Nanine Charbonnel casts a net back to catch an interesting observation by the nineteenth-century French Jewish scholar Joseph Salvador who wrote that since early Christian writings were in the tradition of Jewish writings they had to be interpreted in the same way as Jewish writings. That sounds mundane enough, but he went on to point out that Jewish literary figures like Adam, Israel, Esau clearly were constructed as personifications of humanity (Adam) and the peoples of Israel and Edom. The same for Abraham, Ishmael, Judah, Joseph, and so forth. (Their very names advertised that they were representations of collectives of people.) In the same way, Jesus was delineated to represent all of humanity, both “Jews and gentiles”. Jewish literary tradition was partial to the idea of a people rising up in vindicated glory after having suffered unjustly and cruelly at the hands of others. Indeed, who would not find such a myth appealing? From this perspective Jesus was read as a figure whom all peoples, in particular anyone or any collective who deeply felt a sense of unjust victimhood, could aspire to relate. The Jesus figure was likewise created as a representative figure, one whom all peoples could relate to in some significant way.

Nanine Charbonnel casts a net back to catch an interesting observation by the nineteenth-century French Jewish scholar Joseph Salvador who wrote that since early Christian writings were in the tradition of Jewish writings they had to be interpreted in the same way as Jewish writings. That sounds mundane enough, but he went on to point out that Jewish literary figures like Adam, Israel, Esau clearly were constructed as personifications of humanity (Adam) and the peoples of Israel and Edom. The same for Abraham, Ishmael, Judah, Joseph, and so forth. (Their very names advertised that they were representations of collectives of people.) In the same way, Jesus was delineated to represent all of humanity, both “Jews and gentiles”. Jewish literary tradition was partial to the idea of a people rising up in vindicated glory after having suffered unjustly and cruelly at the hands of others. Indeed, who would not find such a myth appealing? From this perspective Jesus was read as a figure whom all peoples, in particular anyone or any collective who deeply felt a sense of unjust victimhood, could aspire to relate. The Jesus figure was likewise created as a representative figure, one whom all peoples could relate to in some significant way.

Yet the literary artifice has led generations of readers to think of all of these characters as individual (and historical) persons. Such is the nature and power of their stories.

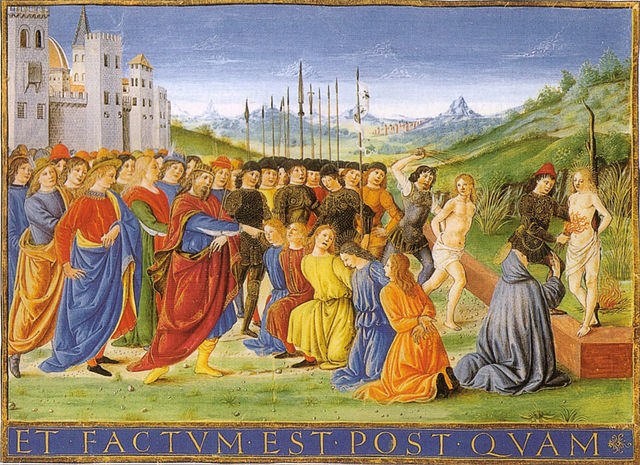

The Suffering Servant in Isaiah 53

We see a very early debate over this same principle in Origen’s third-century writings against the Jewish critic of Christianity, Celsus. Celsus, Origen complains, does indeed claim just what Joseph Salvador wrote, that the Jewish writings cleverly wrote of whole nations through a literary individual. NC quotes the entire chapter 55 of Book 1 of Contra Celsum:

Now I remember that, on one occasion, at a disputation held with certain Jews, who were reckoned wise men, I quoted these prophecies; to which my Jewish opponent replied, that these predictions bore reference to the whole people, regarded as one individual, and as being in a state of dispersion and suffering, in order that many proselytes might be gained, on account of the dispersion of the Jews among numerous heathen nations. And in this way he explained the words, Your form shall be of no reputation among men; and then, They to whom no message was sent respecting him shall see; and the expression, A man under suffering. Many arguments were employed on that occasion during the discussion to prove that these predictions regarding one particular person were not rightly applied by them to the whole nation. And I asked to what character the expression would be appropriate, This man bears our sins, and suffers pain on our behalf; and this, But He was wounded for our sins, and bruised for our iniquities; and to whom the expression properly belonged, By His stripes were we healed. For it is manifest that it is they who had been sinners, and had been healed by the Saviour’s sufferings (whether belonging to the Jewish nation or converts from the Gentiles), who use such language in the writings of the prophet who foresaw these events, and who, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, applied these words to a person. But we seemed to press them hardest with the expression, Because of the iniquities of My people was He led away unto death. For if the people, according to them, are the subject of the prophecy, how is the man said to be led away to death because of the iniquities of the people of God, unless he be a different person from that people of God? And who is this person save Jesus Christ, by whose stripes they who believe in Him are healed, when He had spoiled the principalities and powers (that were over us), and had made a show of them openly on His cross? At another time we may explain the several parts of the prophecy, leaving none of them unexamined. But these matters have been treated at greater length, necessarily as I think, on account of the language of the Jew, as quoted in the work of Celsus.

To which NC replies (translated):

Fascinating discussion, which only forgets that, if “there is no reason to apply to the whole people these prophecies which target a single individual”, it is because we ignore the full range of the text, of the speech, of the make-as-if rhetoric, not to mention the grammatical vagueness of the Hebrew language, which allows one to pass from the plural to the singular as it pleases as soon as one intends to refer to the collective. What may seem like a strong objection (how can the personification of the people be brought to death by the iniquities of the people?) is that the midrash mentality is not appreciated: without concern for contradiction, personifications can be those of different applications and aspects in the people.

We have an example in the Garden of Eden where God tells Adam (singular) that he can eat fruit from every tree in the garden but then switches to a plural form when issuing the command not to eat of the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

The flux between singular and collective and back again has been part of the interpretative apparatus of Jewish exegetes from the earliest days. With respect to the Suffering Servant passage in Isaiah 53 NC cites two scholars whose names are known to many of us, Daniel Boyarin and Charles Dodd.

Boyarin on Isaiah 53:

It has been generally assumed by modern folks that Jews have always given the passage a metaphorical reading, understanding the suffering servant to refer to the People of Israel, and that it was the Christians who changed and distorted its meaning to make it refer to Jesus. Quite to the contrary, we now know that many Jewish authorities, maybe even most, until nearly the modern period have read Isaiah 53 as being about the Messiah; until the last few centuries, the allegorical reading was a minority position. (152)

Dodd on the same and with an added note on the same singular-plural confusion with the Son of Man figure in Daniel:

In the New Testament there is only one place where the Servant is unambiguously identified with Israel, Lk. i. 54. Elsewhere, even passages in which the original distinctly equates the Servant with Israel are directly applied to Christ (e.g. xlix. 3). Yet there are evidences that the corporate, or representative, character of the Servant-figure is not entirely out of view. Thus xliv. 1-2, which most emphatically declares Israel to be the Servant, is echoed in passages of the New Testament where his attributes, “the beloved,” “the chosen” are given to Christ; yet the promise of water to the thirsty (verse 3) is confirmed not to Christ but to His people, as the Spirit, even in the original, is promised to the “seed” of the Servant, and as in xliii. 1-5, xliv. 21-24 the assurances “I have redeemed thee,” and “I am with thee,” are made to Israel, the Servant, and fulfilled to the Church.

There is a certain parallelism here with the treatment of the “Son of Man” figure, which is in Daniel vii declared to be a personification of “the people of the saints of the Most High,” but in the New Testament is applied as a title of Christ, yet frequently in contexts where the collective or corporate aspects of the figure are clearly in view. We shall be confronted with similar phenomena in our next group of scriptures, taken from the Psalter. (96)

NC does not continue with Dodd’s discussion of this phenomenon in the Psalms (she is discussing the Isaiah 53 verse, after all) but I will quote two sentences. On Psalm 69, a psalm quoted by Paul and all four evangelists, Dodd writes, Continue reading “How Collective Messianic Figures Mutated into Jesus — continuing Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier”