can be made for the historicity of Jesus.

Point one: When a mythicist apologist gets up and says that there is not as much evidence for Jesus as for an emperor who minted coins and fought battles then serious historians are not surprised.

Point two: Historians don’t bother discussing improbable miracles. What many mythicists lack is a detailed acquaintance with the New Testament texts and the rationalist (i.e. don’t believe in miracles) perspective that historians bring to them. Most mythicists are familiar with the Jesus they have been brought up with — i.e. that Jesus is God incarnate, etc. And so most mythicists are as shocked as conservative Christians are when you explain to them that Jesus as we meet him in the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of Luke is “not that sort of figure”. He is a human being in those gospels though people believed he carried out cures etc — just like other people in that day and even today who are believed to have those abilities.

So Jesus being believed to have these powers is just like other people also believed to have these powers whom we do think are historical.

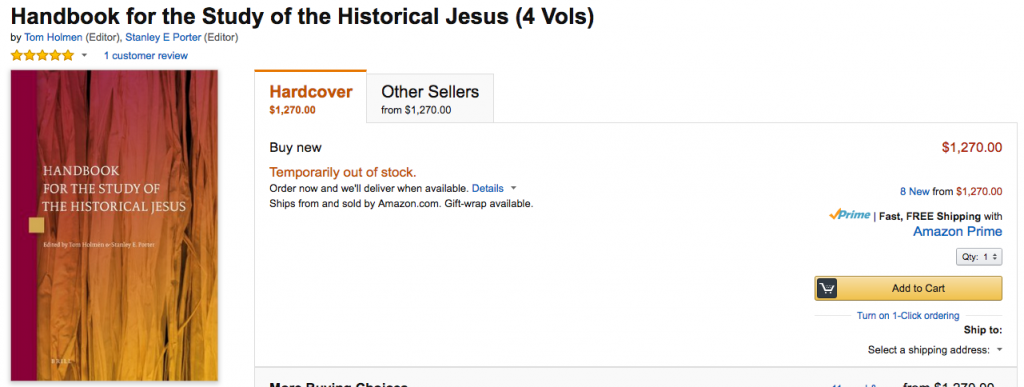

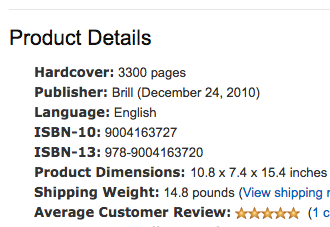

McGrath says mythicism is not a taboo topic but an outdated one. Casey and Ehrman took the time to look at recent claims and still found it to be unpersuasive. McGrath has “long wanted there to be some serious well-argued cases for this so it would give us something to discuss”. Scholars as part of their job description want things to discuss so if they don’t discuss mythicism it is because they think they’ll be hurting their own credibility if they do.

Next question: What are the reasons scholars believe there was a historical Jesus? Specifically, what are the reasons the crucifixion leads us to believe there was an HJ?

McGrath: No one would say that Socrates did not exist if the earliest evidence for Socrates came from a disciple of his. So it is bizarre to discount the evidence of early “Christians” for Jesus.

Paul says he met the “brother of Jesus (sic)”

Paul says Jesus was of the seed of David according to the flesh — thus indicating he believed him to be historical. Here Paul is talking specifically about “the Davidic anointed one” and referring to a “kingly figure” and the “expectation that the kingship would be restored to the dynasty of David”. That expectation meant that the messiah would be made the king, not crucified. So crucifixion was almost automatic disqualification from being the Davidic messiah.

“So if you’re inventing a religion from scratch and trying to convince Jews that this figure is the Davidical anointed one, then you don’t invent that he was crucified.”

Tony Sylvia (interviewer) adds that if you are inventing a story and wanted people to believe it you don’t include all the embarrassing things that don’t further your point. And crucifixion doesn’t help the early Christians’ case at all.

McGrath: It doesn’t give them the kind of figure they are claiming.

Mythicists often credulously swallow what historians find problematic. Example: mythicists often claim Jesus was based upon Old Testament prophecies as their fulfilment. It seems to McGrath that these mythicists have only heard this claim from Christian apologists or the NT authors themselves and that they haven’t actually looked carefully at these texts. In fact most of the scriptures are not prophecies at all and the few he seems to fulfil he doesn’t really (unless one forces the interpretation) so — if you’re inventing someone who fulfils the prophecies, you invent one who fulfils the prophecies. (Jesus doesn’t fit this bill.)

When we see the evangelists trying to link Jesus’ life with texts that don’t really fit him at all, then we have a situation where they have a real figure and they are struggling to make him fit — they can’t just make up anything about his life that they wanted to. Continue reading “Proofs that Jesus Did Exist (by Professor McGrath)”

Like this:

Like Loading...